Category Archives: Military Weapons

Collecting Militaria: Historical Preservation or War Glorification?

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.”*

I started this blog as a continuation of a similar effort that I undertook (as a paid gig) for a large cable television network. I spent some time contemplating a suitable name for this undertaking, settling on The Veteran’s Collection for a number or reasons. The simplest of those reasons was to express my interest in militaria and how my status as a veteran guide both my interests and desire to preserve history.

Though my wife might argue, my collection of patches is rather small as compared to those of true military patch collectors. I tend to be more specific about the patches I seek (such as this USS Tacoma crest edition).

Often, I equate my collecting of military items in the vein of being a curator of military history and the role that the military has played in the securing and preserving of basic freedom for our nation (and for the people of other nations who have been trying to survive under repressive regimes). In gathering and collecting these items, it may appear to some that I am glorifying war. Having in my possession weapons (firearms, edged weapons, munitions, etc.) might signify glorification to the untrained eye however these items are part of the overall story being conveyed by collection.

As I scour my collection, I begin to realize that the overwhelming majority of items are Navy-centric. This 1950s U.S, Army cap is part of the display that I am assembling of my paternal grandfather’s older brother’s service.

I am a fairly soft-spoken person when I am out in public (though people who truly know me would have a difficult time believing this). When political conversations emerge near me (when waiting in line or casually walking past strangers in public settings) I have heard, on many occasions, discussions focus on perceptions of men and women who serve ( low-key or have served) in the armed forces. Often times, gross mis-characterizations regarding people in uniform begin to emerge as the dialog devolves into denigration of active duty and veterans as being war-hungry criminals, bent on killing innocents (women and children). I can’t count how many times I have stood in line, listening to people in front of me expressing how frustrated they are when they see a soldier in uniform ahead of them receiving a discount for a food item or service equating their time in service as legalized murder.

I served ten years on active duty and had two deployments into a combat theater, one of which I and my comrades were engaged by the enemy. In all of those ten years, I cannot recall a single person whom I served with who desired or wished to see combat. We prepared and trained for it hoping to never see it. I don’t think that I have ever met a combat veteran who wanted to talk openly about their time under fire. To have the uneducated civilian boil down our willingness to don the uniform, train for years while understanding fully that at some point during our service, we could see the horrors of combat as being blood-thirsty war-mongers only serves to show the extent of their ignorance.

I recently read two articles today concerning veterans of World War II who have (or had) committed their remaining years educating people about the horrors of war that each of them faced.

The first article was about one man, an IJN fighter ace Kaname Harada, who took every moment that he had left in order to do what the Japanese government is failing to do; educating younger generations to warn them about being drawn into future wars. “Nothing is as terrifying as war,” he would state to an audience as he spoke about his air battles from Pearl Harbor to Midway and Guadalcanal. As I read the article, I zeroed in on a chilling quote by one of Harada’s pupils, Takashi Katsuyama, “I am 54, and I have never heard what happened in the war.” He cited not being taught about WWII in school, continuing, “Japan needs to hear these real-life experiences now more than ever.” I am baffled that a man who is a few years older than me was not taught about The War in school.

In the second article, Army Air force fighter pilot, Captain Jerry Yellin, who like Harada, is educating young people about what he sees as futility of war. He is concerned that young Americans do not have an understanding of the realities of war nor what it is like to fight. “We’re an angry nation,” said Yellin. “We’re a divided nation: Culturally, monetarily, racially and religious-wise we’re divided.” What the veteran of 19 P-51 missions over Japan said (in another article) regarding war is often lost on those who are pacifists (at any and all costs) and lack understanding, “War is an atrocity. Evil has to be wiped out.” He continued, “There was a purity of purpose, which was to eliminate evil. We did that. All of us. So, the highlight of my life was serving my country, in time of war.”

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana

Both of these men clearly understand the cost of war and the hell that they faced when they took up arms and yet neither of them could be characterized with the ridiculous “war mongers” moniker often applied to warriors.

The reasons that people collect militaria are as diverse as each of the hobbyists’ backgrounds. The community of collectors can be completely aligned and in lock-step with each other on some militaria discussion topics and in near animus opposition on others. I tend to stay away from collecting medals and decorations; specifically, anything awarded to a veteran (or, posthumously to his family) due to how a great number of collectors commoditize certain medals (Purple Heart Medals, specifically). I withhold judgment as I abstain from even discussing the medals in question. For the laymen, a Purple Heart is awarded to service members wounded or killed in action. Collectors attach increased value for medals awarded (engraved with the recipient’s name) for posthumous medals; if the person is notable or was killed in a famous or infamous engagement, the value compounds (there are several other contributing factors that influence perceived monetary value).

- This is the Western Union telegram that was delivered to PFC Skavinsky’s wife, notifying her of his death. It took 10 days to get word to her. (Source: PurpleHearts.net)

- The Purple Heart Medal (photo source: PurpleHearts.net)

- The back of Skavinsky’s Purple Heart shows the official engraving of his name (Source: PurpleHearts.net)

- PFC Skavinsky’s accompanying certificate documenting the awarding of the medal and the date in which he was wounded. (Source: PurpleHearts.net

Purple Heart Medals are a very sensitive area of military collecting and nearly every medal was awarded to combat veterans – soldiers, marines, sailors and airmen who were serving in a war or wartime capacity. There are several collectors who use their Purple Heart collections to demonstrate the realities of the personal cost of war. These caretakers of individual history, such as this collector, painstakingly preserve as much of the information surrounding the WIA and KIA veterans, often maintaining award certificates and even the Western Union telegrams that were presented to the recipients’ parents or widows. Seeing a group with the documentation together is heart-wrenching.

A few of the selected items that my uncle brought back at the end of the war in Europe.

Militaria collecting can be very personal as many of the items, like medals (such as the Purple Heart) actually belonged to a person who served. In my collection, I have uniforms from men who served from as far back as the early 1900s up to and including the Vietnam War (not including my own as seen in this previous post) with the majority centered on World War II. Nothing could be more personal than the uniform worn by the veteran. Having personal items, in my opinion, enhances the collecting experience because of the desire to research what that service member did when they served. Uncovering a person’s story is to understand the sacrifice and cost of leaving family behind to serve rather than glorifying war itself.

Also in my collection are artifacts that were brought back by the veterans from the theater in which they served. While to some people, viewing these items may conjure negative and visceral responses, they still serve to tell a story that shouldn’t be forgotten. One of my relatives returned from German having recovered a great many pieces from the Third Reich machine after it was defeated by May of 1945. Still, this is not celebrating war nor the defeat of a (now former) foe.

There are other facets of my collection that are touch on the functions of engagement and combat; specifically armament and weapons. I have a few pieces that I inherited that, at some point, I will be delving deeper (on this blog) as they do fascinate me. I need to spend some time expanding my knowledge a bit more in order to present these pieces with a modicum of understanding (alright, I’ll admit that I don’t’ want to sound uneducated on my blog). Frankly, weapons are not my forte’ but what I own (a small gathering of edged weapons and ordinance), I have spent some time learning about them.

- I have a smattering of edged weapons (or, in this case, an edged tool) that I mostly inherited. This bolo knife was carried by Navy Pharmacists Mates (a.k.a “corpsmen”) who were attached to USMC units. The “U.S.M.C” embossed on the blade represents the United States Medical Corps.

- M1917 U.S. Military bolo knife and scabbard.

- 1942 M1 Garand Bayonet

Preserving history is paramount to helping following generations to both understand the cost of war and that, while doing what is necessary to avoid future wars, serves to illustrate that nations not only should but must take a stand against tyranny and evil.

See also:

* Military Memoirs of a Confederate, 1907, Edward Porter Alexander

Shadow Boxing – Determining What to Source

(Note: This is first installment of a multi-part series covering my research and collecting project for one of my ancestors who was a veteran of the American Civil War)

- Part 1 – Shadow Boxing – Determining What to Source

- Part 2 – Civil War Shadow Box Acquisition: “Round” One is a Win

- Part 3 – Due Diligence – Researching My Ancestor’s Civil War Service

- Part 4 – Boxing My Ancestor’s Civil War Service

This bullion cavalry hat device could be a centerpiece and would look fantastic in a display (source: Mosby & Co Auctions).

For me, collecting militaria has been an adventure of discovery as I learn about who my ancestors were and what they did to contribute to the freedoms we enjoy in the United States today. As I’ve stated in earlier posts, my research began with the receipt of a handful of militaria pieces and documents for two of my relatives who served in the armed forces.

Rather than simply store the items in a drawer or closet, I wanted to assemble and display them in such a manner as to succinctly describe their service. Seeking to be as complete as possible, I sent for the service records for both relatives so that I could fill in the gaps if there were any missing decorations from what I already possessed. Upon receipt of the records from the National Archives, I noted that there were, in fact, several awards that had never been issued to either veteran (many service members were discharged at the war’s end war, prior to the decorations being created and subsequently awarded) and promptly obtained the missing pieces.

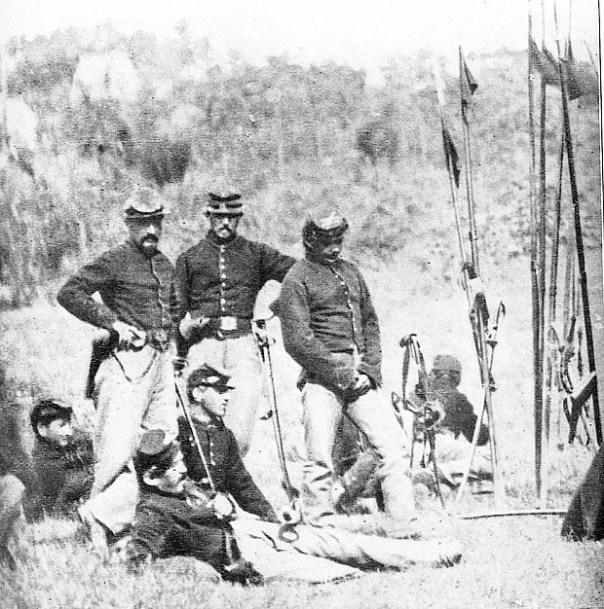

“I” Company of the famed Rush’s Lancers. Photos like these go a long way to help collectors seek the correct items for accurate displays. This photo was taken by Matthew Brady.

In preparation for assembling the displays, I was motivated to learn all that I could about others in my family who served. As I worked on my family tree, I began to discover that there were veterans at each successive prior generation who served. From Vietnam to the Korean War, World War II to the Great War, from the Civil War, the war of 1812 and finally, the American Revolution, I had ancestors who were participants. At the prompting of my kids’ inquiries as to who these people were and what they did, I embarked on a mission to assemble tangible representations of some of the notable veterans in the family lineage – including uniform items, awards and decorations.

This is a close-up of the soldiers of “I” Company, 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry. This photo was taken by Matthew Brady and clearly shows the weapon that gave the regiment its name.

Limited by financial resources and storage space, I needed to choose the people from our past that would garner my collecting attention. This decision has caused me to abstain from purchasing some of the items that I found very interesting but couldn’t justify acquiring (after all, I am not creating a museum in my home).

One of my recent discoveries is that veteran in my lineage served in a storied regiment during the American Civil War. This unit, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was the only mounted regiment to be equipped with the lance as their primary weapon, prompting the nickname of Rush’s Lancers (Lt. Colonel Richard Rush was the unit’s first commanding officer). While my ancestor wasn’t a distinguished veteran or officer (he was a corporal), he did serve throughout most of the war, participating in many of the bloodiest battles.

Well out of my budget, this Lance (that was carried by a member of Rankin’s Michigan Lancers) during the Civil War, sold at auction for $1,440.00 a few years ago (Source: Cowan’s Auctions).

I have been pondering how I could create a tasteful, yet small assembly of items that would provide an authentic and visually appealing display. What sort of items are available (and that I could afford) that would fit into a smaller shadow box and tell a story of my great, great, great grandfather’s service?

- This .44-caliber slug could provide a measure of authenticity in my display as the revolver was carried by the troops or the 6th Penna. Cav. If this were dug from one of the Lancer’s battlefield sites, it would only make the display that much more personal (Source: Civil War Outpost).

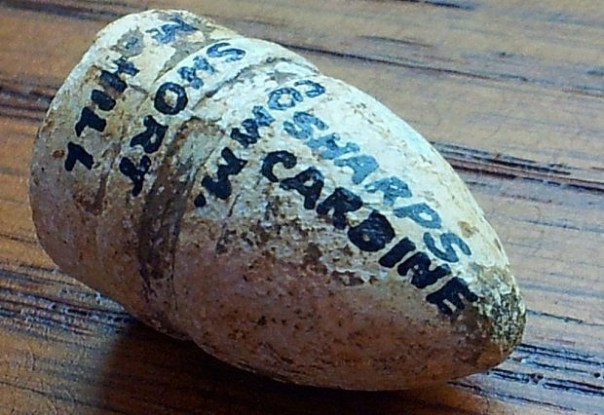

- After shedding the lances, the 6th Penna Cavalry switched to the more traditional weapons. This .52 caliber Sharps carbine round would be appropriate for my display (source: Greg’s Relics).

While this cavalry button (as distinguished by the “C” on the eagle’s shield) may be accurate for a cavalryman, it isn’t appropriate for my ancestor’s display as he was a corporal. I am still researching the proper buttons for display to confirm my suspicions, but I may be faced with purchasing the extremely rare Pennsylvania-specific buttons – as Rush’s Lancers were not a mainline Union Army regiment.

Taking into account that my relative was a member of the Union Army, I could pursue pieces of the Union uniform such as buttons or other devices. I would need to focus on cavalry as their buttons are different from those of the infantry. If I was fortunate enough to locate one at a reasonable price, I could obtain the kepi hat device. Including excavated items such as ammunition rounds for weapons carried by cavalry (such as .52- or .56-caliber carbine or .36- or .44-caliber revolver rounds) that were found on one of the unit’s battlefields would be a terrific accent to the display. Ideally, I’d like to get my hands on the blade from a lance, but with the lofty price (one was sold at auction in 2005 for $1,440.00) they command, I will have to abstain. If I can locate a period-correct Civil War medal, it would be icing on the cake.

No matter the direction that I ultimately decide to take, I know that I will be spending the next several months scouring the online dealers and auction sites to acquire the pieces. In the meantime, I await my great, great great grandfather’s service records so that I can (hopefully) nail down his service and create an accurate display.

Continued:

Civil War Shadow Box Acquisition: “Round” One is a Win

- (Note: This is second installment of a multi-part series covering my research and collecting project for one of my ancestors who was a veteran of the American Civil War)

- Part 1 – Shadow Boxing – Determining What to Source

- Part 2 – Civil War Shadow Box Acquisition: “Round” One is a Win

- Part 3 – Due Diligence – Researching My Ancestor’s Civil War Service

- Part 4 – Boxing My Ancestor’s Civil War Service

Yesterday’s mail delivery netted for me my initial foray into American Civil War artifact collecting. I like to counsel would-be militaria collectors to focus on their collecting – choose a specific area of interest and pursue that area. While I have been trying to live and collect by this guidance, to the casual observer it would appear that, with this purchase, I have altered my stance.

My collecting focus has been centered upon one thing: creating displays or groups that provide a visual reference of specific veterans in my family and honor their service. That direction has predominantly led me to twentieth century militaria collecting as the items would pertain to those individuals’ service. Another contributing factor has been the affordability and abundance of World War II militaria. It has been a bit more challenging to assemble artifacts from the Great War.

Showing the beautiful labeling on the .52 caliber Sharps Carbine round acquired for my shadow box display.

The package that was delivered to my door yesterday was small and weighed very little and yet this item would be one of the central pieces in my small display dedicated to the service of my great, great, great grandfather. In researching him and discovering certain details of his service, I decided that I wanted to assemble some significant artifacts for a shadow box that would provide subtle.

Understanding that my 3x great grandfather served in a cavalry unit, I began to research the engagements they participated in. While I am still waiting for my ancestor’s service records, I made some safe assumptions as to which specific campaigns and battles that he participated in, following his regiment and company’s history. Armed with those details, I began to search for anything that could be closely connected to him. Having researched the weaponry, I determined that he would have carried a Sharps Carbine by the time his regiment participated in the battle at Malvern Hill and used that information to search for specific artifacts.

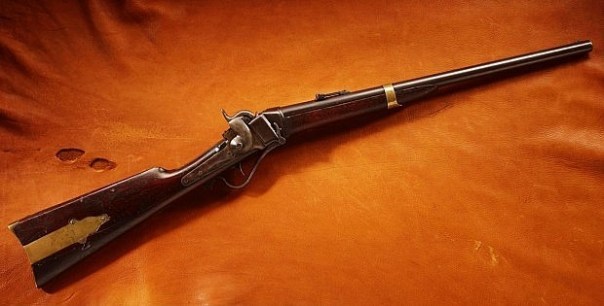

This Model 1859 Sharps “New Model” Carbine .52 Cal rifle was the principal weapon for the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry – once they shed their lances (source: National Firearms Museum).

My search led me to several choices of “dug” artifacts, many of which were in my budget. I honed in on one specific bullet round, a .52 caliber “New Model” Sharps Carbine round that had, more than likely, been dropped on the battlefield. The round is beautifully labeled with details about where it was found and what it is and it came from the collection of a known Civil War expert. Feeling safe about the item, the seller’s history and the aesthetic qualities, I went ahead with my purchase.

For the remaining items, I will continue to be patient and educate myself before I pull the trigger (pun intended).

Continued:

To Whom do Artifacts Truly Belong?

This cigarette box is engraved with the names of four WWII naval aviators (engraved” Best Wishes to The Torpedo Captain”). Though this piece is in my collection, as a collector, I am merely a steward of the history associated with it.

Historians, museum curators, historians and collectors all have differing, yet valid answers to the question of historical artifact ownership. Aside from the debate as to where an artifact belongs, there can be difficulties for collectors surrounding rightful ownership that can have more nefarious roots and beginnings.

While watching an episode of the popular PBS television program History Detectives, a woman desired to learn more about a boxed set of named (inscribed) mid-19th century Derringer pistols (season 10, “Civil War Derringers, KKK Records & Motown’s Bottom Line”) that her father purchased in the 1970s. The woman had previously had the Derringer set appraised on another PBS show, Antiques Roadshow (Pittsburgh #1607) for $30,000 but she had no idea who the original owner was or any details surrounding the history of the pistols. Included with the pistol was a document detailing the post Civil War pardon of a Confederate soldier – the name matched the one inscribed on the pistols.

The “detective,” Wes Cowan embarked on a quest to learn about the original owner (John P. Thompson) and if he was, in fact, a Civil War veteran and to learn his history if at all possible. The trail that Cowan followed ultimately led to the great, great-granddaughter of John C. Thompson who told the story of her ancestor and how the pistols were stolen from the ancestral home in the 1970s. To whom do these pistols belong?

My entrance into militaria collecting began more as a matter of happenstance rather than an active pursuit. Having a passion for local area history and genealogy began for me at an early age. As a child, I would often imagine myself digging up arrowheads or other historical artifacts while digging in the backyard or the adjacent vacant lot. Sparked by my grandfather’s stories of the “Indian Uprising” in present-day Pierce County (the father of his childhood friend told him stories of their family evacuating to the safety of Fort Steilacoom), I would picture myself finding my own piece of history.

I never pursued any real archaeological adventures as my focus shifted toward sports and other adolescent activities. After completing my schooling, I was thrust back into history but this time with a military focus when I was assigned to my first ship (following boot camp and my specialty school). I was immersed into the legacy that led to the naming of my (then) soon-to-be commissioned U.S. Navy cruiser. I began to dialog with the veterans of my ship’s namesake predecessors from WWII. From that point on, my interest in military history was truly piqued.

This sampling of Third Reich militaria items were passed down to me from my uncle (who served in the U.S. Army MIS/CIC). He sent these peices home from Germany in 1945 having liberated them following the collapse of the Wehrmacht.

Collecting, for me, began when I was asked to bring my interests and research skills to bear on some artifacts belonging to my uncle that had been stored for 50 years in my grandparents’ attic. The items were in a few trunks that were unopened since they were packed by my uncle and shipped from Germany in May of 1945. I knew very little about Nazi militaria but was up to the challenge to ascertain value and locate a buyer (my grandparents needed money to help cover their costs of care) for the artifacts. I spent a few months learning about the various uniforms, flags, headgear and badges. Little did I know that I was being immersed into the world of the high-dollar Third Reich collecting (yes, I sold most of the pieces).

My uncle served in three wars (WWI, WWII and the Korean War) rising from private to captain. This uniform and bag are from his service with Battery F the 63rd of 36th Coast Artillery Corps.

A few years later when I received my maternal grandfather’s uniforms, records, medals, ribbons, etc., I began to understand that while these items are in my possession, they really do not belong to me. I am merely safeguarding and preserving them for posterity. This has become more evident during my search for anything relating to my ancestors who served in previous centuries. I often wonder what became of their militaria. In watching the History detectives episode, my concern for lost family history is decidedly more acute as I have yet to locate a single photo (of my lengthiest pursuit – my 3x great-grandfather who served in the Civil War).

Recreating History: Researching and Assembling an Ancestor’s Civil War Artifacts:

In actively pursuing items now in my collection, I have acquired a handful of pieces that have names inscribed or engraved of their original owners. The thought has occurred to me that the potential exists for a descendant to claim rights to anything that bears a name.

People fall on hard times or may not possess interest in the military history of their ancestry. A financial need or the desire to free up storage space can drive people to divest themselves of military “junk” without pausing to realize their own connection to that history. In some cases, the heir of militaria may pass away severing ties to the historical narrative thereby devaluing it entirely.

While one person (family member “A”) could have inherited an ancestor’s militaria and subsequently opted to sell, another relative (family member “B”) might have not have been provided the opportunity to retain the history within the family. I have seen stories of this scenario playing out where family member “B” notices a post by a collector (in an online militaria forum) about something recently acquired. “B” feels the need to reach out to the collector to restore the item back to the family, often times to the point of accusing the collector of being a party to theft.

I can identify with the plight of family member “B” in the desire to regain the lost family artifacts. However, I do respect that militaria collectors are some of the most generous and considerate people. I’ve seen them go out of their way to restore artifacts to the family – sometimes at their own expense. However, I advise that family members should exercise decorum and restraint while not expecting a collector to side with them and relinquish their treasured artifacts.

In early 2012, musician Phil Collins published a book detailing his passion for militaria connected to the Alamo and the people who fought and died there. Beginning early in his career, his passion for this infamous siege and battle between the Santa Ana-led Mexican army and a small, armed Republic of Texas unit (led by Lt. Col. William Travis). Collins beautifully displayed his collection across the many pages of his coffee table book, The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey. Though his publication was well-received among collectors, it did open the door for a legal challenge to the ownership of several artifacts in his possession.

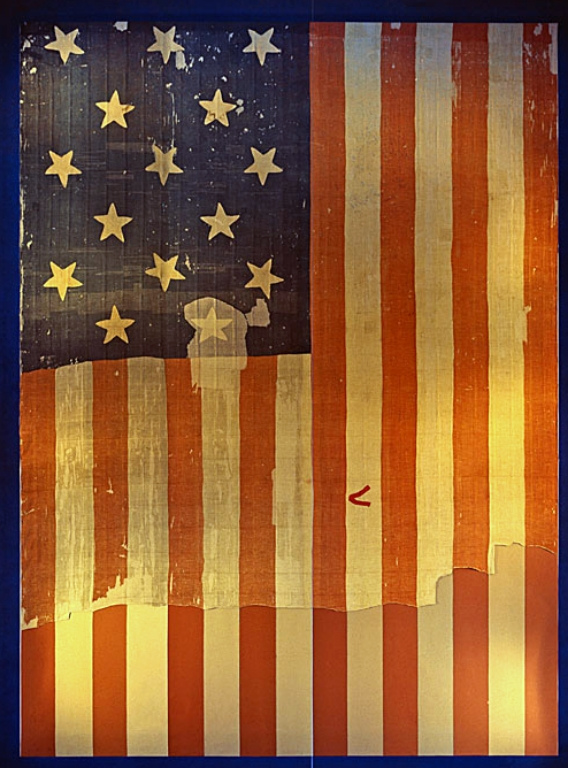

Last week, I posted an article detailing one person’s pursuit of a historic handmade U.S. flag on behalf of her former-POW father. The bedsheet-turned-national-ensign had been gifted to the U.S. Navy by the owner’s family to ensure its preservation and safekeeping to share for future generations. The veteran’s family felt strongly that the flag, while steeped with familial history and significance, the flag belonged to the citizens of the United States rather than it being relegated to “molding away in someone’s attic” or seeing it “thrown away by someone who did not know the story behind it.”

Shown as it was displayed in 1964 at the Smithsonian Institute, the Star Spangled Banner suffered deterioration and damage while in the possession of Major Armistead’s family for over 100 years (image source: Smithsonian Institution Archives).

One of the most significant military artifacts now in the possession of the People of the United States is the subject of our National Anthem. The Star Spangled Banner (the flag flown over Fort McHenry during the September 5-7, 1814 British bombardment) sat in the hands of the Major George Armistead’s (the fort’s commander) family for more than 110 years (with one public display in 1880) before it was donated by his grandson to the Smithsonian Institute.

Militaria collectors are merely caretakers and stewards of history. Though we possess these artifacts, ownership is truly not our principal focus. We expend countless resources (time and finances) preserving each piece and researching the associated veteran or historical events in order to preserve the swiftly eroding and priceless history.

Additional Related Articles: