Category Archives: World War II

Fall In! Getting Back to Militaria After a Long Summer

What a summer! For the small percentage of my readers who know me personally, understanding my absence from this blog is quite easy. For the rest of those who follow this blog, I apologize for my absence as these past few months have been consumed by some of my other passions (family time and cycling).

During my hiatus from writing about my militaria passion one would suspect that I would have increased my collection and subsequently queued up a backlog of topics and subjects to capture your attention. Sadly (for you), I’ve done neither choosing instead to spend time immersed in a myriad of activities and projects. As certain as the coming of the autumn rain (I know, it is still technically summer for a few more days), my attention can now wander back toward military history and the related objects we collect.

Speaking of working on projects, my collecting subsequent research has me steadily gathering items for a surprise shadow box for a family member. Without going into great detail, the subject of the shadow box was a Navy veteran of World War II enlisting a year (or so) prior to the Unite States’ entry. In fact, this sailor was serving aboard the USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) along with his older brother during the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) smoldering in Pearl Harbor Navy Yard dry dock #1 along with USS Cassin (DD-372) and USS Downes (DD-375) following the Japanese attack (source: U.S. Navy image).

Armed with scant few details, I embarked upon a search of available (online) sources to uncover as much data as possible in order to submit a detailed request (to obtain service records) to the National Archives (NARA). In order to create a complete shadow box (with all of the appropriate medals, ribbons, rating badge, etc.), I need to be armed with the most accurate information about the veteran’s service as I can.

One thing that I have learned through my experiences in dealing with records from NARA is that I cannot rely on the information as being entirely complete or the last, defining word in accuracy. In requesting a copy of my own “complete” service record, I noted that it lacked entire years of my service and resulted in the processor summarizing my career awards and decorations significantly short of what I actually earned. Fortunately for me, my command made an entire hard copy of my full service record upon separation from active duty. So, proceed with caution when using NARA-obtained service records and awards summaries.

An example of a WWII Navy Veteran’s shadow box (my grandfather’s) is what I am going for with this project.

For accuracy, it is best to have multiple data sources to both verify what one source states but to also discover any holes or gaps. Researching beyond individuals’ service records requires exponentially more work. If one can determine which commands (i.e. vessels) a sailor served aboard (using muster sheets), the researcher then needs to determine the specific history of that unit including campaigns and battles it participated in. This will help determine any unit awards the sailor might have earned that are not listed within the personnel file or service record.

Due to their popularity and the nature of their service, researching unit history for a well-known combatant such as a battleship or cruiser can be much more simplified than that of a fleet tug or minesweeper. For the BB-38 and this relative’s service aboard the ship, the research is quite simple and the decorations are minimal (considering the ship spent the majority of the first sixteen months under repair and modernization). During her inactive time in the shipyards, the crew was sent out to the fleet to serve where needed. Following detachment from the Pennsylvania, this relative served aboard a destroyer followed by time in confinement (for fighting), ultimately being punitively discharged late in the war.

Regardless of the manner in which his wartime service came to an abrupt end, looking back on the positives of this veteran’s wartime service and honoring it with a collection of artifacts that recognize that is a worthwhile project. This will be much appreciated by his family and serves to bring me back from my lengthy summer distraction from militaria collecting.

Following the Flag

Depicting the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment at Fort Wagner, SC, this (2004) painting, “The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground” by Rick Reeves prominently displays the flag leading the troops in battle.

Today is Flag Day. On June 14, 1777, Congress passed a resolution to adopt the stars and stripes design for our national flag. In honor of that, I felt compelled to shed some light on how the impact of the flag holds for men and women who serve this country in uniform.

Throughout the history of our nation, the Stars and Stripes have had immeasurable meaning to to those serving in uniform. On the field of battle, the Flag has been a rallying point for units as they follow it toward the enemy. From their vantage points, commanding generals are able to observe their troop movements and progress throughout battles by following the flag.

Troop reverence for the national ensign was no more apparent during the battle during the early American conflicts (Revolutionary War through the Civil War). Carrying the flag in battle was a considerable honor and the bearer was especially vulnerable to enemy fire. If the color bearer was wounded or killed, the colors would be dropped increasing the potential to demoralize the troops. If the bearer was incapacitated, another soldier would drop his weapon and pick up the flag, continuing to lead the unit toward the enemy.

In the 1989 TriStar film Glory (starring Matthew Broderick and Denzel Washington), Private Trip (Washington’s character) prevented the colors from hitting the ground when the flag bearer was shot during the assault on Fort Wagner. At that moment, the troops were mired in the hail of Confederate gun and cannon fire and the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment casualties were piling up. The troops, seeing the flag raised even higher, rose to the occasion and broke through walls of the fort.

Though Glory was a fictitious portrayal of actual events, a similar factual event took place in the November 25, 1863 Battle of Missionary Ridge in Tennessee. A young Union officer, 1st Lt. Arthur MacArthur (father of future General Douglas MacArthur) took up the regimental colors, taking it to the crest of Missionary Ridge and planting it for his regiment to see, shouting, “On Wisconsin” rallying the (24th Wisconsin Infantry) regiment. MacArthur, the last in a succession of color bearers (each falling during the assault on the ridge), was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action.

USS Grenadier crew member Engineman 1/c James Landrum holds the handmade American flag above a crowd of jubilant Omori Camp prisoners who were being liberated. August, 1945 (source: U.S. Navy photo).

Aside from their use on the battlefield, the Stars and Stripes has been known to rally servicemen and women to survive horrific and trying situations and conditions. In the numerous prisoner of war (POW) camps in Japanese-occupied territories and home-islands, American POWs were not permitted to possess a flag. When the Japanese military was on the verge of capitulation, the Americans gathered what materials they could to construct a flag which was captured in a famous image (snapped by an unknown photographer on August 29, 1945) of jubilant POWs celebrating their impending liberation.

Though I have seen the image countless times in my life, I never stopped to consider who the men were or what became of the flag. In my own collection, I have managed to maintain a few flag items of significant meaning (at least to me and my shipmates) from the first ship that I served aboard and until recently, I didn’t give them or any other flags a lot of thought. Instead my flags sat in boxes, tucked away for safekeeping. For the Omori POWs, the flag has a meaning that is tenfold more significant than the manufactured, government-issue items I possess.

My interest in this Omori POW flag was ignited when the daughter of WWI veteran Electrician’s Mate 3/c Charles Johnson, initiated a thread (on a militaria discussion board) in 2012 with a post detailing her pursuit of a hand-made flag that was made famous in a photograph of the liberation of an Allied POW camp in Japan. Her father was a survivor of the U.S. submarine, USS Grenadier (SS-210) and a POW at the Omori prison camp near Yokohama.

The daughter continued her post, “My father wondered what happened to the flag and was afraid it was molding away in someone’s attic (or) gotten thrown away by someone who did not know the story behind it.” She continued, “I promised him before he passed that I would continue to look for it.”

Over the course of the ensuing weeks, many helpful replies were submitted by forum members yet no certain leads on the flag were submitted. At the end of September a break in the daughter’s pursuit came when a gentleman submitted a post stating that he was the son of the man holding the flag (Engineman 1/c James D. “Slim” Landrum – USS Grenadier) when the photo of the POWs was taken.

The son of Landrum recalled his father’s story of how he attached the handmade flag to a fireman’s pike pole because he wanted the American flag to extend up higher above the others (displayed by the British and Dutch POWs). Afterward, the senior Landrum returned the flag to the fellow POW who supplied the bed sheet.

Armed with this information, the daughter of Petty Officer Johnson was able to locate a 1973 news article that told of the flag’s history and disposition. The Aomori camp flag was made by (then) Boatswain’s Mate 1/c Raymond Jakubielski (survivor of the USS Tanager – AM-5) and a handful of fellow POWs. In 1971, Jakubielski told the story, “In August when we heard from the camp grapevine that the Japs were about to surrender, I figured we ought to have a flag to welcome our boys in. Being the camp tailor, it was easy to get hold of an extra bed sheet and steal a couple colored pencils. Four of the mates helped color the flag and we had it up on the roof August 15, the day the Japs (sic) offered to surrender. Later, when the boats came to rescue us, our boys ran the flag up on a pole.” Having attained the rank of lieutenant prior to retiring from the navy, Raymond Jakubielski further remarked, “It was a welcome sight after seeing that rising sun thing around all the time.”

The Jakubielski family presented the flag to the U.S. Navy at Submarine Base in Norwich, Connecticut (Sunday, July 8, 1973) to Admiral Paul J. Early (a noteworthy veteran of the USS Nautilus’ submerged polar ice explorations known as Operation Sunshine) to be preserved for posterity. Subsequent to the gifting of the flag to the U.S. Navy, then-Connecticut senator Abraham A. Ribicoff arranged to have the flag flown over the U.S. Capital in tribute.

Though the information helped to close the loop for Charles Johnson’s daughter, the current disposition of the flag remained unknown. My curiosity had been piqued and I was subsequently prompted to reach out to the folks at the Naval Historical and Heritage Command. I requested information regarding the current location of the flag and, if it was in their possession, I asked if it would be photographed and shared within their Flickr photography collection. Several months after contacting them, I received the greatly anticipated affirmative response from the NHHC staff. They did, indeed have the flag within their collection and they had photographed and posted the flag at my request.

Purported to be the first American flag to fly over Tokyo, this 48-star flag was made from a white bed sheet and colored with colored pencils by prisoners at Sendai Camp No 11 in Omori Japan. It was flown in August, 1945 (source: collection of Curator Branch: Naval History and Heritage Command).

The conclusion to this story (locating the Omori flag), as happy as it may be for some readers, is not always a good one for a handful of collectors. The value in having an artifact of such incredible historical significance in the hands of archivists who will strive to preserve it and share it with the nation is immeasurable. Had the flag landed into a private collection or, worse yet, befallen the fate described by Charles Johnson, the history could have been lost.

Learn more about the American POWs in Japan:

- Submariner Prisoners of World War II

- Flags of Our POW Fathers

- Omori Tokyo Base Camp #1 Roster (Raymond Jakubielski, James Landrum)

- Fukuoka POW Camp, #3-B Roster (Charles Johnson)

Related Flag-Collecting Articles:

Decoration Day: Survivors Honor Fallen Brothers-in-Arms

A U.S. Marine with 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, Regimental Combat Team 8, pays his final respects to U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Kyle R. Schneider during a memorial ceremony held at Patrol Base Hanjar, Sangin, Afghanistan July 7. Schneider was killed in action while conducting combat operations in the district on June 30, 2011(U.S. Marine Corps photo by Corporal Logan W. Pierce).

Over the past few weeks, I have taken a little time to focus on other priorities such as my primary job (I don’t write on a full-time basis), my family and my fitness (not necessarily in that order). In response to that focus, my attention had shifted away from militaria and the various aspects of collecting during that period of time. Now that we are in the latter half of May, I need to bring my thoughts back to my passion for military history as one of the most important holidays (in my opinion) draws near.

Turning on the news this morning, my interest in the weekend forecast is piqued as the meteorologist begins to discuss the cooler than normal temperatures, the risk of rainfall and how these conditions will impact camping, boating and backyard barbecue plans. The statement really struck me as my only considerations for this weekend surrounded spending time at the various cemeteries and placing flags on fallen veterans’ graves and those of my veteran ancestors and relatives. This activity is something my wife and I have been doing dating back to my time in uniform. Making alternative plans is never a consideration and now my children are so accustomed to this practice, they look forward to Memorial Day.

WWII Navy Veteran Frank Yanick honors fallen comrades by placing a wreath at a WWII memorial in 2012 (source: U.S. Navy photo )

As our culture continues to morph and shift with each passing year, the gap of time expands and the meaning and origins of Memorial Day fade from the American population’s conscience. In a time where less than half of one percent of Americans are serving in uniform, there is virtually no understanding of the personal sacrifices (that are routinely paid by those on active duty). When someone falls on the battlefield, that societal understanding of the price paid just isn’t there. I increasingly wonder how it is that we arrived at this point.

Americans’ Participation in War

- 1860 US Population (North + South): 29 million | 3.2 million served (10.35% of population)

-

WWII era (avg. 1941-45): 136.7 million | 16.1 million served (11.8 %)

- Vietnam era (avg. 1964-74) 203 million | 9 million served (4.5%)

-

Current population: 314 million | 1.4 million serving (0.46%)

With fewer Americans serving in uniform, particularly during the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, general population is disconnected from the costly nature of service. It is no wonder that our culture tends to be more self-focused as they spend Memorial Day without considering the sacrifices that afforded them the freedom to enjoy a three-day weekend.

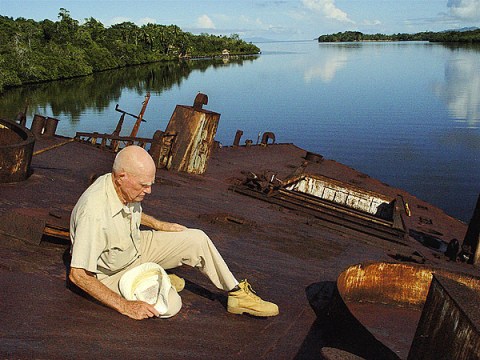

World War II Veteran Mac MacKay pauses for reflection after placing a wreath aboard his former ship, the LST 342, during a trip that several veterans made to Guadalcanal and Tulagi in 2009 (Photo courtesy of Anderson Giles).

Through my quest to understand the origins of this particular holiday, I have been led to be more forgiving of people who choose outdoor activities over trips to cemeteries. Considering that the present-day Memorial Day federal recognition was born from Decoration Day – a tradition started following the end of the American Civil War as surviving veterans began to deal with the battlefield losses of their comrades. Over the passing years, these veterans formed various veterans organizations (ranging from unit-specific to the enormous such as the GAR and UCV) and took the lead on preserving the legacy of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. Because of the efforts of these groups, battlefield and cemetery preservation and monument construction efforts were undertaken along with ceremonial gatherings for commemorative dedications.

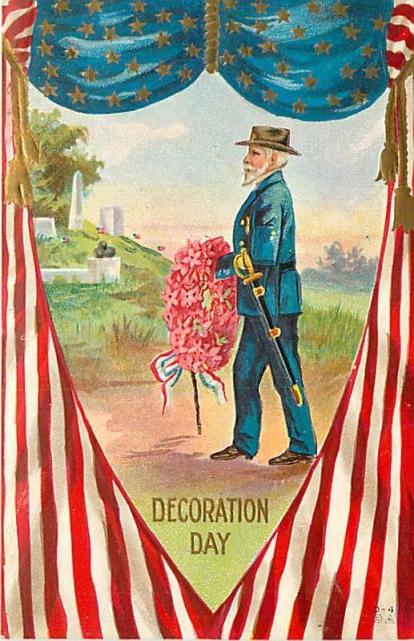

Decked in his cavalry uniform, this old veteran places a wreath among the graves of veterans on Decoration Day.

Throughout our nation’s history, it has been the veterans who have taken the lead on honoring the war dead. Mourning the loss of a brother (or sister) who fell on the field of battle is something a surviving veteran never forgets. That moment isn’t simply a memory etched into their minds but rather akin to a remaining scar in place of a missing limb. It cannot be forgotten or, as some civilians would suggest, something to “get over.”

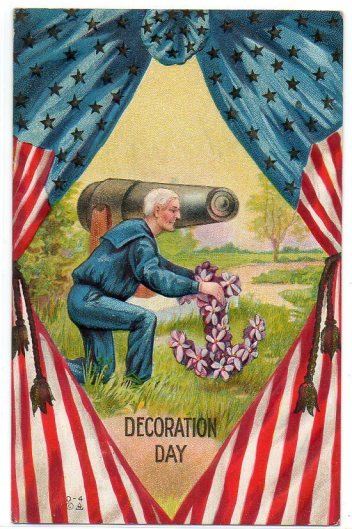

In this postcard, an old Navy veteran donned his uniform before carrying his anchor-shaped flower arrangement to the monument to render honors to the dead of the Civil War.

A few years ago, I started taking notice of various references to Decoration Day and antique items that make mention of it. One of those items that caught my attention was a postcard (from the early 20th Century) depicting an elderly Civil War veteran placing a wreath of flowers at a grave. The image, an illustration, was so moving that I was overwhelmed with emotions. The postcard evoked more recent memories of World War II veterans (at D-Day celebrations) paying respects to their fallen comrades some 70 years hence and the fresh, vivid memories painted across their faces.

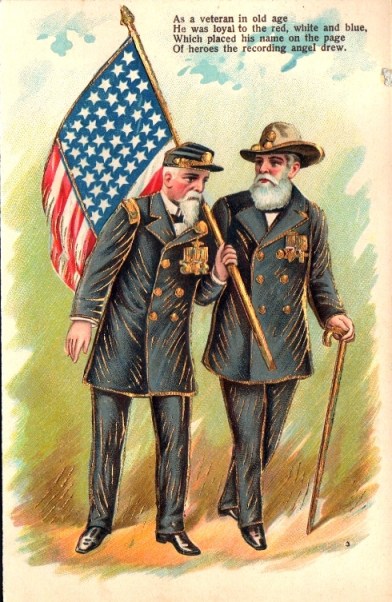

This Decoration Day postcard depicts two elderly veterans of the Civil War assisting each other as they honor their comrades who fell in battle.

Over the course of the past century, it seems that nothing has changed. Veterans still ache for their lost buddies and they are compelled to continue to honor them as long as they are physically able to do so. As a veteran, I am committed to continuing the tradition of honoring and remembering those who gave their last full measure protecting and ensuring freedom for future generations.