Finding the “Lady Lex,” One Piece at a Time

A few weeks ago, our nation honored the 75th anniversary of the sneak attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7th. In the past few years, we have marked significant anniversaries of victories from WWII, the War of 1812 and this year we will begin recognizing the centennial of the U.S.entrance into the Great War. For collectors, these occasions spur us to evaluate our own collections while attempting to be discerning of sellers’ listings who are also trying to capitalize on the sudden interest.

In May of this year, 75 years will have elapsed since the first significant clash between the opposing naval forces of Japan and the United States in the Coral Sea. Leading up to this battle, the Navy had suffered losses in The Philippines, Wake Island and Guam followed by the sinking of the USS Houston (in the battle of Sunda Strait) all of which were leaving the U.S. extremely vulnerable and nearly incapable of mounting a naval offensive.

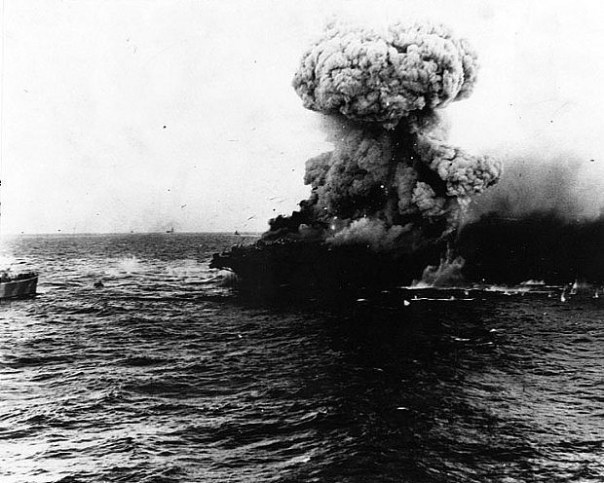

The Lady Lex is rocked by an enormous explosion during the Coral Sea battle, May 8, 1942 (Photo: Naval Historical Center).

USS Lexington (CV-2) provides electrical power to the City of Tacoma (WA) during a severe drought and subsequent electricity shortage – December 1929 – January 1930 (Photo: Tacoma Public Library).

Beginning with a joint effort between the US Army Air Force and the US Navy, the fight was taken to the Japanese home front with an B-25 air strike launched from the USS Hornet. But the direction of the war was seriously in doubt and Navy brass knew that inevitably, a direct naval engagement with the Japanese fleet were very near on the horizon.

Navy code-breakers had discovered the Imperial Japanese forces intended on taking Port Moresby in New Guinea and quickly dispatched Task Forces (TF) 11 and 17 to join up with TF 44 near the Solomon Islands and proceed West toward the Coral Sea. Over the course of May 3rd through 8th, the ensuing engagements between US and IJN forces resulted in substantial losses for both sides, including a carrier from each navy.

For the U.S. Navy, that carrier was the USS Lexington, CV-2. Though not the first purpose-built aircraft carrier (that distinction goes to the USS Ranger CV-4), Lexington was the first to be originally commissioned as a flat top. The Langley (CV-1) had a previous life as a collier, the USS Jupiter, for seven years from 1913 to 1920. The “Lady Lex”, as she would come to be known, laid down as a battle cruiser but was reconfigured during construction and was commissioned in 1927 as the US Navy’s second carrier, CV-2.

The result of the Coral Sea Battle was that the Navy was left with just two operational carrier: Hornet and Enterprise, as the Yorktown also suffered substantial damage in the battle requiring repairs. Less than a month later, the tables would be turned on Japan with the major American victory at Midway.

- A postal cover of the USS Lexington (Photo: Navsource.org).

- A leather squadron patch from the Early Knights of Bombing Two (VB-2) from the Lexington (photo: Brian’s WWII Surplus& Antiques Store)

- This SBD-2 Dauntless aircraft was recovered from a lake where it sat since 1945. While it was not a veteran of the Coral Sea battle, it did fly from the decks of the Lexington during the early months of 1942 (photo: National Naval Aviation Museum)

- This plotting board was used by Lieutenant (junior grade) Joseph Smith during the Battle of the Coral Sea when, while on a scouting mission from the carrier Lexington (CV 2), he spotted Japanese aircraft carriers and their escorts (photo: Naval Aviation Museum).

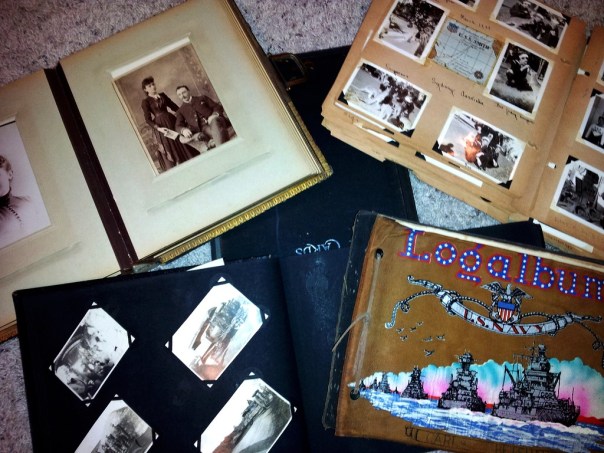

- A sailor’s leather-bound USS Lexington CV-2 Photo album (photo: eBay).

The loss was not only felt by her crew and navy strategists, but also by communities, such as Tacoma, Washington. For 31 days during winter drought conditions, the Lexington was sent to aid the city’s citizens by generating power ’round the clock, helping to keep their homes lit and warm. Many of those beneficiaries of the electrical power assistance were devastated by the news of her loss.

Today, few artifacts remain from the Lady Lex. Militaria collectors would be hard-pressed to obtain anything specific to the ship, instead having to settle for obtaining USS Lexington veterans’ personal effects or uniform items, surviving ephemera, philatelics, or vintage photographs. For many naval collectors, the hunt for anything from this historic ship can very rewarding. Some artifacts can be found by happenstance as was the case with this Curtiss SB2C Hell Diver, recently pulled from the Lower Otay Reservoir near San Diego, discovered by a fisherman who observed the plane’s outline on his fish-finder.

Armed with patience and time, collectors could assemble a nice group of artifacts to pay proper respect to the Lady Lex and the men who served aboard this historic ship.

UPDATE March 5, 2018: Paul Allen’s Undersea Exploration team that has been searching and discovering the wrecks of the Pacific War, finding such infamous sunken vessels as the USS Indianapolis and the lost ships from the Battle of Savo Island (USS Vincennes, Astoria and HMAS Canberra), announced today that they have located and filmed the wreck of the USS Lexington (CV-2) at the bottom of the Coral Sea in nearly two-miles of depth.

Collecting on a Short Fuse

When I embarked on my quest to gather facts and information about my ancestors’ service to this country, I never intended to become a collector of militaria. In acquiring and assembling uniform items for these visual recreations, I found myself the recipient of some odd pieces that would, at the very least, raise some eyebrows. At worst, I could blow myself and my home to pieces (well, not really…read on).

75mm Artillery round with Model 1907 M fuse.

Last week, I posted about inheriting some vintage military edged weapons. Along with the various fighting knives, swords, bolos and bayonets, I was a given the opportunity to take home two objects that were quite different from everything else in my family member’s collection. The two objects had been displayed alongside the wood stove, exposed to considerable long-term heating and cooling for many years. By now, some of you might have realized that I am referring to artillery rounds.

As I’ve stated in previous postings, I am by no means an expert in all things militaria. However, my research skills certainly provide me the means to identify the artillery items. With common sense as my guide, I knew enough that I wanted to ensure that the items were inert – meaning “not live or possessing any explosive capabilities.”

Prior to handling any ordnance it is HIGHLY recommended that collectors have verification of the inert status of the item. There are some good resources online that can provide collectors with guidance prior to making the leap into this highly specialized area of militaria.

- Introduction to Collecting Artillery Shells and Shell Casings

- Collecting Ammunition and Explosive Ordinance

- A Guide to Ammunition Collecting

- This box of .45 cal pistol ammo is in pristine condition.

- This box of .45 cal. pistol rounds is from World War II and is very much live.

There are many examples where live ordinance was discovered in homes, brought home as souvenirs of service and left behind, to be discovered by family members or new occupants of the residence. Imagine the horror of the discovery learning that the item was live. This happens quite often as indicated by the countless news articles available online. Here’s a sampling:

Along with brass and other empty shell casings that I managed to save from my time on active duty, these pre-World War One artillery pieces are a nice complement to my collection:

- Showing the detached (inert) fuse from an M1907 75mm pre-WWI artillery round.

- I haven’t identified this artillery fuse yet. I do know that it is inert.

The Blades That Got Away

Is there truly such a thing as being too greedy? Can someone be overcome with coveting? I am certain that the pursuit of objects (of my desire) is a pathway that I should try to avoid (or, at the very least, make a concerted effort to avoid), but in some cases, the end result is a boot print in your own derriere after passing on the opportunity to acquire a beautiful piece of militaria.

Sadly, I only have photos of the Model 1860 Cavalry Sword’s handle.

A few years ago, a relative of mine who was a militaria collector (specifically, Civil War) passed away after a lengthy illness. At the time of his passing, his collection included Spanish-American War rifles, post Civil War belt buckles, and an assortment of edged weapons spanning more than 100 years and representing multiple branches of service.

Knowing that I have a passion for military history and military collectibles, though I am by no means an expert, my family asked for my assistance in identifying certain items and assessing values for the estate. Notebook, pen and Blackberry (with a built-in, crummy low-resolution digital camera) in hand, I made my way over to my relative’s home to begin my work.

Prior to my arrival, all of the militaria pieces had been gathered (piled) into one of the rooms and I was immediately overwhelmed by what was there. Separating the items I could easily identify from those that needed research, I began to document and inventory everything. I knew that because of the assistance I was rendering, I’d have the first opportunity to purchase anything that interested me, should the beneficiary choose to sell.

Diving into the edged weapons, I quickly jotted down the details – M1904 Hospital Corps bolo, M1910 Bolo Machete,M1913 Patton Sabre, WWII USMC Pharmacist’s Mate Bolo, many types of bayonets… the list went on. The two pieces that really caught my attention were very old. One, an M1832 Foot Artillery sword and a Model 1860 Cavalry Trooper’s sword. Both were in pristine condition.

I went home and did my research, comparing the photos I snapped against those of the various online and printed references. Adding up the blades and the corresponding values, I set aside the funds in order to pay for the ones I wanted and submitted the work to the estate. I intentionally left off the two oldest blades as I my budget couldn’t accommodate those high-dollar (for me) purchases.

Showing the eagle in the Ames Model 1832 Artillery Foot Sword. This one is dated 1840.

A few months later, the blades that I was seeking to acquire were delivered to me as a gift. The other pieces that I turned away were sold – for pennies on the dollar – to the estate sales company that was contracted to liquidate the personal property. I was heartbroken. The two blades that I really wanted for my collection were sold at such a low price, I could have easily paid for them even if I was required to buy the blades that I had been given.

Because I chose to collect within my means, someone else benefited and made a killing on these two blades. I will think twice before I make this decision again.

A Thousand Words? Pictures Are Worth so Much More!

As my family members have passed over the past several years, I have managed to acquire a number of antique photo albums and collections of photos of (or by) my family members that nobody else wanted. Most of the images’ subjects were of family gatherings, portraits or nondescript events and contained a lot of unknown faces of people long since gone. As the only person in the family who “seems to be interested” in this sort of history, I have become the default recipient.

Here is a sampling of vintage photo albums I’ve inherited.

My Hidden Treasure

With all the activities and family functions occurring in my busy life, those albums received a rapid once-over (to see if I could discern any of the faces) and then were shelved to gather dust as they had done with their previous owners. Years later, I began to piece together a narrative of my relatives’ military service (a project you will hear about over the course of my blog posts). I have since returned to those albums only to discover a small treasure of military-related images that are serving to illustrate my narrative project. As an added bonus, they are providing me with an invaluable visual reference as I am reconstructing uniform displays to honor these veterans.

Photographs Can Unlock the Secrets

Similarly, militaria collectors strike gold when they can obtain photo of a veteran in uniform that can help to provide authentication as part of the due diligence for a specific group they are investigating prior to an acquisition. A photo showing the veteran wearing a certain Shoulder Sleeve Insignia (SSI), ribbon configuration or even a specific uniform garment can be authenticated if there are visible traits (such as tears or repairs) within the image.

Photographs from GIs in a wartime theater of operations or in combat are fairly rare. Photography was outlawed by theater commanders (due to the obvious security risks if the film or photographs were captured) and space was at a premium as one had to pack their weapons, ammunition, rations and essential gear. So finding the room to safely carry a camera and film for months at a time was nearly impossible. Similarly, shipboard personnel were not allowed to keep cameras in their personal possessions. Knowing the determination of soldiers, airmen and sailors, rules were meant to be broken and, fortunately for collectors, personal cameras did get used and photos were made while flying under the censors’ radar.

If you have deep pockets and you don’t mind paying a premium for pickers to do the legwork, wartime photo albums can be purchased online (dealers, auction sites) for hundreds of dollars. Many times, this can be a veritable crap-shoot to actually find images that have significant military or historical value and aren’t simply photos of an unnamed soldier partying with pals in a no-name bar in an an unknown location. For militaria collectors at least, there is value in the image details.

As you obtain military-centric photos, take the time to fully examine what can be seen. Don’t get distracted by the principal subject – look for the difficult-to-see details. Purchase a loupe or magnifying glass to enable you discern the traits that can reveal valuable information about when or where the photo was snapped. What unit identifying marks can bee seen on the uniforms? Can you identify anything that would help you to determine the era of the uniforms being worn by the GIs?

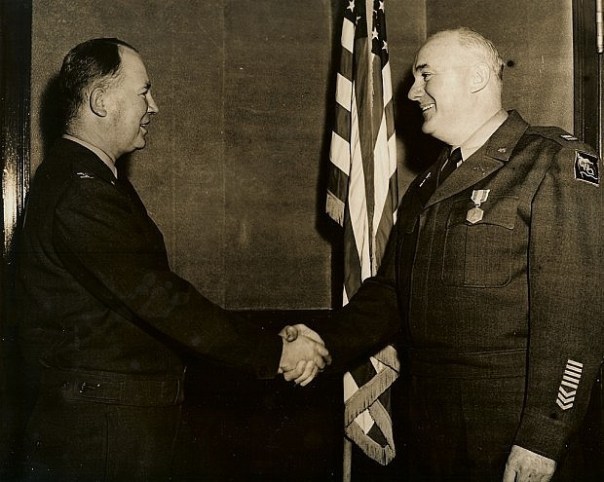

My Own Success

In assembling a display for one of my relatives, I wanted to create an example of his World War I uniform because the first of his three wars was quite significant in shaping his character for his lifetime. Having already obtained his service records (which span his entire military career, concluding a few years after the Korean War), a book that was written about his WWI unit (published by a fellow unit member) and my uncle’s photo album which was filled with snapshots of his deployment to France, I figured I would be able create a decent uniform representation.

- In this image, you can’t quite make out the left shoulder insignia.

- A close-up of the left shoulder revealed the SSI of the 1st Army (artillery branch).

- This photo shows my uncle (on the left) in France with his First Class Gunner rank insignia.

- In the close-up, you can (almost) clearly make out the rank insignia of a First Class Gunner.

An overview of the uniform (and overseas cap) that I have recreated to represent my uncle’s WWI service. Note the artillery shell insignia on the right sleeve is that of a First Class Gunner.

In the various photo album images, I could see his right sleeve rank insignia as well as the overseas stripes on his left sleeve quite clearly. I could even make out his bronze collar service devices or “collar disks” in the photos (since I had his originals, they weren’t in question), but I had no idea of what unit insignia should go on his left shoulder. Not to be denied, I took the route of investigating his unit and the organizational hierarchy, trying to pinpoint the parent unit to which the 63rd Coastal Artillery Corps was assigned. Having located all of that data, I was still unsure of the SSI for the right shoulder.

Temporarily sidetracked from the uniform project, I returned to the photo album and scanned a few of the images (at the highest possible resolution) for use in my narrative. With one of the photos, I began to pay close attention to the left shoulder as I zoomed in tightly to repair 90 years worth of damage…and there it was! At the extreme magnification, I could clearly see the 1st Army patch (with the artillery bars inside the legs of the “A”) on my uncle’s left shoulder. I had missed it during the previous dozens of times that I viewed the photo.

An overview of the uniform (and overseas cap) that I have recreated to represent my uncle’s WWI service. Note the artillery shell insignia on the right sleeve is that of a First Class Gunner.

A close up of the SSI of the 1st Army (with the red and white bars of the artillery), my uncle’s collar disks, the honorable discharge chevron and his actual ribbons.

My research now complete, I obtained the correct vintage patches and affixed them to an un-named vintage WWI uniform jacket along with my uncle’s original ribbons and collar devices (disks) to complete this project. Now I have a fantastic and correct example of my uncle’s WWI uniform to display.