Category Archives: US Navy

Following the Flag

Depicting the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment at Fort Wagner, SC, this (2004) painting, “The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground” by Rick Reeves prominently displays the flag leading the troops in battle.

Today is Flag Day. On June 14, 1777, Congress passed a resolution to adopt the stars and stripes design for our national flag. In honor of that, I felt compelled to shed some light on how the impact of the flag holds for men and women who serve this country in uniform.

Throughout the history of our nation, the Stars and Stripes have had immeasurable meaning to to those serving in uniform. On the field of battle, the Flag has been a rallying point for units as they follow it toward the enemy. From their vantage points, commanding generals are able to observe their troop movements and progress throughout battles by following the flag.

Troop reverence for the national ensign was no more apparent during the battle during the early American conflicts (Revolutionary War through the Civil War). Carrying the flag in battle was a considerable honor and the bearer was especially vulnerable to enemy fire. If the color bearer was wounded or killed, the colors would be dropped increasing the potential to demoralize the troops. If the bearer was incapacitated, another soldier would drop his weapon and pick up the flag, continuing to lead the unit toward the enemy.

In the 1989 TriStar film Glory (starring Matthew Broderick and Denzel Washington), Private Trip (Washington’s character) prevented the colors from hitting the ground when the flag bearer was shot during the assault on Fort Wagner. At that moment, the troops were mired in the hail of Confederate gun and cannon fire and the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment casualties were piling up. The troops, seeing the flag raised even higher, rose to the occasion and broke through walls of the fort.

Though Glory was a fictitious portrayal of actual events, a similar factual event took place in the November 25, 1863 Battle of Missionary Ridge in Tennessee. A young Union officer, 1st Lt. Arthur MacArthur (father of future General Douglas MacArthur) took up the regimental colors, taking it to the crest of Missionary Ridge and planting it for his regiment to see, shouting, “On Wisconsin” rallying the (24th Wisconsin Infantry) regiment. MacArthur, the last in a succession of color bearers (each falling during the assault on the ridge), was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action.

USS Grenadier crew member Engineman 1/c James Landrum holds the handmade American flag above a crowd of jubilant Omori Camp prisoners who were being liberated. August, 1945 (source: U.S. Navy photo).

Aside from their use on the battlefield, the Stars and Stripes has been known to rally servicemen and women to survive horrific and trying situations and conditions. In the numerous prisoner of war (POW) camps in Japanese-occupied territories and home-islands, American POWs were not permitted to possess a flag. When the Japanese military was on the verge of capitulation, the Americans gathered what materials they could to construct a flag which was captured in a famous image (snapped by an unknown photographer on August 29, 1945) of jubilant POWs celebrating their impending liberation.

Though I have seen the image countless times in my life, I never stopped to consider who the men were or what became of the flag. In my own collection, I have managed to maintain a few flag items of significant meaning (at least to me and my shipmates) from the first ship that I served aboard and until recently, I didn’t give them or any other flags a lot of thought. Instead my flags sat in boxes, tucked away for safekeeping. For the Omori POWs, the flag has a meaning that is tenfold more significant than the manufactured, government-issue items I possess.

My interest in this Omori POW flag was ignited when the daughter of WWI veteran Electrician’s Mate 3/c Charles Johnson, initiated a thread (on a militaria discussion board) in 2012 with a post detailing her pursuit of a hand-made flag that was made famous in a photograph of the liberation of an Allied POW camp in Japan. Her father was a survivor of the U.S. submarine, USS Grenadier (SS-210) and a POW at the Omori prison camp near Yokohama.

The daughter continued her post, “My father wondered what happened to the flag and was afraid it was molding away in someone’s attic (or) gotten thrown away by someone who did not know the story behind it.” She continued, “I promised him before he passed that I would continue to look for it.”

Over the course of the ensuing weeks, many helpful replies were submitted by forum members yet no certain leads on the flag were submitted. At the end of September a break in the daughter’s pursuit came when a gentleman submitted a post stating that he was the son of the man holding the flag (Engineman 1/c James D. “Slim” Landrum – USS Grenadier) when the photo of the POWs was taken.

The son of Landrum recalled his father’s story of how he attached the handmade flag to a fireman’s pike pole because he wanted the American flag to extend up higher above the others (displayed by the British and Dutch POWs). Afterward, the senior Landrum returned the flag to the fellow POW who supplied the bed sheet.

Armed with this information, the daughter of Petty Officer Johnson was able to locate a 1973 news article that told of the flag’s history and disposition. The Aomori camp flag was made by (then) Boatswain’s Mate 1/c Raymond Jakubielski (survivor of the USS Tanager – AM-5) and a handful of fellow POWs. In 1971, Jakubielski told the story, “In August when we heard from the camp grapevine that the Japs were about to surrender, I figured we ought to have a flag to welcome our boys in. Being the camp tailor, it was easy to get hold of an extra bed sheet and steal a couple colored pencils. Four of the mates helped color the flag and we had it up on the roof August 15, the day the Japs (sic) offered to surrender. Later, when the boats came to rescue us, our boys ran the flag up on a pole.” Having attained the rank of lieutenant prior to retiring from the navy, Raymond Jakubielski further remarked, “It was a welcome sight after seeing that rising sun thing around all the time.”

The Jakubielski family presented the flag to the U.S. Navy at Submarine Base in Norwich, Connecticut (Sunday, July 8, 1973) to Admiral Paul J. Early (a noteworthy veteran of the USS Nautilus’ submerged polar ice explorations known as Operation Sunshine) to be preserved for posterity. Subsequent to the gifting of the flag to the U.S. Navy, then-Connecticut senator Abraham A. Ribicoff arranged to have the flag flown over the U.S. Capital in tribute.

Though the information helped to close the loop for Charles Johnson’s daughter, the current disposition of the flag remained unknown. My curiosity had been piqued and I was subsequently prompted to reach out to the folks at the Naval Historical and Heritage Command. I requested information regarding the current location of the flag and, if it was in their possession, I asked if it would be photographed and shared within their Flickr photography collection. Several months after contacting them, I received the greatly anticipated affirmative response from the NHHC staff. They did, indeed have the flag within their collection and they had photographed and posted the flag at my request.

Purported to be the first American flag to fly over Tokyo, this 48-star flag was made from a white bed sheet and colored with colored pencils by prisoners at Sendai Camp No 11 in Omori Japan. It was flown in August, 1945 (source: collection of Curator Branch: Naval History and Heritage Command).

The conclusion to this story (locating the Omori flag), as happy as it may be for some readers, is not always a good one for a handful of collectors. The value in having an artifact of such incredible historical significance in the hands of archivists who will strive to preserve it and share it with the nation is immeasurable. Had the flag landed into a private collection or, worse yet, befallen the fate described by Charles Johnson, the history could have been lost.

Learn more about the American POWs in Japan:

- Submariner Prisoners of World War II

- Flags of Our POW Fathers

- Omori Tokyo Base Camp #1 Roster (Raymond Jakubielski, James Landrum)

- Fukuoka POW Camp, #3-B Roster (Charles Johnson)

Related Flag-Collecting Articles:

Patrolling for Patches: Seeking the Hard-to-Find Embroidery

People start collecting military patches for a number of reasons. Considering that all branches of the United States armed forces use embroidered emblems for a multitude of purposes ranging from markings of rank and rating to unit and squadron insignia, invariably, there is something worthwhile to catapult even the non-militaria collector into pursuing the colorful cacophony of patch collecting.

My own participation in collecting patches originates with my own service in the navy. What began back in those days as an effort to adorn my utility and leather flight jackets with colorful representations of my ship and significant milestones (such as deployments) morphed into a quest to complete a shadow box that would properly represent my career in the service. Many of the patches I acquired while on active duty never found their way into use and were subsequently stashed away. It was not until I began to piece together items from my career that my patch collecting interest was ignited.

Like many other military patch collectors, I expanded my hunt from a narrow focus to a much more broad approach. As I pursued patches for another shadow box project (for a relative’s service) I started to see “deals” on random insignia that I just couldn’t live without. It wasn’t before long that I had a burgeoning gathering of embroidered goodies from World War II ranging from those from the US Marine Corps, US Army Air Corps/Forces and other ancillary US Army corps, division and regimental unit insignia*. For the sake of preserving what little storage space I had available, I throttled down and began to narrow my approach once again.

In keeping with my interest in naval history in concert with my passion for local history (where I was born and raised), my military patch collecting went in a new direction. In the past several years, I have slowly acquiring items associated with several of the ships with Pacific Northwest connections. Aside from readily available militaria associated with the USS Washington, USS Idaho and USS Oregon (all of which have stellar legacies of service). items from the ships named for the various cities (in those states) pose much more of a challenge to locate. When it comes to collecting patches, that difficulty is exponentially increased.

USS Tacoma (PG-92). (Source: U.S. Navy)

Of the many ships named for locations or features within Washington State, the four ships named for the City of Tacoma leave very little for a military patch collector to find, considering that only one of the four served in the era when navy ship patches came into use. The USS Tacoma (PG-92), a patrol gunboat of the Asheville class was actually built and commissioned in her namesake city, served for 12 years in the U.S. Navy from 1969 to 1981. Though her career was relatively brief, she spent her early years operating in the Pacific and in the waters surrounding Vietnam conducting patrol and surveillance operations, earning her two battle stars for her combat service.

This USS Tacoma (PG-92) ship’s crest shows an American Indian and “Tahoma” (Mt. Rainier) in the background. The motto, “Klahow Ya Kopachuck” translates from the Chinook language to “greetings for travelers upon the water.”

While searching for anything related to the USS Tacoma (all ships) last year, a patch from the PG-92 showed up in an online auction that really spoke to me. It was rather expensive and there were many bidders competing for the patch, so I let it go without participating. A few months later, another copy of the patch was listed prompting me to watch for bids. With no bids after a few days, I set my snipe with the understanding that someone is going to exceed my price. One bid came in seconds before the auction closed but my snipe hit at the very last second which resulted in successful outcome for me (winning the auction). It wasn’t until it arrived that I saw the ink-stamp mark on the back. It might be a bit of a detractor, but it certainly isn’t a deal breaker for this vintage 1970s-era patch. However, the patch I received most recently gives me pause.

The second USS Tacoma patch looked fantastic when viewed online even with the staining. The flag-theme evokes memories of 1975-76 and the celebration of the bicentennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. On the blue canton, the “PG” encircled by the stars (there are only 10 rather than 13) refers to the hull classification of the ship. Besides the incorrect count of stars, the backing material and the construction of the embroidered edge lead me to believe that this patch was made in Asia. The staining seems as though it was added to the patch to give it some aging.

This USS Tacoma patch seems to be a recently manufactured item. I have my doubts as to it being an original mid-1970s era creation.

Another indication of (what I believe to be) the Spirit of 92 patch’s recent manufacture is that it smelled new. I opened the mailing pouch and the scent of new fabric (rather than a musty odor) wafted out which seems quite strange for an old patch.

Regardless of the veracity of the age, both patches are excellent additions to my meager collection.

*Related patch-collecting articles by this author:

- Collecting U.S. Navy Uniform Ship Identifiers

- Collecting Olympics, Militaria-Style!

- Forecasting Patchy Skies: Sew-on Naval Aviation Heraldry

- US Marine Corps Uniform: Shoulder Sleeve Insignia Introduction

- USMC Patch Rarities and Scarcities – What to Look For

- Theater-Made Militaria

A Uniform for an Ordinary Joe

There are times when I find myself with so many topics to write about that my mind wanders so rampantly that I am left with seemingly nothing to cover. It is akin to my wife walking into our closet (that is filled with clothes) and finding nothing to wear.

I look back on all that I have covered during the past 15 months (including my year of writing for CollectorsQuest) in an attempt to avoid repeating myself. I check my collection for items that I haven’t covered yet (there is an abundance at the moment) while looking ahead at some event/calendar-based ideas that I am working on and I realize that I can begin to narrow the field a little. I can focus in on a subject knowing that as this article begins to develop, it may very well transform into something vastly different when I am ready to publish it.

Speaking of closets filled with nothing to wear, there among the garments that I rotate through each week are several garment bags packed full of military uniforms. While some of the uniforms were worn during my naval career and a few others belonged to my grandfather, the lion-share are truly pieces in my modest collection (dominated with U.S. Navy uniforms). Looking at the last few articles that I’ve written for this blog are Navy-focused, I am pushed toward covering one of the two non-Navy uniforms in my possession.

Why collect uniforms someone (new to militaria collecting) might ask? For me at least, the idea of possessing a tangible object that was worn by a service member (especially during a significant period of our nation’s history) provides a sensory connection (sight, scent, touch) that is unattainable with written words or images. In addition, the uniforms themselves possess some elements and characteristics that make them, on their own, aesthetically pleasing.

My uniform collection, when compared with that of other (long-term) collectors, is quite humble and ordinary when it comes to the identities of the veterans who previously owned and wore the items. This is not to suggest that anyone’s service to this country is ordinary, but in comparison to veterans whose careers shaped and impacted history (so much so that their names are legendary because of their battlefield deeds), my uniforms are quite modest.

One colleague owns (or owned) uniforms that would make almost any collector salivate at the mere thought of touching, let alone owning. Imagine having the uniform from the man who, while in command of a diminutive destroyer escort, bore down on Japanese task force that consisted of four battleships (including the Yamato), eight cruisers and several destroyers in order to protect the carriers in his own task force? That commanding officer, Robert Copeland risked himself, his ship and his crew in order to successfully protect the American carriers from certain destruction near Samar in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Copeland received the Navy Cross for his actions that day in October of 1944.

Post-World War II Khaki uniform jacketm dress blues and combination cover, worn by Navy Cross recipient, Admiral Robert Copeland (image source: ForValor.com/Dave Schwind)

This World War I – era U.S. Navy frock coat belonged to (then) Captain Frank Schoflield. Note the ornate bullion collar devices and the pre-WWI sewn-on ribbons (image source: USMilitariaForum.com/Dave Schwind).

The shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) for the 1st Marine Division. This patch is affixed to the left shoulder of a 1943-dated USMC uniform jacket.

Not everyone has the finances or the perfect timing to locate items from such legendary people. Some collectors seek uniforms that serve to illustrate a story or, perhaps to demonstrate the progression of uniform changes throughout history. In either case, high-dollar uniforms from well-known figures (of American history) would serve to highlight such a story line but are not necessarily needed pieces. For those who (with limited budgets) want to pursue something from a specific (i.e. monumental) period of military history, “settling” for uniforms from the common soldier, airman, sailor or Marine.

I am particularly interested in the history surrounding the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO) when discussing or researching World War II. Being a Navy veteran and the grandson of a WWII PTO Navy veteran, my collection tends to be focused in this area. I’ve taken considerable interest specifically in the southern Solomon Islands and the battles (both on land and sea) that took place in the surrounding area. When many people think of this region, immediate thoughts of Guadalcanal and the saga of the First Marine Division’s legendary fight (and “abandonment” by the U.S. Navy following substantial vessel losses on August 8-9, 1942 near Savo Island). When a WWII USMC uniform from a 1st MarDiv veteran became available (at an affordable price), I didn’t hesitate to pull the trigger on a purchase.

In stark contrast to the two Navy legends’ uniforms above, this nameless jacket was from a humble PFC of the 1st MarDiv.

Everything about this jacket is superb. Not a single moth hole and all of the buttons are present.

As a research project – trying to determine the service and experiences of the original owner – it possesses next-to-nothing that would afford me a path to pursue. The only identifying marks in the uniform jacket were three initials, “G. E. M.” The odds that I could pinpoint a veteran in the 1st Marine Division with those three letters makes the challenge daunting, to say the least. At this point, I haven’t had the time or desire to begin such an endeavor leaving the uniform to simply fill a space within my collection. I am happy just to own this uniform with the idea that this private first class Marine possibly served in one or more of the notable battles alongside the his brothers in The Old Breed.

To locate the uniform label (which contains the contract and date data) as well as identification marks left by the original wearer, check the inside of the left sleeve.

Immediately beneath the uniform label, the initials “G. E. M.” could correspond with the original owner’s name. Locating this marine would be next to impossible.

Related Uniform Topics:

All images are the property of their respective owners or M. S. Hennessy unless otherwise noted. Photo source may or may not indicate the original owner / copyright holder of the image.

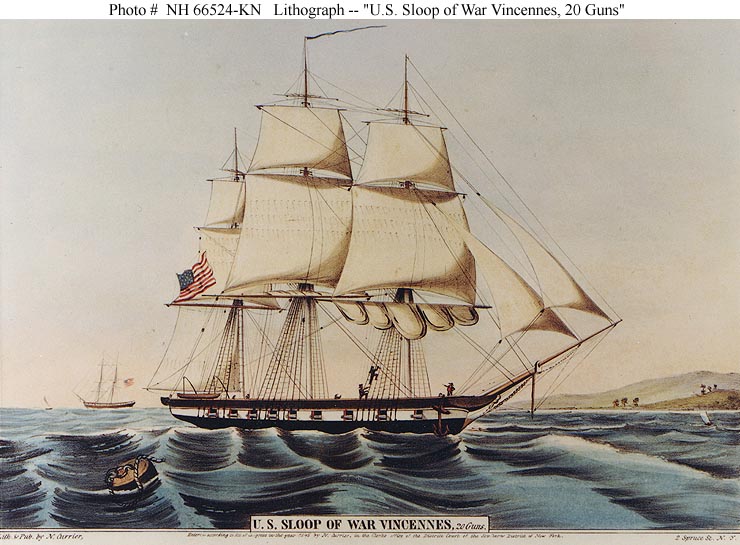

USS Vincennes Under the Microscope

Those who know me on a personal basis understand my affinity for a specific U.S. naval warship. Technically speaking, that interest lies with four combatant vessels, all of which were named to honor the site of a Revolutionary War battle (more accurately, a campaign) that ended the British assaults on the remote Western colonial front. That location in present-day Southwestern Indiana would later become the seat of the Northwest Territorial government in the town of Vincennes.

Colored lithograph published by N. Currier, 2 Spruce Street, New York City, 1845 (source: Naval Historical Center).

My connection to this ship’s name extends all the way back to the place of my birth which was also the location of the commencement of an extensive 1840 charting survey of Puget Sound (in Washington State). Locations and geographical features surrounding my home were named by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (commander of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842) and members of his team when the sloop of war, USS Vincennes (along with other ships of the expedition) was in the Sound. I can even cite some Baconesque connections with great, great, great-grandfather who served in the Ringgold Light Infantry (after he was discharged from his cavalry regiment following a disabling injury). The Ringgold name was inherited from Samuel Ringgold, Expedition-member Cadwalader’s older brother (yes, I realize that this is very convoluted).

My personal connection (to the ships named Vincennes) was solidly established when I was assigned to the pre-commissioning crew of the CG-49. During the first several months (leading toward the 1985 commissioning date), like many of my shipmates, I was exposed to the history of the ship’s namesake and established personal relationships with veterans of the WWII cruisers of the same name. Collecting items from “my” ship was purely functional in that I was proud to purchase t-shirts, lighters, ball caps and other items (from the ship’s store) that bore the name or the image of the ship’s crest. Many of the items I purchased in those days proudly remain in my collection while a few did manage to fade away.

I am constantly on the lookout for artifacts that are connected to these ships (the heavy cruiser: CA-44, the light cruiser: CL-64) and occasionally, some quality pieces (beyond the plethora of typical postal covers) surface on the market. Fortunately, I have been successful in obtaining a few of these items, though the competition has been fierce. The ones that got away were quite stunning.

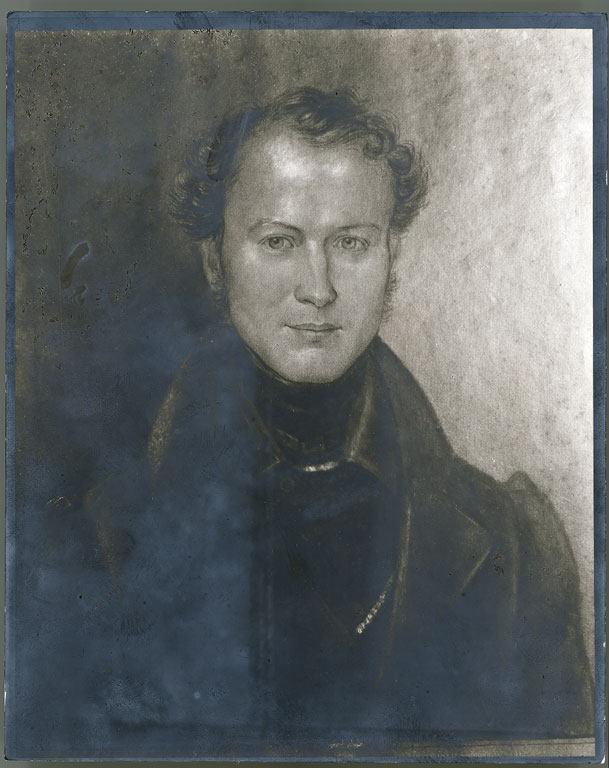

William D. Brackenridge was the assistant botanist for the U.S. Exploring Expedition serving aboard the USS Vincennes from 1838-1842.

The infrequency of appearances of pieces from the two WWII cruisers pales in comparison to anything related to the 19th Century sloop-of-war. During the past decade of searching for anything related to the USS Vincennes, I have only seen one item connected to the three-masted warship. While searching a popular online auction site, a rather ordinary, non-military item showed up in the search results of one of my automated inquiries. The piece, a wood-cased field microscope from 1830-1840, bore an inscription that connected it to the assistant botanist of the United States Exploring Expedition, William Dunlop Brackenridge.

Admittedly, I am not in the least bit interested in a field microscope as militaria collector, but the prospect of owning such a magnificent piece that would have been a fundamentally important tool used during the United States first foray into exploration was an exhilarating thought. At its core, the goal of the (1838-1842) U.S. Ex. Ex. was to chart unknown waters, seek the existence of an Antarctic continent and discover and document unknown species of flora and fauna. Brackenridge’s field microscope would have been a heavily used item as he and his assistants would most-certainly examine the various characteristics of plant species at a microscopic level.

The box appears to be missing some of the securing hardware which would help to hold the lid closed (source: eBay image).

Authenticity and provenance is certainly a major concern when purchasing a piece like this and the listing made no mention of any materials or means to verify the claim. However, in searching for similar microscopes, there was sufficient comparative evidence to support the time-frame in which the Brackenridge instrument was made. The box and the engraving seems to be genuinely aged and appears to resemble what one would find from a 170 year old example.

The box for the field microscope is inscribed with “Property of W. D. Brackenridge U.S.S Vincennes 1840″(source: eBay image).

In my opinion, the investment was well-worth the risk and I was poised to make my maximum bid (invariably draining my discretionary savings) knowing that the closing price would exceed what I could ultimately afford. The auction closed with the winning bid ($810.58) exceeding my funds by a few hundred dollars, though I suspect that the winner had a far higher bid in place to guarantee victory.

I am a realist yet remain hopeful that I won’t have to wait another decade before another sloop-of-war piece comes to market.