A Piece of Naval History or Just Macabre?

“The future naval officers, who live within these walls, will find in the career of the man whose life we this day celebrate, not merely a subject for admiration and respect, but an object lesson to be taken into their innermost hearts. . . . Every officer . . . should feel in each fiber of his being an eager desire to emulate the energy, the professional capacity, the indomitable determination and dauntless scorn of death which marked John Paul Jones above all his fellows.” President Roosevelt uttered these words (on April 24, 1906) within the confines of the United States Naval Academy at the re-interment of the of remains of the man who is known today as the father of the US Navy, Captain John Paul Jones.

Framing an artifact with historical context helps me (and hopefully readers of The Veteran’s Collection) to better understand the importance of an object or artifact. Rather than dive straight into an item, I find that setting the stage helps to provide perspective, so please bear with me.

As a militaria collector whose primary interest lies in US Navy artifacts, the idea of possessing anything from the Continental Navy is an aspiration that is almost too lofty to consider. The sheer scarcity of objects precludes ordinary collectors like me from pretense of forays into the Revolutionary-era collecting. Seeking out musket balls and powder horns from the Continental Army is one thing, but the minuscule number of patriot participants in the naval service (in comparison to that of the ground soldiers) equates to an incredibly limited volume of available artifacts for collectors.

Considering my financial position and the reality that just about any piece (that I would contemplate as being worthy of my interest) from the Revolutionary War is well out of my reach helps to keep me focused on artifacts that are both within my area of focus and budget constraints. However, on occasion, I do find myself wandering about through dealers’ internet sites and online auction listings from the 1775-1783 time-frame. Very seldom do I find anything that captures my attention which is something that happened not too long ago.

Engraving of the famous sea-battle involving John Paul Jones based on the painting “Action Between the Serapis and Bonhomme Richard” by Richard Paton (published 1780).

In school, we learned about the famous exploits of Captain Jones (born John Paul in Scotland in 1747, he added the surname Jones after emigrating to the Virginia Colony in the 1770s) with the notable sea battles between his ships and those of the Royal Navy. His legendary response to the surrender inquiry (“Has your ship struck?”) by the enemy commander of the HMS Serapis (Captain Richard Pearson), “I have not yet begun to fight!” will forever be cited in U.S. Naval lore. But most American school children are not educated on what became of Jones following his war service and his ultimate untimely demise.

Following the 1783 signing of the Treaty of Paris that brought about peace between Great Britain and the newly established United States, the need for maintaining a navy was lost on (most) congressional members. By 1785, the Continental Navy was disbanded and the last ship (Alliance) was sold off. Jones found himself in Europe (assigned to collect prize money on behalf of Continental Navy privateer sailors) without a command. After a short stint serving Empress Catherine II of Russia as an admiral in the Russian navy (along with some controversial legal troubles), John Paul Jones retired to Paris at the ripe old age of 45 in 1790. Two years later, the great Revolutionary War captain was found dead in his Paris apartment having succumbed to interstitial nephritis.

Jones was buried in the French royal family’s cemetery (Saint Louis Cemetery) with considerable expense to M. Pierre François Simonneau, who was incensed that the American government wouldn’t render the honors due such a national hero at his passing. Simonneau said that if America “would not pay the expense of a public burial for a man who had rendered such signal services to France and America” he would pay (the large sum of 462 Francs) himself.

With the collapse of the Louis XVI’s monarchy soon after Jones’ death and burial, the cemetery was sold and after a few years was largely forgotten. Decades passed and John Paul Jones’ grave was lost to decay and years of neglect.

In 1897, General Horace Porter was appointed as U.S. Ambassador to France by President McKinley. Soon after his arrival in Paris, Porter took personal interest in the pursuit of Jones grave while gathering official and private documents (much of it was conflicting) pertaining to his death and burial.

“After having studied the manner and place of his burial and contemplated the circumstances connected with the strange neglect of his grave, one could not help feeling pained beyond expression and overcome by a sense of profound mortification. Here was presented the spectacle of a hero whose fame once covered two continents and whose name is still an inspiration to a world-famed navy, lying for more than a century in a forgotten grave like an obscure outcast, relegated to oblivion in a squalid corner of a distant foreign city, buried in ground once consecrated, but since desecrated by having been used at times as a garden, with the moldering bodies of the dead fertilizing its market vegetables, by having been covered later by a common dump pile, where dogs and horses had been buried, and the soil was still soaked with polluted waters from undrained laundries; and as a culmination of degradation, by having been occupied by a contractor for removing night-soil.”

After years of research, Porter was confident that he had narrowed down the approximate grave site location. In 1905, excavation work commenced as archaeologists began digging beneath a building that had been constructed over the cemetery. Upon unearthing a third coffin (they knew that Jones had been buried in a costly lead casket), the men opened it and found a well-preserved body that matched all the details of the man they sought. Porter wrote, “For the purpose of submitting the body to a thorough scientific examination by competent experts for the purpose of complete identification, it was taken quietly at night, on April 8, to the Paris School of Medicine (École de Médecine) and placed in the hands of the well-known professors of anthropology, Doctor Capitan and Doctor G. Papillault and their associates, who had been highly recommended as the most accomplished scientists and most experienced experts that could be selected for a service of this kind. I of course knew these eminent professors by reputation, but I had never met them.”

- Still inside the dig site, workers pose with lead casket of what was believed to be the body of John Paul Jones.

- John Paul Jones in 1905. This is an official autopsy photograph taken of John Paul Jones’ corpse. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Naval Academy

- The 1780 bust of John Paul Jones by Jean-Antoine Houdon that was used in 1905 to positively identify the remains of John Paul Jones.

After careful examination, the physicians confirmed the identity (of the remains) as being that of the late Captain Jones. By August of 1905, the lead casket (which was placed inside a wooden casket) had arrived in the U.S. and was temporarily laid to rest at the US Naval Academy’s (USNA) Bancroft Hall during an April 24, 1906 ceremony. Jones’ body remained in this location while his final resting place was constructed beneath the USNA chapel. Upon completion of the elaborate and ornate crypt in 1913, the naval hero of the American Revolution was laid to rest at his final location.

- Casket of John Paul Jones is lowered to the deck of the USS Standish (U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.).

- Casket containing the body of John Paul Jones on the after deck of the Tug Standish, after its transfer from USS Brooklyn (Armored Cruiser # 3) in Annapolis Roads, off the U.S. Naval Academy, 23 July 1905. An honor guard stands around the flag-draped casket (U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.).

- John Paul Jones’ final resting place as it appears today (US Navy photo).

By now you might be wondering why I am going to such great length in describing what happened with the naval hero of the American Revolution and what the possible context is regarding militaria. While perusing an online auction site, I stumbled upon a listing pertaining to Captain Jones.

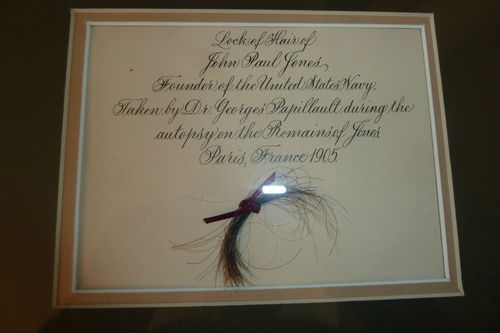

“RARE FATHER OF US NAVY JOHN PAUL JONES LOCK OF HAIR DOCUMENTED BY AUTOPSY DR” – Auction listing title

As I scanned through the various images detailing the different facets included with the piece it began to sink in that the auction lot was highly bizarre and extremely unique (if not macabre). Though seller made a minute attempt to fully describe what the item within the listing, he (or she) opted instead to let the incredibly small images (low resolution, no less) makeup for the lack of details within the text.

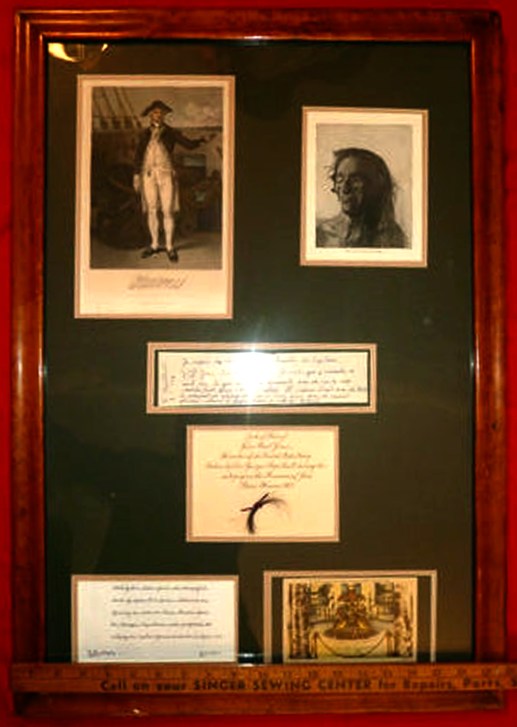

The rather large framed John Paul Jones group has the lock of his hair prominently displayed among the provenance and images (source: eBay image).

From appearances, the lot contained a lock of the Captain’s hair that had supposedly been removed by one of the physicians who performed the 1905 post-exhumation autopsy. Accompanying the lock (which was bound with a ribbon) was the doctor’s hand-written note regarding how he obtained the piece. Along with these two pieces is another handwritten note inscribed by the man who purchased the hair (“H. H. Strigley”) from the physician in January, 1926.

“Lock of hair of John Paul Jones, founder of the United States Navy. Taken by Dr. Georges Papillault during the autopsy on the remains of Jones. Paris, France 1905” (source: eBay image).

While this listing certainly piqued my interest, I’d shudder at the idea of forking over $3,500 (which I don’t happen to have available) without performing the necessary due diligence in verifying the documentation trail (or maybe a DNA test of the hair would be in order?). Taken at face value, the item would be a fantastic acquisition and quite the conversation piece for naval collectors.

- Preserved within the frame is the note from the original purchaser with his signature and the date (source: eBay image).

- Showing the orientation of the lock of hair, the original purchaser’s provenance note and the vintage postcard of Jones’ Naval Academy crypt (source: eBay image).

- The handwritten note from Dr. Georges Papillault, Assistant Director of the Laboratory of the Ecole des Hautes Etudes, professor in the school of anthropology (source: eBay image).

- Contextualizing the group are two images of John Paul Jones. One, an illustration of him during his naval service and the other, a photograph taken after exhumation, during his examination (source: eBay image).

- Also framed with the group is a vintage postcard of Jones’ crypt at the Naval Academy (source: eBay image).

- On the back of the John Paul Jones framed group is an attached envelope of supporting documents (source: eBay image).

While there is reason to question the validity of such an item, to the right collector, this John Paul Jones group would make a great investment. Perhaps the provenance documents are traceable and can establish enough proof (a hand-writing analysis of the note purportedly drafted by Dr. Papillault)?

An Open Invitation for Trouble: Risks of Sharing Militaria Collections Online

These named WWII Navy uniforms were passed down to me from my grandfather who served in the South Pacific.

Today’s post is a bit of a departure from my typical collecting discussion and is something that collectors should consider in term the various risks that exist as they share photos of their collections online. Some of those risks include:

- The family comes calling.

- Thieves trace their way to your collection in order to steal from you.

- Claims (false or otherwise) are made that your item does not belong to you.

- Image theft:

- Used for fraudulent militaria sales.

- Used without photo attribution.

Without belaboring every possible scenario, this post will focus on the four most common potentially negative outcomes.

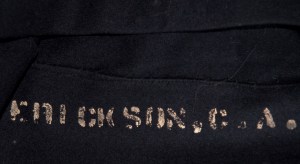

The Family Comes Calling

My collection is predominantly made up of uniforms that belonged to one of my relatives and the items were passed down to me due to my obvious interest in preserving family history. However, I have made some purchases of uniforms and other personal (named) items that belonged to veterans with no connection to me or my family. Uniforms are normally named (the service member placed identifying marks on the piece – normally on the manufacturer’s label or stenciled in a prominent location on the inside of the garment) with the troop’s last name, first and an initial and possibly their service number (there are variations and exceptions). When one goes as far as to share the identification details of a specific item online (as I did for articles such as, Militaria Rewards – Researching the Veteran and Academic Baseball Award: Rear Admiral Frank W. Fenno’s Baseball Career), I am risking someone reaching out to me to make a claim that the piece belongs in their family’s possession.

Virtually anyone can make a claim to the veteran’s items and state that they are the rightful heir of something that I purchased from a dealer, antiques store or private collector. Within our community there has been lengthy discussion surrounding what one should do if this situation is presented to them by a supposed family member. The stories (of the militaria leaving the family) are varied, ranging from theft to an heir not possessing interest in the military history (who sells the items rather than to pass them to another family member) to an unintended sale. It is easy to be sympathetic but that can be problematic for the collector as it is difficult to determine if the alleged family member is who they say they are (rather than another collector applying guilt and sympathy to get their hands on a desired piece). Here is a fantastic piece that was written regarding what family members should consider prior to contacting a collector in seeking the “return” of a family item.

With regards to the Admiral Fenno medal in the article listed above, I was contacted by a family member that was surprised to find that this medal was not in the family’s hands, let alone that it even existed. I was asked how it came to be in my hands (purchased from a picker who bought it at an estate sale) and speculated that the medal was sold along with other household belongings without any family members realizing what it was. The conversation was friendly between us as we exchanged a few emails. However, the person that I was communicating with wanted me to call them to chat about it further (which left me sensing that there was a request forthcoming). What I was thankful for was that the family member did convey additional history associated with the admiral that wasn’t available through research means. As of now, I am still hesitant to make the call as I don’t want to be asked to give it up. I suspect that the conversation could have been far more direct and uncomfortable between us so I am thankful with what I experienced.

Thieves Target Your Collection

I don’t actively worry about this possibility but I know that it happens. The general public may not realize the monetary value that many militaria pieces possess but people who lack moral compasses understand fully, what collectors are willing to pay for certain pieces. With WWII helmets that are attributable to veterans from well-known battles or engagements bringing sale prices in excess of $5-6,000, or a purple heart medal to a USS Arizona sailor who was KIA during the 7 December attack fetching double that amount, theft is a definite risk. I have read numerous news stories about break-ins and burglaries that involve the theft of militaria from homes. Not only are collectors at risk but veterans themselves are often subjected to these horrible actions:

- Local Marine’s military uniform and medals stolen Independence Day morning

- Former U.S. Marine says con man stole his military medals and uniforms

On occasion, there are successful recoveries:

- 24 military medals returned after being stolen during California dam evacuation

- Veteran’s Stolen Service Medals Returned

We have to be careful of who we invited into our homes being careful to limit visual access to these treasures when we answer the door to the furnace repairman, the plumber or the appliance technician. While they may be fantastic at their jobs, they might also be unwitting participants in tipping off burglars to the militaria inside your home. In addition, collectors need to consider how they share their pieces on social media. If they provide their real names and hometown locations in their public profiles, they could be providing a picking list and a treasure map to these seekers. If one shares their collection online, they should lock down their profiles and limit who can see personal details. Also, be cognizant of what is visible in the photos themselves for easily recognizable landmarks that can be used for locating.

Claims (false or otherwise) Attempting to Invalidate Collectors’ Ownership

In light of the previously listed risk, legally purchasing militaria can very well end up being an illegal transaction. In other words, you could be the recipient of stolen property. There are occasions that arise that upon sharing your collection item online, you face a challenge from someone claiming to be the legal and rightful owner. When one recognizes the flow of militaria from seller to buyer and that by the time it ends up in your own collection, it could have changed hands a few times. The piece could very well have been stolen from the veteran or a subsequent collector before the present owner received it. Imagine the thief selling the item to a picker who, in turn sells the piece at a flea market. That buyer then lists the piece on eBay where you, the collector purchases the piece in good faith. You proudly share your “score” with other collectors when you are contacted by the theft victim. What then?

As with essentially all collecting, the above scenarios are very real. What do you, the collector do? Imagine you paid thousands of dollars for the item? Do you simply surrender it to the victim? How do you know that this person is being honest? How can the claims being made be verified?

When a claim is made against your collection (be it the family, the veteran, a collector, etc.), the best action you can take is to be patient and consider the facts. Does the claimant possess photos of the item? Has a police report been filed (with a genuine case number) that matches the story? Did you record the details (dates, seller, price paid, etc.) of your transactions when you purchased the item? False claims are a part of this hobby and the unscrupulous folks thrive by preying upon good-natured, honest people (consider what happened to Phil Collins, the musician from the rock band, Genesis: Showing Off Your Collection is Not Without Risk). Collectors need to employ the same due diligence used to make sound purchases when these situations arise. I don’t profess to have the answers for every possible scenario but I am prepared as much as I can be to protect my investments.

Image theft

One of the risks that I want to focus my attention on surrounds the photography that we share of the items in our collections. I imagine that most people don’t consider the copyright protection that exist upon the creation of a photograph. Your photographs that you compose and capture belong to you whether you share them online or publish them in print. No one can reproduce (copy with their camera, grab a screenshot, etc.) without your permission (there are caveats to this and it can be a rather lengthy exploration of the laws and case law). One of the common actions that take place online, on eBay in particular, are the unscrupulous sellers who use other people’s photographs to defraud potential buyers by misrepresenting a similar item or selling taking money for an item that they do not possess and have no intention of delivering.

Another aspect of photo theft is that other collectors or hobbyists take your photos without asking or providing attribution. I have discovered use of my images in a few different manners ranging from a news outlet to sports bloggers (a few of my on-field sports photos were used for both without permission nor attribution). Fellow enthusiasts can also engage in these practices. In the recent months, I have discovered that one of my images of a Third Reich piece in my collection (I inherited it from a family member who served in the European Theater during WWII) has been used throughout the internet without my consent. The image was lifted from one of my Veterans’ Collection posts and has been used to illustrate this particular piece as it pertains to WWII German militaria. Understanding that it is quite a rare item, it doesn’t bother me (as much) when used in this capacity. When I found it being shared on an image-sharing site and being passed off as that person’s own work, it ruffled my feathers a bit.

The photo in question is of a Nazi Socialists Party Security armband that I also have hosted within my Flickr site:

National Socialist Party Security Personnel armband.

One of the sites where my image has been altered (they removed it from the background) has a massive online reference library of Third Reich armbands:

My armband photo has been altered and is listed as “NSDAP Ordnungsdienst Security” on the reference page without my permission.

There are several locations where I have found my photo being used sans permission. Seeing it displayed as another person’s property (they have it listed with “Some rights reserved”) is very infuriating:

Collectors must always be vigilant and cautious about how they share their passion with others. Using the internet as the vehicle for exposing your pieces and discoveries is very easy and may seem to be the safe pursuit, but there is no real insulation from those who would seek to do you or your collection harm.