Category Archives: Trench Art

Researching After You Buy – Sometimes it is the Better Option

I’ve said it so many times in the past: it is paramount to making wise purchases that collectors research an item prior to handing over hard-earned finances to make a purchase. However, there are occasions within militaria collecting where the collector is stumped by what he or she might be looking at, yet still feel compelled to pull the trigger on a deal to acquire it.

Recently, a very dear friend and fellow collector presented me one of his most recent acquisitions and wanted to get my input as to the markings and what they might indicate. He was stumped by some of the heraldry and details but there were other engraved elements that showed the piece to be from World War I.

The dates of 1914, 15, 16 and 17 automatically rule out this matchbox as being a U.S. trench art piece.

I spent several minutes examining what appeared to be a trench art matchbox. Clearly, the item shown is constructed from brass and was handmade. The brass plates were rolled out and soldered together to form an oblong can-shape with another piece cut and soldered into place at the top. A piece of wood was shaped and fastened to comprise the case’s bottom, and adhered with some sort of clear glue or shellac. Judging from the length of the box, the brass was an unrolled and flattened small arms casings, a very common resource used in trench art making.

What does the crescent and “winged Z” indicate? The hand-tooling is quite ornate and aesthetically pleasing. I’d say that this was a solid score for my friend.

On one side, the maker tooled a pattern and left a smooth shield motif with what appears to be a monogram of the initials, “MB.” At the surrounding corners of the shield are “1914”,” 15”, “16” and “17” which clearly indicates the first few years of World War I.

Etched into the opposing side of the matchbox is what appears to be a crescent or “C” with the opening pointed upward. Inside the crescent are two wings – one, at the bottom, pointing to the left with the top one pointing to the right. Connecting the two wing tips is a heavy line running diagonally, right to left from the top to the bottom. All three pieces appear to form the letter “Z.” Superimposed over the diagonal line is a small numeral two. Over the top of this “winged Z” is appears the year, “1917.” To the top right is a star with radiant beams extending outward to all directions providing a backdrop design. The top panel is etched simply etched with “Champagne”, surrounded by tooled pattern.

The matchbox top has “Champagne” engraved. To me, this clearly indicates that the owner spent a good portion of WWI serving in these battles.

I knew that the piece was from WWI and was potentially French or British in origin (it could even be German) due to the dates of the piece, as the U.S. didn’t enter the war until 1917. Could the crescent indicate Arabic or Islamic participation? Could it be connected to the French Foreign Legion? Does “Champagne” refer to the battles that were fought in 1914, 1915, 1916 and 1917?

Due to the sheer beauty of this piece, it has proven to be a very wise investment my friend made (at least in my opinion) regardless of his lack of certainty about it. This matchbox will be a fun and interesting research project. Perhaps one of you recognizes the emblems or has any ideas? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Bataan/Corregidor POWs – Looking Back 75 Years

Five months. Depending upon your perspective, this span of time may seem to be a brief moment or a lifetime. If you are anticipating a well-planned vacation, you count the days down with excitement. If you are completing a career and your retirement date is approaching, you might have some anxiety about the significant change in life that you are facing. For the men on Corregidor in May of 1942, it was the culmination of a long-fought battle that was about to come to an end.

The Japanese had planned simultaneous, coordinated attacks on United States military bases in an effort to subjugate American resistance to their dominance in the Western Pacific. Seeking to seize control of natural resources throughout Asia and the South Pacific, the Empire of Japan had already been marching through China, and having invaded Manchuria in 1931, they continued with full-scale war in 1937 as they took Shanghai and Nanking, killing countless thousands during the initial days of hostilities. American sanctions and military forces, although not actively engaged, stood firmly in the Japanese path of dominance.

A copy of the transfer orders for the 5th Air Base Group, October 1941. My uncle’s father is listed here along with one other veteran who was with him throughout his entire stay as a guest of the Empire of Japan.

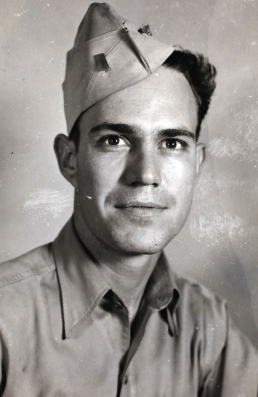

The father of my uncle (by marriage), enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1941 and was assigned to the Decontamination Unit of the 4th Chemical Company, one of 204 members of the 5th Air Base Group that had been transferred to the in Far East Air Force in the Philippines in late October. Like many other new privates, this man had enlisted to escape the tight grip of the Great Depression and massive unemployment, seeking steady pay while embracing a new life of service to his country. The Philippine Islands, though remote and thousands of miles away from the comforts of home, represented a certain measure of adventure. He was unaware what the next four years would bring.

On December 8, 1942, Japanese forces landed on Luzon in the Philippines as they kicked off what would become a lengthy campaign in an effort to gain control of the strategic location and to remove the threat of any resistance of their ever-expanding empire by the forces of the United States. Grossly under-prepared for war, the 150,000 troops (a combination of American and Philippine forces) were plunged into battle, defending against the onslaught of the 130,000 well-seasoned, battle-hardened enemy forces.

The American forces were almost immediately cut off from the promised supplies and reinforcements that would never be sent.

- 20th Air Force B-29s lined up (on Saipan) for post-surrender POW supply drop.

- An aerial photo (taken by 20th Air Force personnel) of one of the POW camps at Fukuoka.

- As they prepared to resupply them after the surrender of Japan, the 20th Air Force photographed and documented the locations of POW camps throughout Japan.

Over the course of the next five months, U.S. and Philippine forces fought a losing battle in an almost constant state of retreat as supplies wore thin and troops wore out. Exhausted, beat-up and starving, the defenders (of the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor) were done. Having suffered considerable losses (25,000 killed and 21,000 wounded), General Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright indicated surrender by lowering the Stars and Stripes and raising the white flag of surrender. More than 100,000 troops were now prisoners of war in the custody of the Imperial Japanese forces and would endure some of the most inhumane and brutal treatment every foisted upon POWs. My uncle’s father, a young private was now among the captured, on the march to an uncertain future.

An engraved mess kit from a Bataan veteran (photo source: Corregidor – Then and Now).

The five months of uncertainty and hopelessness that my uncle’s father experienced as a Bataan Defender since hostilities began would become years of daily struggles to survive in prison camps where beatings, starvation and executions were the new normal.

A POW letter to loved ones providing basic information of internment (photo source: Corregidor – Then and Now).

To say that Prisoner of War artifacts are a rarity is a gross understatement. POWs (captives of the Japanese) had to scrounge, steal and beg for basic necessities. Any personal possessions they might have had during the 80-mile forced march were taken once they arrived at makeshift camps. Those few captives who were crafty would manage to conceal small mementos, avoiding detection by the prison guards.

Aside from personal accounts of the atrocities that were told by liberated prisoners after the war, documentation proved helpful in war crime trials of the Japanese camp administrators. Prisoners ferreted away scarce paper and documented brutal acts and names of POWs who were killed or died of disease and starvation. Any of the items that were brought home by these men have tremendous significance as historical records and possess value well beyond a price tag.

May 6, 2017 marks the 75th anniversary of the surrender that launched a painful chapter in my uncle’s father’s life that remained with him for the rest of his years. Through my research, I have been able to determine that he was a POW at the Davao Penal Colony until it was closed in August of 1944. By the war’s end, he had been moved to Nagoya #5-B having made the trip to Japan aboard one of the infamous Hell Ships.

He never really talked about his experiences (at least with me). This man chose instead to let the past remain in its proper place. Unfortunately, I don’t know what might have become of any items he may have returned home with. My hope is that if they do exist, his POW artifacts are with his children or grandchildren, preserved in hopes that his experiences are not forgotten.

Bataan Prisoners of War References:

Provenance and Research Matters: WWII USAAF Aviator’s Cap

I doubt there are many collectors who have NOT experienced the current run that I’ve been on, though I certainly feel alone in this rut.

This khaki aviator’s ball cap is an oddity with this artwork on the bill. A sewn-on rank insignia adorns the front panel (source: eBay Image).

Over the past several months, I have been seeing some amazing online auction listings of seldom-seen militaria pieces. It seems that with each week that passes, an item gets listed that falls into one of my many robot-searches, alerting me to investigate and research the piece. After the necessary due diligence, I am reeled-in and decide what I can afford and get set to place my highest bid (yes, I use a sniping program). After a few days of waiting, I receive the dreaded notice that I had been outbid milliseconds after mine was placed.

A close-up of the hand-painted bill shows the “437th” in the squadron insignia (source: eBay Image).

Aside from the disappointment of being outbid, the other all-too-familiar letdown that I have been experiencing is the discovery of pieces that would fit perfectly into my collection but the price never seems to align well with my budget. Illustrating this point was when a stunning World War II-vintage aviator’s ball cap, complete with hand-painted squadron artwork was listed at auction.

When I first laid eyes on the khaki ball cap, I was immediately captivated by the hand painted checkerboard pattern surrounding the squadron insignia. Though the design was monochromatic, the design appeared amazingly crisp overlaying the painted-yellow background. My interests lie predominantly with naval history so my expertise is lacking with regards to knowledge of Air Corps squadrons. The “437th inscribed within the insignia was very difficult to research with investigative results being sketchy at that time. Since then, I was able to research further that the hat could most likely have come from an airman who served with the 437th Fighter Squadron (of the 414th Fighter Group) that flew P-47 Thunderbolts in protection of B-29s in the Pacific Theater (in the 20th Air Force).

- The cap appears to be a correct-vintage with the leather sweatband (source: eBay Image).

- In this undated WWII photo of the Tuskegee Airmen, notice the aviator ball cap worn by some of the men.

I have only found one single reference to the insignia that is painted onto the ballcap’s bill. It is taken from the unit’s squadron patch. This patch was part of a small group that included a photo and sold at auction for nearly $720.00 in 2014. (source: eBay image).

With no experience in these caps, I had no idea of the range of value for this cap. The one thing that put me off a bit was the initial bid price of $750. On one hand, it seemed to fit my perception of value, but without ironclad provenance (it had none) or any way to confirm the squadron identity, the price started to seem quite high. Too many questions coupled with the lack of sound seller-history, I couldn’t begin to ponder placing a bid even at half the asking price.

Since I first saw the cap, the seller has (unsuccessfully) listed the cap for auction a second time with a lower price. With being listed twice and not a single bid, one could infer that the cap isn’t worth the risk. But something in me keeps me guessing and wondering.

Perhaps I’ll just wait for the next amazing listing to pass on (or be passed on).