Category Archives: Flags

Two Hundred Forty Years of Steadfast Colors

On May 30th, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation to establish a national day of observance to honor the national ensign of the United States of America. Though the national annual observance wasn’t signed into law until President Truman did so in 1949, the annual recognition of honoring Old Glory was carried on by many Americans each year since 1916. With all that has transpired in the realm of politics within our nation, I suspect that rather than rendering honor to our flag, many of the people living within our borders will, instead choose to desecrate it…but I digress.

This illustration dates from 1885 and shows the first five flags of the U.S along with the (then) current configuration with 38 stars.

Flag Day (June 14) was set aside to encourage American citizens to display their nationalism, patriotism and civic pride by hoisting the national ensign on their homes, places of business and on public and government buildings. To put it simply, it is a day in which we show and honor the flag.

The Flag Day observances can be traced all the way back to 1885, when a teacher in a small town in Wisconsin decided that he would honor the flag. The National Flag Day Foundation cites,

Our mission is to carry on the tradition of the first flag day observance. On June 14th, 1885, Bernard J. Cigrand, a 19 year old teacher at Stony Hill School (located in Fredonia, WS), placed a 10 inch, 38- star flag in a bottle on his desk then assigned essays on the flag and its significance.

What is the significance of June 14 and why did Cigrand choose that date for recognition and rendering honors to the flag? In 1777, the second Continental Congress passed a resolution that stated,

Resolved, That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation.

There is significant debate as to who is credited for designing and creating that first flag of the United States–none of which I will discuss here, leaving it for you to make your own determination. Meanwhile, if you reside within a tolerable driving distance from the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia, you can take part in the final events of Flag Fest which concludes tomorrow, June 17, 2017.

For those seeking WWI or WWII period flags, 48 star flags are readily available in either vintage or excellent, weather-proof reproductions.

This week (as we do for each patriotic holiday) we are flying the Stars and Stripes in front of my home. Though we are consistent in honoring our current flag (thirteen stripes of alternating red and white; fifty stars, white in a blue field), I have considered acquiring and hoisting some of the historic iterations in its place.

Even if I could afford to purchase an antique iteration of the flag, obviously, I’d never run it up the staff, subjecting it to the elements thereby inflicting rapid deterioration and damage to the delicate fibers and stitching. Instead, locating high-quality reproductions (nylon, sewn and two-sided construction) of those historic colors that could stand up to the forces of nature are more reasonable and would afford me the opportunity to publicly display an area of my collecting interest.

This is a reproduction guidon for “I” company of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, 70th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers (known as “Rush’s Lancers”) is similar to the one I just ordered for my collection (source: eBay photo).

One of my most recent flag acquisitions is a hand-sewn reproduction of the regimental guidon of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (“F” company), the unit in which my 3-times-great grandfather served during the Civil War. I would love to have a period-correct original for my collection, but even if I had the financial resources, sourcing something with such rarity is next to impossible.

Happy 240th to Old Glory!

Following the Flag

Depicting the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment at Fort Wagner, SC, this (2004) painting, “The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground” by Rick Reeves prominently displays the flag leading the troops in battle.

Today is Flag Day. On June 14, 1777, Congress passed a resolution to adopt the stars and stripes design for our national flag. In honor of that, I felt compelled to shed some light on how the impact of the flag holds for men and women who serve this country in uniform.

Throughout the history of our nation, the Stars and Stripes have had immeasurable meaning to to those serving in uniform. On the field of battle, the Flag has been a rallying point for units as they follow it toward the enemy. From their vantage points, commanding generals are able to observe their troop movements and progress throughout battles by following the flag.

Troop reverence for the national ensign was no more apparent during the battle during the early American conflicts (Revolutionary War through the Civil War). Carrying the flag in battle was a considerable honor and the bearer was especially vulnerable to enemy fire. If the color bearer was wounded or killed, the colors would be dropped increasing the potential to demoralize the troops. If the bearer was incapacitated, another soldier would drop his weapon and pick up the flag, continuing to lead the unit toward the enemy.

In the 1989 TriStar film Glory (starring Matthew Broderick and Denzel Washington), Private Trip (Washington’s character) prevented the colors from hitting the ground when the flag bearer was shot during the assault on Fort Wagner. At that moment, the troops were mired in the hail of Confederate gun and cannon fire and the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment casualties were piling up. The troops, seeing the flag raised even higher, rose to the occasion and broke through walls of the fort.

Though Glory was a fictitious portrayal of actual events, a similar factual event took place in the November 25, 1863 Battle of Missionary Ridge in Tennessee. A young Union officer, 1st Lt. Arthur MacArthur (father of future General Douglas MacArthur) took up the regimental colors, taking it to the crest of Missionary Ridge and planting it for his regiment to see, shouting, “On Wisconsin” rallying the (24th Wisconsin Infantry) regiment. MacArthur, the last in a succession of color bearers (each falling during the assault on the ridge), was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action.

USS Grenadier crew member Engineman 1/c James Landrum holds the handmade American flag above a crowd of jubilant Omori Camp prisoners who were being liberated. August, 1945 (source: U.S. Navy photo).

Aside from their use on the battlefield, the Stars and Stripes has been known to rally servicemen and women to survive horrific and trying situations and conditions. In the numerous prisoner of war (POW) camps in Japanese-occupied territories and home-islands, American POWs were not permitted to possess a flag. When the Japanese military was on the verge of capitulation, the Americans gathered what materials they could to construct a flag which was captured in a famous image (snapped by an unknown photographer on August 29, 1945) of jubilant POWs celebrating their impending liberation.

Though I have seen the image countless times in my life, I never stopped to consider who the men were or what became of the flag. In my own collection, I have managed to maintain a few flag items of significant meaning (at least to me and my shipmates) from the first ship that I served aboard and until recently, I didn’t give them or any other flags a lot of thought. Instead my flags sat in boxes, tucked away for safekeeping. For the Omori POWs, the flag has a meaning that is tenfold more significant than the manufactured, government-issue items I possess.

My interest in this Omori POW flag was ignited when the daughter of WWI veteran Electrician’s Mate 3/c Charles Johnson, initiated a thread (on a militaria discussion board) in 2012 with a post detailing her pursuit of a hand-made flag that was made famous in a photograph of the liberation of an Allied POW camp in Japan. Her father was a survivor of the U.S. submarine, USS Grenadier (SS-210) and a POW at the Omori prison camp near Yokohama.

The daughter continued her post, “My father wondered what happened to the flag and was afraid it was molding away in someone’s attic (or) gotten thrown away by someone who did not know the story behind it.” She continued, “I promised him before he passed that I would continue to look for it.”

Over the course of the ensuing weeks, many helpful replies were submitted by forum members yet no certain leads on the flag were submitted. At the end of September a break in the daughter’s pursuit came when a gentleman submitted a post stating that he was the son of the man holding the flag (Engineman 1/c James D. “Slim” Landrum – USS Grenadier) when the photo of the POWs was taken.

The son of Landrum recalled his father’s story of how he attached the handmade flag to a fireman’s pike pole because he wanted the American flag to extend up higher above the others (displayed by the British and Dutch POWs). Afterward, the senior Landrum returned the flag to the fellow POW who supplied the bed sheet.

Armed with this information, the daughter of Petty Officer Johnson was able to locate a 1973 news article that told of the flag’s history and disposition. The Aomori camp flag was made by (then) Boatswain’s Mate 1/c Raymond Jakubielski (survivor of the USS Tanager – AM-5) and a handful of fellow POWs. In 1971, Jakubielski told the story, “In August when we heard from the camp grapevine that the Japs were about to surrender, I figured we ought to have a flag to welcome our boys in. Being the camp tailor, it was easy to get hold of an extra bed sheet and steal a couple colored pencils. Four of the mates helped color the flag and we had it up on the roof August 15, the day the Japs (sic) offered to surrender. Later, when the boats came to rescue us, our boys ran the flag up on a pole.” Having attained the rank of lieutenant prior to retiring from the navy, Raymond Jakubielski further remarked, “It was a welcome sight after seeing that rising sun thing around all the time.”

The Jakubielski family presented the flag to the U.S. Navy at Submarine Base in Norwich, Connecticut (Sunday, July 8, 1973) to Admiral Paul J. Early (a noteworthy veteran of the USS Nautilus’ submerged polar ice explorations known as Operation Sunshine) to be preserved for posterity. Subsequent to the gifting of the flag to the U.S. Navy, then-Connecticut senator Abraham A. Ribicoff arranged to have the flag flown over the U.S. Capital in tribute.

Though the information helped to close the loop for Charles Johnson’s daughter, the current disposition of the flag remained unknown. My curiosity had been piqued and I was subsequently prompted to reach out to the folks at the Naval Historical and Heritage Command. I requested information regarding the current location of the flag and, if it was in their possession, I asked if it would be photographed and shared within their Flickr photography collection. Several months after contacting them, I received the greatly anticipated affirmative response from the NHHC staff. They did, indeed have the flag within their collection and they had photographed and posted the flag at my request.

Purported to be the first American flag to fly over Tokyo, this 48-star flag was made from a white bed sheet and colored with colored pencils by prisoners at Sendai Camp No 11 in Omori Japan. It was flown in August, 1945 (source: collection of Curator Branch: Naval History and Heritage Command).

The conclusion to this story (locating the Omori flag), as happy as it may be for some readers, is not always a good one for a handful of collectors. The value in having an artifact of such incredible historical significance in the hands of archivists who will strive to preserve it and share it with the nation is immeasurable. Had the flag landed into a private collection or, worse yet, befallen the fate described by Charles Johnson, the history could have been lost.

Learn more about the American POWs in Japan:

- Submariner Prisoners of World War II

- Flags of Our POW Fathers

- Omori Tokyo Base Camp #1 Roster (Raymond Jakubielski, James Landrum)

- Fukuoka POW Camp, #3-B Roster (Charles Johnson)

Related Flag-Collecting Articles:

Ancestral Flag: A “Guidon” my Family History

Housed at the US Army Heritage Education Center (located in Carlisle, PA), this image shows one of the actual lances carried by 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry troops.

Years ago, I embarked on a project to document most (if not all) the members of my family’s ancestry who served in the United States armed forces. Researching genealogy can be quite a daunting task when pursuing such a specific theme within confines of a family history. The difficulty in that task is compounded when the there is little or no documentation available to begin with.

I began my research with the names that I knew on my list – my father, grandfather (only one served), uncles, grand uncles and so on. Merely working backwards two generations, I accounted for six veterans (five with combat experience). The third generation up is where I began to experience challenges (some parts of the family emigrated from Canada or the United Kingdom which adds another complexity layer to the research effort), but was able to persevere, discovering several more U.S. service members.

It was at the fourth generation (removed from me) that I discovered one veteran in particular that had really captured my attention. My 3-times great-grandfather was a veteran of the American Civil War (ACW). I took several notes of his vital information and continued searching. I found that two of his grandfathers and at least one great-grandfather were veterans of the Revolutionary War. With this information, I established a stopping point and began to focus on ferreting out as much data as I could find. I decided to hone in on the Civil War veteran and began exhausting all of the online resources.

After receiving two packets of information following a National Archives request (and several weeks of waiting) I began to piece together what my ancestor did during his time in service. Like thousands of young men across the Union, my great, great, great-grandfather, Jarius Heilig, volunteered (September, 1861) to serve alongside his (Reading, PA) neighbors and relatives, enlisting into the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (70th Pennsylvania Volunteers) – a unit formed by Colonel Richard Henry Rush (son of Richard Rush who was President Madison’s Attorney General and grandson of Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence), classmate and friend of General George McClellan.

One interesting fact about the 6th Penna is that their primary weapon. the lance (rather than the standard U.S. cavalry-issued carbine rifle), was suggested by McClellan, harkening to the once-feared European dragoons and cavalry units. The weapon is described as:

“The Austrian pattern was adopted. It was nine feet long, with an eleven inch, three edged blade; the staff was Norway fir, about one and a quarter inches in diameter, with ferrule and counterpoise at the heel, and a scarlet swallow-tailed pennon, the whole weighing nearly five pounds.”

Though injured (by a horse-kick, of all things) at the end of 1862, Heilig had seen his share of combat serving entirely with “F” company until his February 1863 discharge (due to disability), with action in the following battles and skirmishes:

-

Skirmish, Garlick’s Landing, Pamunkey River, VA (June 13, 1862)

-

Seven Days Battles, VA (June 25-July 1, 1862)

-

Battles, Gaines Mill, Cold Harbor, Chickahominy, VA (June 27, 1862)

-

Battle, Glendale, Frazier’s Farm, Charles City Crossroads, New Market Crossroads, Willis Church, VA (June 30, 1862)

-

Battle, Malvern Hill, Crew’s Farm, VA (July 1, 1862)

-

Skirmishes, Falls Church, VA (Sept. 2-4, 1862)

-

Skirmish, South Mountain, MD (Sept. 13, 1862)

-

Skirmish, Jefferson, MD (Sept. 13, 1862)

-

Action, Sharpsburg, Shepherdstown, and Blackford’s Ford (Boteler’s Ford) and Williamsport, MD (Sept. 19, 1862)

-

Actions, Bloomfield and Upperville, VA (Nov. 2-3, 1862)

Research resources are quite abundant for this unit (which I am still pouring through) and it has been the subject of a handful of books that were the product of painstakingly thorough historical investigation.

What does this have to do with militaria collecting, you might be asking? Part of my quest in producing a historical narrative of my familial military service is to provide visual and tangible references. To illustrate history, words are only part of the equation in connecting the audience to the story. To see, smell and touch a piece of history provides an invaluable accompaniment to the narrative.

I have given considerable thought to my approach in gathering items to assemble a group of artifacts as a “re-creation” of things my great-grandfather might have kept over the years. Visual appeal, authenticity, believability and cost were all factors guiding me as I purchase various pieces for the collection. My goal with the group is to arrange it into an aesthetically pleasing display that I can then hang on my home office wall (along with the displays I have already created).

Collecting artifacts from the American Civil War is not a task that can easily be easily accomplished on a shoestring budget (such as my own). Seemingly everything is expensive from weapons (rifles, pistols and edged weapons) down to ordinary uniform buttons seen on literally millions of soldiers’ uniforms. The high prices and the popularity of the Civil War’s historical popularity (which is maintained by pop-culture with films like Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln) can have detrimental effects on the market as unscrupulous counterfeiters work tirelessly to cash in.

Adding to my challenge is the fact that there were far fewer cavalry soldiers who served during the war. Even more challenging is that my ancestor served with a state volunteer cavalry regiment, many of which had extremely unusual uniform appointments and accouterments requiring even more research and discernment as to what my 3x-great grandfather would have been outfitted with.

These factors (combined with my own lack of experience) limited my focus to keep the pursuit as simplistic and affordable as possible while focusing on the more common ACW pieces for the display.

Since I embarked on this mission, I have acquired several pieces – a mixture of genuine and reproduction (recommended by a collector colleague) – that will display nicely together. From hat devices to corporal’s stripes (repro) to veteran’s group medals (GAR – Grand Army of the Republic – an ACW vets’ organization my ancestor was a lifelong member of). In addition, I’ve collected some small arms projectiles (from weapons Heilig would have carried) excavated from battlefields where my great-grandfather fought.

I am constantly on the lookout for pieces that would display well or that might be interesting additions to my militaria collection that could be directly tied to my ancestor’s unit. When a cavalry guidon flag (directly connected to the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry) was listed at online auction, my heart raced as I eagerly poured over the photos of the tattered and worn swallow-tailed cloth.

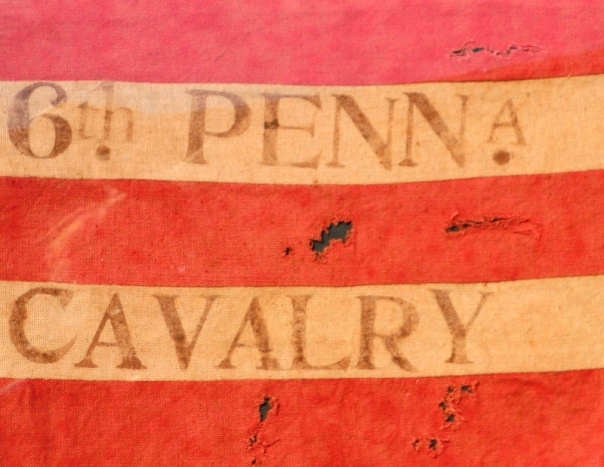

As was the custom of the Civil War, the major battles and engagements in which the unit participated were printed directly onto the stripes on the fly of the flag (source: eBay image).

Lost in the detailed images of the flag, I was amazed to see the faded relic nicely preserved in a frame behind glass. Bearing marks of the unit and the major battles printed directly on the red and white stripes, this flag appeared to be a true relic of the past. The the “I” designator in the blue canton (encircled by the white stars of the states) indicated that this was the guidon from I company (my great-grandfather served in company “F”). Everything about this flag excited me…until I read the description. The flag was a recreation of the original (which is permanently preserved and displayed at the Pennsylvania state house), right down to the synthesized aging (at least the seller was being honest about the piece).

Aside from the tell-tale swallow-tail design of the flag, the printed unit name indicates that this flag was from a cavalry regiment – specifically, the 6th Pennsylvania (source: eBay image).

The letter “I” in the center of the blue canton represents the associated company within the 6th Pennsylvania that used this guidon (source: eBay image).

Had the price of the auction been realistic, (the starting bid was $1,000), I would have been interested in pursuing it as a realistic accompaniment to the display I am assembling.