Researching After You Buy – Sometimes it is the Better Option

I’ve said it so many times in the past: it is paramount to making wise purchases that collectors research an item prior to handing over hard-earned finances to make a purchase. However, there are occasions within militaria collecting where the collector is stumped by what he or she might be looking at, yet still feel compelled to pull the trigger on a deal to acquire it.

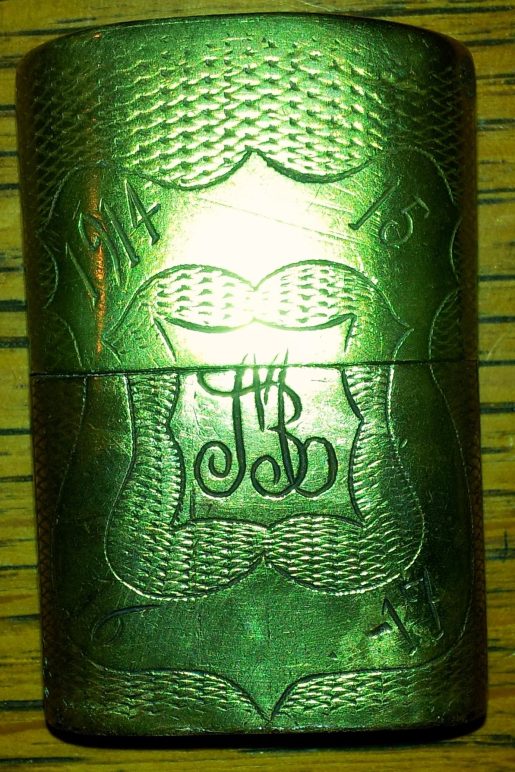

Recently, a very dear friend and fellow collector presented me one of his most recent acquisitions and wanted to get my input as to the markings and what they might indicate. He was stumped by some of the heraldry and details but there were other engraved elements that showed the piece to be from World War I.

The dates of 1914, 15, 16 and 17 automatically rule out this matchbox as being a U.S. trench art piece.

I spent several minutes examining what appeared to be a trench art matchbox. Clearly, the item shown is constructed from brass and was handmade. The brass plates were rolled out and soldered together to form an oblong can-shape with another piece cut and soldered into place at the top. A piece of wood was shaped and fastened to comprise the case’s bottom, and adhered with some sort of clear glue or shellac. Judging from the length of the box, the brass was an unrolled and flattened small arms casings, a very common resource used in trench art making.

What does the crescent and “winged Z” indicate? The hand-tooling is quite ornate and aesthetically pleasing. I’d say that this was a solid score for my friend.

On one side, the maker tooled a pattern and left a smooth shield motif with what appears to be a monogram of the initials, “MB.” At the surrounding corners of the shield are “1914”,” 15”, “16” and “17” which clearly indicates the first few years of World War I.

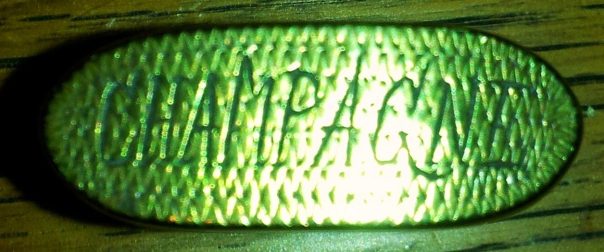

Etched into the opposing side of the matchbox is what appears to be a crescent or “C” with the opening pointed upward. Inside the crescent are two wings – one, at the bottom, pointing to the left with the top one pointing to the right. Connecting the two wing tips is a heavy line running diagonally, right to left from the top to the bottom. All three pieces appear to form the letter “Z.” Superimposed over the diagonal line is a small numeral two. Over the top of this “winged Z” is appears the year, “1917.” To the top right is a star with radiant beams extending outward to all directions providing a backdrop design. The top panel is etched simply etched with “Champagne”, surrounded by tooled pattern.

The matchbox top has “Champagne” engraved. To me, this clearly indicates that the owner spent a good portion of WWI serving in these battles.

I knew that the piece was from WWI and was potentially French or British in origin (it could even be German) due to the dates of the piece, as the U.S. didn’t enter the war until 1917. Could the crescent indicate Arabic or Islamic participation? Could it be connected to the French Foreign Legion? Does “Champagne” refer to the battles that were fought in 1914, 1915, 1916 and 1917?

Due to the sheer beauty of this piece, it has proven to be a very wise investment my friend made (at least in my opinion) regardless of his lack of certainty about it. This matchbox will be a fun and interesting research project. Perhaps one of you recognizes the emblems or has any ideas? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

2017: My Prolific Year of Writing and Research and Gaining Readership

I know that I can be retrospective in viewing where I have been throughout my life. I tend to keep my thoughts between my wife and me as they mostly pertain to us and the blessings and challenges that we have experienced. This year has only hours remaining and I have found myself looking back through the twelve months that have transpired to see what we have faced. However, I am reminded that those of us who enjoy history can also get too focused on what has already happened and overlook today and be complacent about planning and setting goals for the future. In looking back through the past year, I have made some interesting discoveries for my collection and historical research (as can be seen in the 49 articles that I have published on 2016, including the one you are reading) while adding some significant pieces.

Though technically I did not acquire this 1936 yardlong photo of the destroyer, USS Smith in 2017, It sat in a box until I discovered it this year

In reviewing what I have enjoyed as military history collector, researcher and amateur writer, I am astounded that I was able to publish nearly 50 articles while being a husband, father and working full-time and logging thousands of miles on my bicycle. As a family, we traveled a bit this year – three family trips to other parts of this country – tying in visits to significant historic locations and sites (which tend to be associated with important military events) to educate ourselves and our children. One of my children graduated high school and flew the nest as he embarked upon his career in the U.S. Air Force. We also suffered through an extended period of joblessness. Because of the loss of my job and other factors, my acquisitions slowed to a standstill, however leading up to that point, I landed some pieces that were, for me, nothing short of incredible.

In terms of my writing and my largest output of published articles since I started this project in 2013 (17 article published in that first year), this site has truly begun to grow in terms of readership doubling but viewers and pages viewed from 2015 to 2016 and doubling again this year (reaching 20,000 views and 10,000 visitors). I do so little to publicize this site choosing instead to allow the articles to surface in searches that the growth is even more impressive, at least by my own low standards. Despite the growth in readership, I am still amazed that anyone finds my subject matter interesting. I am the first to admit that my prose is rather bland (at best) if not dull and yawn-inspiring so the exponential increase in readers is difficult to fathom.

This 1943-44 USMC white home jersey was a significant find this year in that it is the only one that I have seen in nearly 10 years of researching military baseball. The blue cap (with the USMC gold “M” was also an important discovery this year).

Not only did I find one USMC baseball cap, but two within a few months of each other. This one appears to accompany the red cotton Marines baseball uniform that I acquired a few years ago.

My other military history site (Chevrons and Diamonds) is also beginning to gain viewers and readership though the subject matter there (military baseball history) has an even smaller audience. In slightly more than 25 months, I have published 37 articles (22 this year) that focus entirely upon artifacts, players, teams and other aspects of the game of baseball within the ranks of the United States armed forces. Since I acquired my first WWII Marine Corps uniform nearly a decade ago, delving into this area of collecting has truly been a mission of discovery and enjoyment. People are just beginning to discover this site as the traffic is steadily increasing (tripling last year’s growth) though it pales in comparison to what this site is experiencing.

I don’t know what 2018 will bring for me in terms of collecting, researching, writing and publishing. I am planning on having another public display (my two previous showings: Enlisted Ratings and Uniforms in 2017 and Military Baseball in 2015). The theme for this coming year will be centered upon the centennial of World War I and will force me to take inventory of my collection in order to assemble a compelling display of artifacts to share with the public. My two previous experiences with sharing my collection have been rewarding. I suppose that aside from my own personal enjoyment of the artifacts and their history, sharing what I have collected in order to provide a measure of education for others is one of my objectives with this passion. What is the purpose of collecting and researching these artifacts if it is kept entirely to myself? As long as I am capable of balancing my marriage, children, health and career with this passion, I will continue to write and share my collecting interests within the realm of these two blogs. As to looking back at what I have been through this year, I am happy to take a few rear-facing glances as I move ahead in gratitude for everything.

To everyone who reads these pages my hope is for a happy 2018 to you all.

Happy New Year!

Learning to Listen to that Quiet Voice of Reason: A Medal That Wasn’t Quite Right

You see the militaria item and at first glance, it looks great. Your heart starts racing as you begin to realize that you’re finally getting your hands one a highly sought-after piece of history. Understanding the story behind the piece, the sweat begins to bead on your forehead. “Could this be one of those?” you question yourself. The convincing thoughts race through your mind as you begin to dig through your wallet for the credit card thinking,“I am sure of it!”

Fighting back any thoughts of doubt, you hurriedly pay for the treasure. Once in your hands, you begin to begin to examine the details. The doubts come rushing back along with the possibility that regret will soon follow. This scenario is bound to happen, even to the most seasoned experts. Eventually, every collector will experience the letdown upon the discovery that they rushed into a purchase ignoring all the education and experience that would have protected them from buying a fake.

My experience came last year when I spotted a much coveted Navy Expeditionary Medal with the rare Wake Island clasp affixed to the ribbon. The medal (with the clasp) was awarded only to those sailors and marines who served in defense of Wake Island in December, 1941 from the 7th to the 22nd.

More than 450 Marines and nearly 70 naval personnel bravely repelled multiple Japanese aerial and naval bombardments and landing assaults as the Japanese attempted to wrest the island away from the U.S. forces. Severely outnumbered more than five to one, the Americans finally surrendered Wake to the enemy. Suffering 120 killed in action and 50 wounded, the Americans inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese forces sinking two destroyers and two patrol boats as well as heavily damaging a light cruiser. Japanese landing forces suffered 820 killed and more than 330 wounded in action.

My 1950s HLP-made Navy Expeditionary Medal with the fake Wake Island clasp.

My “fake” medal consists of a late 1950s authentic Navy Expeditionary medal with HLP (for the maker, His Lordship Products, Inc.) stamped into the rim of the planchet. The details of the strike are quite fine and even the most subtle areas of the design are quite crisp. The planchet is significantly thicker than a modern strike and is devoid of the modern synthetic antiquing. The brooch indicates that it is from the late ‘50s to early ‘60s.

To compare, this Wake Island clasp for the Navy Expeditionary Medal appears to be authentic. Note the crisp lettering and sharpness to the detail of the rope-border (source: eBay image).

Where the trouble with this medal starts to surface is with close examination of the Wake Island clasp. Ignoring the Rube Goldberg hack-job on the reverse (which can be overlooked…I have seen other claps butchered, although not quite as bad as this), the face is where I should have focused my initial attention.

- Showing the detail of the “WAKE” lettering and border (source: eBay image).

- Note the crisp lettering and the rope border (source: eBay image).

- The back side of the Wake Clasp (source: eBay image).

Upon a close examination of the field (of the clasp), I noticed the bumpy surface between the lettering and the edge where it should have been smooth. I also noticed that the lettering and the rope-design that surrounded the face all looked blurry or soft (as opposed to being crisp and sharp). All of these issues should have set off alarm bells in my head. All of these discernible issues indicate that the clasp was a forgery – a product of sand mold-casting, which is a cheap reproduction method that is routinely employed in these forgeries.

I will chalk this episode up as a lesson learned. I am keeping this medal in my collection as both a reminder and a nice “filler” as I will probably never be able to afford an authentic example. Everything else about the medal, suspension and clasp is makes this an otherwise very nice example of an early Navy Expeditionary Medal.