Monthly Archives: December 2016

The Spoils of War – To Whom Do They Belong?

“To the victor go the spoils.” While this quote by (then) New York Senator William L. Marcy was said regarding politics, it has been applied with regularity in reference to the taking of war prizes by the victor at the expense of the vanquished.

The taking of war prizes has been in play since the beginning of warfare and will probably continue into the unforeseeable future. The victorious, ranging from individual soldiers to military units and on up to the entire nation, maintain these treasures as symbolic of the price that was paid on the field of battle. Individuals maintain items as mementos of personal experiences and reminders of their own sacrifices. Some are painful reminders of comrades who died next to them in the trenches or aboard ship.

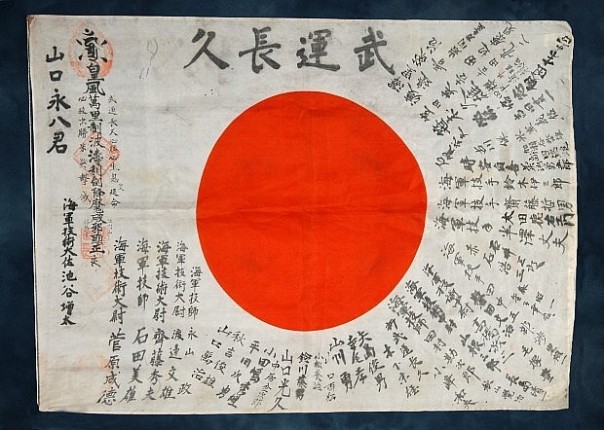

Mrs. Carol Conover, a NASIC employee, donated this flag to the NASIC history office years ago. It belonged to her father-in-law who brought it home from the Pacific after WWII. It is now back in the hands of Eihachi Yamaguchi’s family, the original owners.

In recent years, as aging American World War II veterans began to draw closer to their own mortality, thoughts of healing wounds that have remained open since returning home have begun to emerge. Many veterans like Clair Weeks began to see the personal items removed from dead enemy soldiers as having little personal value to them. Seeking to provide the dead enemy soldier’s surviving family members with the captured hinomaru yosegaki or “good luck” flag, Weeks began a quest to connect the item with relatives in Japan.

American museums have also taken steps to repatriate items. In Deltona, Florida, Deltona Veterans Memorial Museum staff are actively pursuing the return of a Japanese sailor’s possessions that were taken from his body by a U.S. Air Force pilot in Iwo Jima. These pieces include a silk, olive green ditty bag that held the sailor’s personal effects, a bamboo-and-paper folding fan, a Japanese flag and a collection of photographs.

Now on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, the blood-stained and bullet hole riddled ensign from the defeated USS Chesapeake (source: National Maritime Museum).

Constructed with timbers from the dismantled USS/HMS Chesapeake, the Chesapeake Mill still stands in Hampshire, England (source: Richard Thomas).

During the War of 1812 in a naval engagement between the USS Chesapeake and the HMS Shannon, the American frigate was overpowered (with 40-7 of the Americans killed in the battle) and captured by the British sailors. Taken as a prize, the Chesapeake was repaired and commissioned as the HMS Chesapeake. Upon her 1819 retirement from the Royal Navy, she was broken up with some of her timbers used to construct the Chesapeake Mill in Hampshire, England. In 1908, the blood-stained and bullet hole riddled naval ensign was sold at auction to Viscount William Waldorf Astor who, in turn, donated it to the National Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Today, the war prize flag is on public display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

Perhaps a having good, long-standing relationship with the United Kingdom contributed to the positive gesture of the 1996 repatriation of a piece of the Chesapeake’s timber to the United States. Americans can view the wood fragment at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum today.

These stories of war prizes being returned to their nations of origin are uplifting, if not inspiring. But there is another, less “sunny” war prize repatriation story afoot that has the stirred a significant amount of public outcry and resistance from U.S. veterans and military leadership.

Most Americans know very little about the conflict in the Philippines that immediately followed the end of the Spanish-American War in which the Americans received the island nation from the defeated Spanish for the sum of $20m. A small faction of Philippine nationals rose up in resistance to what was perceived as another imperialist ruling foreign nation. Seeking their independence, an uprising led by Emilio Aguinaldo lasted for three years from 1899-1902, yet some attacks on Americans continued for years.

The American survivors of the attack pose with one of the captured church bells used by Filipino insurgents to coordinate the attack against the Americans.

In a coordinated guerrilla attack upon soldiers of the U.S. 9th Infantry stationed in Balangiga (in Eastern Samar), 54 American soldiers were killed while nearly another 25 were wounded. In response to the attack, two U.S. Marine officers initiated a vicious reprisal, ordering all Filipino males 10 years of age and older bearing arms be shot. Both were subsequently courts-martialed. As part of the action against the insurgents, American soldiers captured three church bells that were used as signaling devices for coordinating the Filipino attack. The bells were shipped to the United States and have been central pieces of memorials to honor the soldiers that were brutally killed in the Filipino attack.

One of the bells from Belangigo as it appears incorporated into a monument to the fallen of the U.S. 9th Infantry (source: Military Trader).

Today, the Bells of Balangiga are the central point of controversy, in which the descendants of the insurgents who attacked the U.S. troops are seeking their return to the Philippines to be used to honor their “freedom fighters.” Many U.S. veterans see this as destroying a monument that honored the Americans who were killed and erecting a monument that instead honors their killers.

Since 1997, talks have taken place at the highest political levels between the two nations as the return of the bells could go a long way in garnering political and national relations capital for all involved should the decision be reached to repatriate the cherished bronze castings. Today, the bells remain as placed at what is now known as Francis E. Warren Air Force Base (formerly, Fort Russell).

No Campaigning Here: Badges for Military Service Members in the White House

As our nation draws nearer to Inauguration Day on January 20, 2017 we are settling down from an election cycle that saw voters increasingly blasted with political advertisements on television and radio along with the landscape being polluted with the signs of candidates from local, state and federal elections. Now that the streets and neighborhood landscape has been cleared of all the pro- or anti-candidate signs with only the die-hard, disillusioned still driving their cars with bumper stickers from their failed candidates, hoping to wake up to a different outcome. The time of year that I loathe the most has come to an end.

The obsolete White House Service Badge features a natural metal seal on the white field. When this bade was retired in 1964, it was replaced with the Presidential and Vice Presidential Service Badges.

As much as I have disdain for that season, there is a segment of collectors who thrive on the materials that are produced to grab the undecided voters’ attention and sway them to cast votes in the candidate’s favor. Does it work? That is a subject of much debate, but the materials created can be a treasure trove for collectors, especially when it comes to candidates for the office of the President of the United States.

As the above election items are clearly NOT my forte, there are some militaria pieces that hold my interest. Though they are connected to our nation’s highest office, these uniform accouterments have nothing to do with any individual president.

The obsolete White House Service Badge features a natural metal seal on the white field. When this bade was retired in 1964, it was replaced with the Presidential and Vice Presidential Service Badges.

On June 1, 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10879 establishing the Presidential Service Badge or PSB (and the associated Presidential Service Certificate). Prior to the issuance of the PSB, U.S. military personnel assigned duty at the White House offices including…

- Camp David

- Naval Administrative Unit

- White House Garage

- White House Army Signal Agency

- Air Force One

- HMX-1

- US Army Executive Flight Detachment

…were issued the White House Service Badge (WHSB). The design of this badge incorporated a gold-colored medallion with a field of white with the eagle of the presidential seal superimposed over the center.

There is no arguing that this is one of the most beautifully designed U.S. military badges and it is a pleasure to have one in my collection.

Superseding the WHSB in 1964 was the Presidential Service Badge. The badge was a slight departure from the WHSB, changing the field from white to blue and adding a ring of white, 5-pointed stars around the field’s inner circumference. Each PSB is individually and uniquely numbered. Each number is associated to the person to whom that individual badge was issued, making each one trackable. The PSBs come with a three-prong clutch-back to affix it to the wearers’ left breast pocket.

In addition to the staff assignments listed above (for the White House Service Badge), military aides who carry the “Football” and White House military public affairs officers.

Vice Presidential aides, like those serving the President, are also issued a badge that is nearly identical to the defunct White House Service Badge with the difference being a gold (versus silver) colored seal as well as a variation with the gold edge thickness and design.

- This Presidential Service Badge is still sealed in the plastic in the original government-issued, no frills box. I am half-tempted to open the package to see the serial number.

- The reverse side of the badge shows the clutchback prongs and clutches and the (obscured) serial number.

- Much more understated than the PSB, the Vice Presidential Service Badge is more similar to the original (obsolete) White House Service Badge.

Just as awarded medals and ribbons, both the Presidential and Vice Presidential Service Badges remain a permanent part of the service members’ uniforms for the remainder of their military careers, even after their duty with the elected officials has been fulfilled.

These badges are fantastic additions to collectors of both militaria and presidential items.

A Piece of the Day of Infamy or Simply a Connection to an Historic Ship?

For most Americans, this time of year spurs thoughts of lighted trees, large and rotund red-suited elves, massive crowds at local shops and mega malls, anxiety, and ever-increasing credit card debt in the rush to obtain the perfect gift for loved ones and friends. All of this translates into the hopes that the recipients of said gifts illuminate with unbridled joy and gratitude. Meanwhile, a continuously diminishing segment of the population, in addition to the aforementioned seasonal activities and concerns, recall a monumentally tragic and infuriating event, now 75 years hence.

The USS Arizona’s bow pitches upward on the high seas sometime in the late 1930s (source: U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command).

At that time (three quarters of a century ago), Americans, like today, were in the throes of an economic depression while war and conflict littered regions around the globe. Many Americans had been without work for months, while others had been unemployed for years. The holiday season was in full swing but on an infinitely smaller scale. All of this about to change, catapulting the nation into chaos and doubt while transforming the nation’s doubt into a singular mindset, while rising from the literal ashes and wreckage to defeat fascism.

A rare color image showing the USS Arizona’s forward magazine detonating after it was struck by a high altitude aerial bomb (Source: U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command).

The World War II generation is departing our society at an increasingly accelerated pace. The men and women who banded together on the war front and home front still recall the Day of Infamy, remembering those who fell prey to unpreparedness and bumbling governmental bureaucracy and a dastardly attack. When the final tally was counted in the weeks and months following December 7, 1941, more than 2,400 Americans were dead at the hands of the Empire of Japan. Three battleships of the U.S. Navy were complete losses. One of those ships, the USS Arizona (BB-39), was obliterated by an aerial bomb that penetrated into the forward magazines (for the 14” guns), igniting a cataclysmic explosion, killing 1,117 sailors, accounting for more than half of the Pearl Harbor attack death toll.

The memorial structure straddles the stricken ship’s hull as she rests in the mud and silt of Pearl Harbor.

In the 75 years since that fateful day, much has transpired to cause the slow evaporation of Pearl Harbor memories of from the American conscience. The current younger generation experienced their own day of infamy 11 years ago with the 9/11 attacks, fueling the 12/7/41 forgetfulness with redirected angst.

Conversely for militaria collectors, the events of Pearl Harbor are held close to the vest and worn on their sleeves. The pursuit to hold a piece connected to that tragic day isn’t taken lightly. More often than not, collectors pay an extremely high premium for the honor of preserving and displaying items that tell the individual stories of the struggle to survive and the will to fight the attackers. Collectors treasure anything directly related to a veteran, aircraft or ship that participated in warding off the Japanese onslaught.

Inside the Arizona Memorial, this wall bears the names of the 1,177 victims who were killed on that tragic day.

For me, the realization of the Pearl Harbor collector mindset truly occurred for me awhile ago when I spotted an auction listing for a flat hat from a navy veteran that served aboard the most notable ship casualty of the attack, the Arizona. I scanned through the associated photographs, noting the condition while attempting to approximate the age of the item.

Worth its weight in gold, this flat hat recently sold for nearly $900 at auction (source: eBay image).

By 1941, operation security had been steadily increasing due to the waging war, both in Europe and the Western Pacific. The Navy, seeking to reduce the visible indications of ship movements, stipulated in uniform regulations that all ship identifiers, such as ship-name tallies on enlisted blue flat hats, be omitted from uniforms. Generic “U.S. Navy” lettered tallies replaced the those bearing the names of ships which meant that the one in the auction listing predated WWII by at least a year. However, this particular cap is a pre-1933 design that has had the stiffener removed leaving a more “slouched” appearance that became standard with the 1940s caps.

- Though the lettering is faded and shows some signs of the bullion thread corroding, this USS Arizona enlisted sailor’s flat hat is a rarity and is well worth the investment (source: eBay image).

- The real value of the USS Arizona flat hat is in the tally. Due to the historic-nature of the famous ship and the scarcity of tallies bearing ship names, the damage seen here had little impact on the final selling price of the hat (source: eBay image).

- Condition is everything. This hat has some serious issues from moth damage and was repaired at some point (source: eBay image).

- Top of the USS Arizona flat hat – showing the moth holes (source: eBay image).

- This view shows the inside of the Arizona hat and gives some indication to the age – the liner does appear to be post World War I (source: eBay image).

- Details of the flat hat – showing how the tally is tied into the traditional bow at the side of the hat (source: eBay image).

The condition of the hat left lots to be desired. From dozens of small holes scattered across all of the woolen surfaces, it was readily apparent that moths had a field day as they enjoyed their “hat salad.” The only components on this cap untouched by the Lepidoptera larvae were the tally and the liner.

What would be a significant value-increasing factor is if the hat bore the name of its owner. I was unable to discern from the provided photos any hint of a stenciled or inscribed name. If I had been able to see the original owner’s name, I might have been able to locate related details concerning his naval service, and quite possibly, the dates he served aboard the Arizona. It might be safe to assume that the value of the hat increases if the veteran did survive the ship’s sinking. However, based upon the features of the hat (the overall design, the liner and the tally), I would surmise that the hat is closer to the World War I-era.

Regardless of when the hat was used or if it belonged to a survivor of the Pearl Harbor attack, the auction’s final, closing bid of $848.00 was astonishing. Without a doubt, the winning bidder took a chance on acquiring an extremely rare piece with direct ties to a historic ship. In doing so, this collector now possesses a tangible connection to that fateful day.

See also: