Blog Archives

Answering the Call of Remembrance Through Collecting

The line to get inside the Alamo is typically long but it does move quite fast. It is odd to see the city tower above the 18th Century structure.

There is no doubt that social media and news outlets will be dotted with posts and stories marking the 76th anniversary of the Day of Infamy – the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor and the surrounding military installations on the Island of Oahu – throughout this day. Though, I wonder if our nation’s youth are on the verge of forgetting about this event as we are losing sight of other terrible events that were perpetrated upon our citizens. Fortunately, forgetting about Pearl Harbor hasn’t quite happened yet as there are still WWII veterans, specifically Pearl Harbor Survivors remaining among us.

In the United States’ past history with such events, the meanings behind rallying cries such as “Remember the Alamo” and “Remember the Maine” are nearly lost to history. While visiting San Antonio this past summer, my family toured the Alamo and revisited the story of the siege and the ensuing battle that left no survivors among those who were defending the mission and fort. Without getting to far off track, the somberness of in the feeling one receives when walking through the building and the grounds is palpable but not the same as what is experienced when standing on the deck of the USS Arizona Memorial. Not too far from my home lies a monument – a memorial of sorts – from the USS Maine; the disaster that became the catalyst that propelled the United States into a war with Spain in 1898. This monument, a mere obelisk with naval gun shell mounted atop is easily overlooked by park visitors as it is situated a considerable distance from other attractions within the park. Remember the Maine?

- This monument to the USS Maine resides in Tacoma, Washington’s Point Defiance Park.

- The Point Defiance monument to the USS Maine was dedicated to the sailors of the Maine and to the Spanish American War veterans.

- The well-weathered granite base and projectile (from the Maine) is tucked away inside Point Defiance Park in Tacoma, Washington.

- This is one of five such monuments (from the Maine’s main battery) that are located throughout the United States. This is a 10-inch projectile that was removed from the raised wreckage of the ship.

The USS Arizona Memorial is situated on piers astride of the wreckage of the ship. The barbette of turret #3 is visible.

Visiting such locations always presents opportunities for me to learn something that I didn’t know before – details that one cannot grasp with the proper context that resides within the actual location of the event that took place there. Even though I had previously visited the Alamo (when I was very young), I had no memories of it and the entire experience was new and overwhelming. In contrast, the last visit that I made to the USS Arizona Memorial was my fourth (and the first with my wife) and I was still left with a new perspective and freshness of the pain and suffering that the men endured as their ships were under attack or while they awaited rescue (some for days) within the heavily damaged or destroyed ships. Unlike the Alamo, when one steps foot on the Arizona Memorial, they are standing above more than a structure that was once a warship of the United States. Beneath the waves and inside the rusting hulk are more than 1,100 remains of the nearly 1,200 men who were lost when the ship was destroyed.

Emerging from the waves are a pair of bollards from the starboard side of the forecastle of the wreckage of the USS Arizona, visible from the memorial.

This piece of the USS Arizona is on display at the Indiana Military Museum.

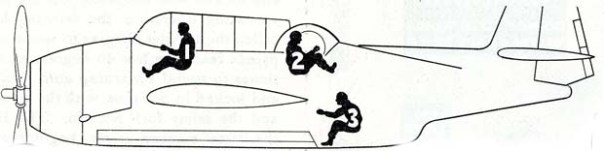

Interest in the USS Arizona (and the attack on Pearl Harbor in general) remains quite considerable for most historians. For militaria collectors, the passion to preserve the history of the ship and the men who perished or survived the ship’s destruction continues to increase. When any item (that can be directly associated with a sailor or marine who served aboard her) is listed at auction, bidding can happen at a feverish rate and the prices for even a simple uniform item can drive humble collectors (such as me) out of contention. Where the prices become near-frightening is when the items are personal decorations (specifically engraved Purple Heart Medals) from men who were killed in action aboard the ship on that fateful day. While any Pearl Harbor KIA grouping receives considerable attention from collectors, men from the Arizona are even more highly regarded. It is an odd phenomenon to observe the interest that is generated, especially when the transaction amounts are listed. While I certainly can understand the interest in possessing such an important piece of individual history, I am very uneasy when I see the monetized aspect of this part of my passion.

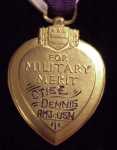

- When I see one of these posthumous Purple Heart Medals such as this one that was awarded to Seaman First Class Huys’ family, I cannot help but sense the pain of loss that was experienced by his parents when they first learned of the attack and that their son was among those who perished (image source: US Militaria Forum).

- Another posthumous Purple Heart Medal from an Arizona sailor, Radioman 3/c Otis Dennis (image source: US Militaria Forum).

- Electrician’s Mate second class Harold B. Wood’s Purple Heart and Good Conduct Medals. EM2/c Wood was killed aboard the USS Arizona on December 7th, 1941 (image source: US Militaria Forum).

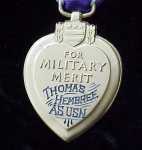

- Apprentice Seaman Thomas Hembree was awarded his Purple Heart Medal posthumously having lost his life aboard the USS Arizona during the Japanese attack (image source: US Militaria Forum).

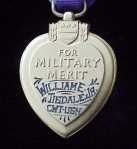

- Chief Watertender William Tisdale’s posthumous Purple Heart Medal (image source: US Militaria Forum).

Not wanting to focus on the financial aspects or my personal concerns regarding medals that are awarded to the surviving families, I have seen many collectors who painstakingly and beautifully research and preserve the personal stories of each sailor who was lost and for that individual’s specific medal. A handful of these collectors display these medals and personal stories with the general public which, I suppose can be likened to a traveling memorial to the service members who made the ultimate sacrifice. Without seeing such displays, it is very difficult to understand the magnitude of the personal sacrifices that are made by those who serve in the armed forces.

This group from a USS Arizona survivor contains the sailor’s photo album and distinguishing marks from his uniform (image source: US Militaria Forum).

Within my own collection are two photographs of the USS Arizona that were part of my uncle’s collection from when he served aboard three different battleships (Pennsylvania, Tennessee and California) during his navy career (from 1918-1929), all three ships that were later present when the Japanese attacked on December 7th, 1941. While I am certainly interested in the preservation of the history of this day, seeking Pearl Harbor or more specifically, USS Arizona pieces is not something that I am interested in with my militaria collecting. Instead, I spend time reflecting on what the service members within the ships, at the air bases and the citizens surrounding Oahu must have endured during the hours of the days, weeks, months and even years following the attacks.

One of two photos from my uncle’s navy photo album shows the USS Arizona transiting the Panama Canal.

Remember Pearl Harbor! Remember the Arizona!

For more on militaria mollecting of these significant events, see:

- A British Collector of the Alamo – Foreign Collectors of American Militaria

- Remembering (and Collecting) the USS Maine!

- A Piece of the Day of Infamy or Simply a Connection to an Historic Ship?

Consistency through Change – The U.S. Army Uniform

This uniform, though an immediate post-Civil War-issue, is clearly that of a sergeant in the U.S. Cavalry as noted by the gold chevrons (hand-tinted in the photo).

Over the weekend leading up to Independence Day, I had been inspired by my family military service research project, which had me neck-deep in the American Civil War, which caused me to drag out a few DVDs for the sheer joy of watching history portrayed on the screen. Since the Fourth of July was coming up, I wanted to be sure to view director Ronald Maxwell’s 1993 film Gettysburg, on or near the anniversary of the battle, which took place on July 1-3, 1863.

I had watched these films (including Gods and Generals and Glory) countless times in the past, but this weekend, I employed more scrutiny while looking at the uniforms and other details. Paying particular attention to the fabrics of the uniforms, I was observing the variations for the different functions (such as artillerymen, cavalrymen, and infantry) while noting how the field commanders could observe from vantage points where these regiments were positioned, making any needed adjustments to counter the opponents’ movements or alignments. For those commanders, visual observations from afar were imperative and the uniforms (and regimental colors/flags) were mandatory to facilitate good decision making.

The tactics employed for the majority of the Civil War were largely carryovers from previous conflicts and had not kept pace with the advancement of the weaponry. Armies were still arranged in battle lines facing off with the enemy at very close range (the blue of the Union and the gray of the Confederacy), before the commands were given to open fire with the rifles and side arms. The projectile technology and barrel rifling present in the almost all of the infantry firearms meant that a significantly higher percentage of the bullets would strike the targets. In prior conflicts where smooth-bore muskets and round-ball projectiles were the norm, hitting the target was met with far less success.

The uniforms of the Civil War had also seen some advancement as they departed from the highly stylized affairs of the Revolution to a more functional design. In the years following the war, uniform designs saw some minor alterations through the Indian Wars and into the Spanish American War. By World War I, concealment and camouflaging the troops started to become a consideration of military leadership. Gone were the colorful fabrics, exchanged for olive drab (OD) green. By World War II, camo patterns began to emerge in combat uniforms for the army and marines, though they wouldn’t be fully available for all combat uniforms until the late 1970s.

Though these uniforms have a classy appearance, they were designed for and used in combat. Their OD green color was the precursor to camouflage.

This World War II-era USMC combat uniform top was made between 1942 and 1944. Note the reversible camo pattern can be seen inside the collar (source: GIJive).

For collectors, these pattern camouflage combat uniforms are some of the most highly sought items due to their scarcity and aesthetics. The units who wore the camo in WWII through the Viet Nam War tended to be more elite or highly specialized as their function dictated even better concealment than was afforded with the OD uniforms worn by regular troops.

Fast-forward to the present-day armed forces, where camouflage is now commonplace among all branches. The Navy, in 2007-2008, was the last to employ camo, a combination of varying shades of blue, for their utility uniforms citing the concealment benefits (of shipboard dirt and grime) the pattern affords sailors. All of the services have adopted the digital or pixellated camo that is either a direct-use or derivative of the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) first employed (by the U.S.) with the Marine Corps when it debuted in 2002. Since then, collectors have been scouring the thrift and surplus shops, seeking to gather every digital camo uniform style along with like-patterned field gear and equipment.

The first of the U.S. Armed Forces to employ digital camouflage, the USMC was able to demonstrate successful concealment of their ranks in all combat theaters. Shown are the two variations, “Desert” on the left and “Woodland” on the right.

After a very limited testing cycle and what appeared to be a rush to get their own digital camo pattern, the U.S. Army rolled out their ACU or Army Combat Uniform with troops that were deploying to Iraq in 2005. With nearly $5 billion (yes, that is a “B”) in outfitting their troops with uniforms, the army brass announced this week that they are abandoning the ACU for a different pattern citing poor concealment performance and ineffectiveness across all combat environments. With the news of the change, the army has decided upon the replacement pattern, known as MultiCam, which has already been in use exclusively in the Afghanistan theater.

After a very limited testing cycle and what appeared to be a rush to get their own digital camo pattern, the U.S. Army rolled out their ACU or Army Combat Uniform with troops that were deploying to Iraq in 2005. With nearly $5 billion (yes, that is a “B”) in outfitting their troops with uniforms, the army brass announced this week that they are abandoning the ACU for a different pattern citing poor concealment performance and ineffectiveness across all combat environments. With the news of the change, the army has decided upon the replacement pattern, known as MultiCam, which has already been in use exclusively in the Afghanistan theater.

For collectors of MultiCam, this could be both a boon (making the items abundantly available) and a detractor (the limited pattern was more difficult to obtain which tended to drive the prices up with the significant demand). For those who pursue ACU, it could take decades for prices to start climbing which means that stockpiling these uniforms could be a waste of time and resources. Only time will tell.

Since the Civil War, the U.S. Army uniform has one very consistent aspect that soldiers and collectors alike can hang their hat upon…change.

A Bullet with No Name

Most people who know me would agree with the statement that I take pleasure in the obscurity and oddities in life. If there is any sort military or historic significance, my interest is only fueled further.

Militaria collectors have heard the same story told countless times by baffled and befuddled surviving family members – the lost history of an object that (obviously) held such considerable personal significance that a veteran would be compelled to keep the item in their inventory for decades. For one of my veteran relatives, that same story has played out with an item that was in among the decorations, insignia and other personal militaria, preserved for fifty-plus years.

The crimp ring around the middle of the bullet’s length shows where the top of the bullet casing was pressed against the projectile. When compared to these WWII .45cal rounds, it becomes apparent that the bullet is in the 7mm bore size-range.

When I received the box of items, I quickly inventoried each ribbon, uniform button, hat device and accouterments that dated from his World War I service through the Korean War. The one item that caught me by surprise was a long, slender lead projectile with a mushed tip.

They are difficult to make out with the naked eye, but the markings are “A-T-S” and “L-V-C”. The character in the center doesn’t appear to be a character at all.

It was clear that this blackened item was a small arms projectile. Based on size comparison with 9mm and 7.62 rounds, it was more along the lines of the latter, but it was clearly not a modern AK/SKS (or other Soviet-derivative). Perhaps it was a 7mm or smaller round? Without any means to accurately measure the bullet, I cannot accurately determine the bore-size or caliber. I’ll have to leave that for another day.

Further examination of the object proved to me that it was bullet that had been fired and had struck its target, causing the tip to blunt. While I am not a ballistics expert, I have seen the markings that firing makes on a bullet. This round clearly has striations that lead me to believe that it has traveled the length of a rifled barrel. It also possesses a crimping imprint, almost at the halfway-point on the projectile.

So what does all this information mean? Why did my uncle hang on to it for all those years? Had this been a bullet that struck him on the battlefield? Had it been a near miss?

In this view, the mushed tip is easily seen, as are some of the striations.

My uncle passed away 20 years ago and the story surrounding the bullet sadly died with him. Since he bothered to keep it, so will I along with other pieces in a display that honors several of my family members’ service.

Finding the “Lady Lex,” One Piece at a Time

A few weeks ago, our nation honored the 75th anniversary of the sneak attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7th. In the past few years, we have marked significant anniversaries of victories from WWII, the War of 1812 and this year we will begin recognizing the centennial of the U.S.entrance into the Great War. For collectors, these occasions spur us to evaluate our own collections while attempting to be discerning of sellers’ listings who are also trying to capitalize on the sudden interest.

In May of this year, 75 years will have elapsed since the first significant clash between the opposing naval forces of Japan and the United States in the Coral Sea. Leading up to this battle, the Navy had suffered losses in The Philippines, Wake Island and Guam followed by the sinking of the USS Houston (in the battle of Sunda Strait) all of which were leaving the U.S. extremely vulnerable and nearly incapable of mounting a naval offensive.

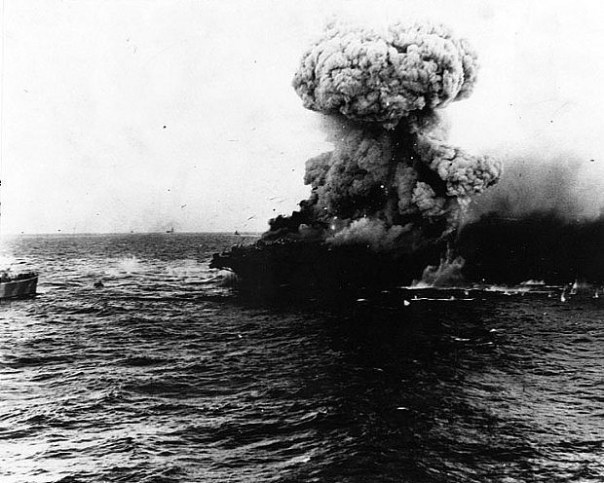

The Lady Lex is rocked by an enormous explosion during the Coral Sea battle, May 8, 1942 (Photo: Naval Historical Center).

USS Lexington (CV-2) provides electrical power to the City of Tacoma (WA) during a severe drought and subsequent electricity shortage – December 1929 – January 1930 (Photo: Tacoma Public Library).

Beginning with a joint effort between the US Army Air Force and the US Navy, the fight was taken to the Japanese home front with an B-25 air strike launched from the USS Hornet. But the direction of the war was seriously in doubt and Navy brass knew that inevitably, a direct naval engagement with the Japanese fleet were very near on the horizon.

Navy code-breakers had discovered the Imperial Japanese forces intended on taking Port Moresby in New Guinea and quickly dispatched Task Forces (TF) 11 and 17 to join up with TF 44 near the Solomon Islands and proceed West toward the Coral Sea. Over the course of May 3rd through 8th, the ensuing engagements between US and IJN forces resulted in substantial losses for both sides, including a carrier from each navy.

For the U.S. Navy, that carrier was the USS Lexington, CV-2. Though not the first purpose-built aircraft carrier (that distinction goes to the USS Ranger CV-4), Lexington was the first to be originally commissioned as a flat top. The Langley (CV-1) had a previous life as a collier, the USS Jupiter, for seven years from 1913 to 1920. The “Lady Lex”, as she would come to be known, laid down as a battle cruiser but was reconfigured during construction and was commissioned in 1927 as the US Navy’s second carrier, CV-2.

The result of the Coral Sea Battle was that the Navy was left with just two operational carrier: Hornet and Enterprise, as the Yorktown also suffered substantial damage in the battle requiring repairs. Less than a month later, the tables would be turned on Japan with the major American victory at Midway.

- A postal cover of the USS Lexington (Photo: Navsource.org).

- A leather squadron patch from the Early Knights of Bombing Two (VB-2) from the Lexington (photo: Brian’s WWII Surplus& Antiques Store)

- This SBD-2 Dauntless aircraft was recovered from a lake where it sat since 1945. While it was not a veteran of the Coral Sea battle, it did fly from the decks of the Lexington during the early months of 1942 (photo: National Naval Aviation Museum)

- This plotting board was used by Lieutenant (junior grade) Joseph Smith during the Battle of the Coral Sea when, while on a scouting mission from the carrier Lexington (CV 2), he spotted Japanese aircraft carriers and their escorts (photo: Naval Aviation Museum).

- A sailor’s leather-bound USS Lexington CV-2 Photo album (photo: eBay).

The loss was not only felt by her crew and navy strategists, but also by communities, such as Tacoma, Washington. For 31 days during winter drought conditions, the Lexington was sent to aid the city’s citizens by generating power ’round the clock, helping to keep their homes lit and warm. Many of those beneficiaries of the electrical power assistance were devastated by the news of her loss.

Today, few artifacts remain from the Lady Lex. Militaria collectors would be hard-pressed to obtain anything specific to the ship, instead having to settle for obtaining USS Lexington veterans’ personal effects or uniform items, surviving ephemera, philatelics, or vintage photographs. For many naval collectors, the hunt for anything from this historic ship can very rewarding. Some artifacts can be found by happenstance as was the case with this Curtiss SB2C Hell Diver, recently pulled from the Lower Otay Reservoir near San Diego, discovered by a fisherman who observed the plane’s outline on his fish-finder.

Armed with patience and time, collectors could assemble a nice group of artifacts to pay proper respect to the Lady Lex and the men who served aboard this historic ship.

UPDATE March 5, 2018: Paul Allen’s Undersea Exploration team that has been searching and discovering the wrecks of the Pacific War, finding such infamous sunken vessels as the USS Indianapolis and the lost ships from the Battle of Savo Island (USS Vincennes, Astoria and HMAS Canberra), announced today that they have located and filmed the wreck of the USS Lexington (CV-2) at the bottom of the Coral Sea in nearly two-miles of depth.