Category Archives: General Militaria Collecting

“Skimming” Your Way to Overpaying for Militaria

After spending more than two decades working in some capacity in a career field in the Internet industry, I have gained a considerable amount of understanding of user behaviors and tendencies. One of the most challenging user behaviors (for online content providers) to overcome is how to motivate them to actually read written content.

Countless usability studies conducted over the last decade (see UXMyths.com’s article: Myth #1: People read on the web) reveal that internet users seldom read text on the computer, tablet or smart phone screen. News media and some shady business tend to rely on this fact spending more effort on hooking audiences with headlines or product names (and photos) with the idea that the facts and details will be left unread.

Another facet of audiences not reading text is the unintended consequences. I bet this has happened to most, if not all of my readers. You search Google for an item that you want or need and hundreds of results are displayed. You see scroll through the countless listings, skimming through each blurb (abbreviated description) until you find the one that interests you the most. In a matter of seconds, confirming that the item meets your approval, credit card in hand, you quickly walk through the buying process and click the “purchase” button. After several days of tracking the shipment, it finally arrives. Excited, you tear into the box, rifle through the packaging to get hold of your eagerly anticipated item. Within a few milliseconds you discover that a mistake has been made and frustration begins to build. After a 20-minute search through your 85 gigabytes of emails, you find the order confirmation and you are ready to contact the company to confront them on their mistake. Then you realize that you are the one who didn’t read the entire product description. Sound familiar?

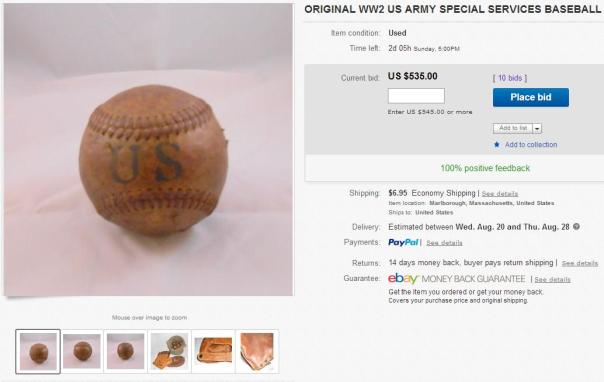

Clearly, a nothing-special WWII Special Services baseball. This is the main image used for the auction.

In the last few days as I was looking through my eBay searches, I noticed a listing for a U.S. Special Services WWII-era baseball. The listing seemed to be fairly straight forward and the $22.00 opening bid amount was consistent with what these balls routinely sell for ($20-$40), dependent upon whether they are Army, Navy or USMC variations. When I clicked on the link to view the entire auction, I noticed that the seller had included some contextual images of the ball along with other items that were not part of the auction.

No other notable markings can be seen on the baseball. This is a common WWII U.S. military baseball.

The description, in part reads:

This auction is for one (1) baseball, the gloves are shown for reference only. These balls where found in an old canvas US Army bucket that was 1944 dated along with the gloves shown. One glove is dated 1945 and stamped US Army, and the other glove is stamped special services US Army. The special services where greatly different in WW2 than they are today, back then they where in charge of recreation, and other “special items” for the troops. You will receive the ball pictured alone in the pics.

With two days remaining on this auction, the astronomically high bid is going to be a tough pill to swallow for the “winner.” The seller is probably seeing dollar signs as he imagines $500+ for each ball that he lists.

I clicked through the series of photos that showed the canvas bucket filled with baseballs and three WWII-era baseball gloves. Then, I looked at the current bid amount and my jaw hit the floor. With four days left for the auction, the current bid (of five bids from four bidders) was $275.00! How could the bids be so exorbitant; so high for a single, common WWII baseball? I re-read the description and paid close attention to the images of the ball. There was absolutely nothing that out of the ordinary about this ball. Then, it occurred to me that the bidders failed to read the full text of the auction or the auction title. When the auction closes and the highest bidder pays for the auction, he will eagerly anticipate the arrival of the ball, the canvas bucket, three vintage gloves and several other baseballs. When the diminutive package arrives, the reality will set in along with a massive pile of anger and frustration. The auction winner will either blast the seller for deception or feel like a complete idiot for not reading the auction description.

With two days left (at the time of writing this article), there are five bidders that have placed 10 bids. The current highest bid is $535.00 for an ordinary (lone) WWII baseball that is now, $490.00 overvalued.

A costly lesson is about to be learned.

Price, Provenance, Preservation and Procrastination

I have been doing some thinking lately about history and items that are specifically linked to notable events or people. One visit to just about any museum will yield an item that is connected in some form or fashion to history. The museum visitor can study the item, read the placard and then view the piece again, visualizing the associative connection. Without the placard, the item is relegated to a mere visual enhancement within the display.

Personal narratives connected to objects have considerable meaning to the person in possession of the object. For a family member to whom the item was handed down, because of the value they place upon their family member’s service, the item possesses immeasurable financial worth. If that person decides to sell the item, the story and the family history drives up their asking price well-beyond the actual value a collector is willing to pay.

As someone who inherited a decent amount of militaria from my family members, I have pondered the historical aspects of the pieces that are now part of my collection. For much of these pieces, if they stand alone, they are nothing more than objects from history. When combined with the narrative and the connection to my respective relative, they have meaning. The challenge lies in establishing (and maintaining) the historical connection.

In collecting militaria, the adage, “buy the item, not the story” should be adhered to with prejudice. Regardless of the narrative being shared by the item’s present owner, without iron-clad documented proof, an item can only be valued on it’s individual properties (demand, scarcity, condition, etc.). For those who are new to militaria (or any other vintage collectibles), the term normally applied (regarding veracity of an item’s history) is provenance (not providence):

1: origin, source

2: the history of ownership of a valued object or work of art or literature

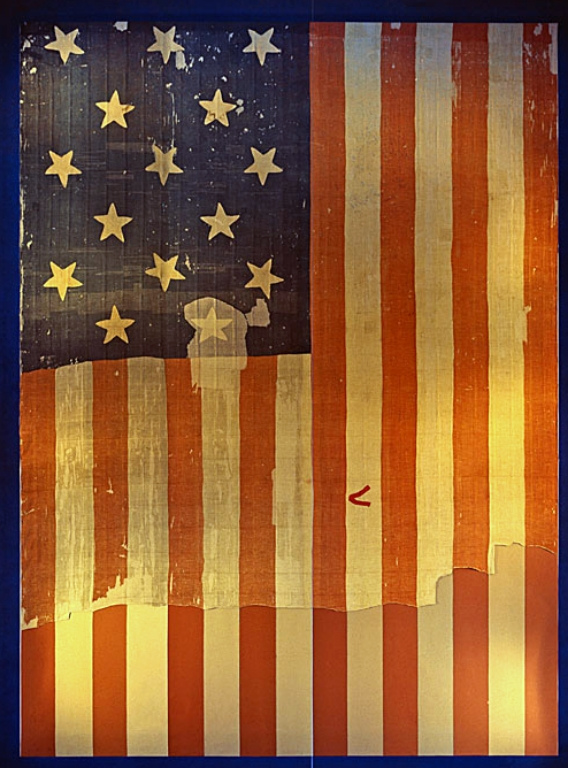

U.S. naval ensign flown over a warship during a combat deployment in the Persian Gulf during the late 1980s. The tattered ends of the fly are due to wind damage sustained during round-the-clock exposure to the elements.

One item in my collection (shown above), a flag that was flown aboard a warship during a combat engagement, possesses no identifying marks that would be able to associate it with the ship nor the engagement. However, when I acquired the item, I corresponded with the seller and saved his account of how he obtained the piece. That correspondence combined with the standard military supply markings (NSN, etc.) stamped onto the flag’s hoist and the fact that I personally know the seller (an officer who served aboard the ship) and I was present when the flag was flown, provide me with assurance that the flag and its history are genuine.

Sadly, much of the narrative history that is associated with militaria is not documented. Veterans do not take the time to preserve the history by capturing how or why the item was important enough to hold onto for the decades that followed their military service. After the veteran passes away, their estate is inventoried and these military items are disposed by the surviving family members as the history faded to oblivion.

My uncle saved this spent small arms projectile in his personal effects along with ribbons, medals and collar devices. What he didn’t save was the history of the item or the reason for keeping it for so many years.

One of the most fascinating pieces that I inherited from one of my relatives was a small arms round that had clearly been fired as evident by the striations surrounding the projectile’s body and the mushed tip. My uncle saved this bullet among his ribbons, medals, collar devices and marksmanship awards since his separation from the Army in 1954. Since I received the box containing these objects a few years after he passed, the history surrounding the bullet was lost to time. He was awarded a Purple Heart medal during WWII but the details surrounding his wound were not in his record (his records were recreated by NARA – the originals were lost in the 1973 fire), so one assumption could be a connection to his combat wound.

The desired reader-response that I have for this article is many-fold. I hope that:

-

Veterans take the time to document the history surrounding each item in their collection.

-

Collectors, dealers, and family members preserve history of the items they acquire from veterans

-

Prospective buyers press militaria sellers for solid provenance when they ask premium prices for items (being sold with a story).

Fall In! Getting Back to Militaria After a Long Summer

What a summer! For the small percentage of my readers who know me personally, understanding my absence from this blog is quite easy. For the rest of those who follow this blog, I apologize for my absence as these past few months have been consumed by some of my other passions (family time and cycling).

During my hiatus from writing about my militaria passion one would suspect that I would have increased my collection and subsequently queued up a backlog of topics and subjects to capture your attention. Sadly (for you), I’ve done neither choosing instead to spend time immersed in a myriad of activities and projects. As certain as the coming of the autumn rain (I know, it is still technically summer for a few more days), my attention can now wander back toward military history and the related objects we collect.

Speaking of working on projects, my collecting subsequent research has me steadily gathering items for a surprise shadow box for a family member. Without going into great detail, the subject of the shadow box was a Navy veteran of World War II enlisting a year (or so) prior to the Unite States’ entry. In fact, this sailor was serving aboard the USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) along with his older brother during the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) smoldering in Pearl Harbor Navy Yard dry dock #1 along with USS Cassin (DD-372) and USS Downes (DD-375) following the Japanese attack (source: U.S. Navy image).

Armed with scant few details, I embarked upon a search of available (online) sources to uncover as much data as possible in order to submit a detailed request (to obtain service records) to the National Archives (NARA). In order to create a complete shadow box (with all of the appropriate medals, ribbons, rating badge, etc.), I need to be armed with the most accurate information about the veteran’s service as I can.

One thing that I have learned through my experiences in dealing with records from NARA is that I cannot rely on the information as being entirely complete or the last, defining word in accuracy. In requesting a copy of my own “complete” service record, I noted that it lacked entire years of my service and resulted in the processor summarizing my career awards and decorations significantly short of what I actually earned. Fortunately for me, my command made an entire hard copy of my full service record upon separation from active duty. So, proceed with caution when using NARA-obtained service records and awards summaries.

An example of a WWII Navy Veteran’s shadow box (my grandfather’s) is what I am going for with this project.

For accuracy, it is best to have multiple data sources to both verify what one source states but to also discover any holes or gaps. Researching beyond individuals’ service records requires exponentially more work. If one can determine which commands (i.e. vessels) a sailor served aboard (using muster sheets), the researcher then needs to determine the specific history of that unit including campaigns and battles it participated in. This will help determine any unit awards the sailor might have earned that are not listed within the personnel file or service record.

Due to their popularity and the nature of their service, researching unit history for a well-known combatant such as a battleship or cruiser can be much more simplified than that of a fleet tug or minesweeper. For the BB-38 and this relative’s service aboard the ship, the research is quite simple and the decorations are minimal (considering the ship spent the majority of the first sixteen months under repair and modernization). During her inactive time in the shipyards, the crew was sent out to the fleet to serve where needed. Following detachment from the Pennsylvania, this relative served aboard a destroyer followed by time in confinement (for fighting), ultimately being punitively discharged late in the war.

Regardless of the manner in which his wartime service came to an abrupt end, looking back on the positives of this veteran’s wartime service and honoring it with a collection of artifacts that recognize that is a worthwhile project. This will be much appreciated by his family and serves to bring me back from my lengthy summer distraction from militaria collecting.

To Whom do Artifacts Truly Belong?

This cigarette box is engraved with the names of four WWII naval aviators (engraved” Best Wishes to The Torpedo Captain”). Though this piece is in my collection, as a collector, I am merely a steward of the history associated with it.

Historians, museum curators, historians and collectors all have differing, yet valid answers to the question of historical artifact ownership. Aside from the debate as to where an artifact belongs, there can be difficulties for collectors surrounding rightful ownership that can have more nefarious roots and beginnings.

While watching an episode of the popular PBS television program History Detectives, a woman desired to learn more about a boxed set of named (inscribed) mid-19th century Derringer pistols (season 10, “Civil War Derringers, KKK Records & Motown’s Bottom Line”) that her father purchased in the 1970s. The woman had previously had the Derringer set appraised on another PBS show, Antiques Roadshow (Pittsburgh #1607) for $30,000 but she had no idea who the original owner was or any details surrounding the history of the pistols. Included with the pistol was a document detailing the post Civil War pardon of a Confederate soldier – the name matched the one inscribed on the pistols.

The “detective,” Wes Cowan embarked on a quest to learn about the original owner (John P. Thompson) and if he was, in fact, a Civil War veteran and to learn his history if at all possible. The trail that Cowan followed ultimately led to the great, great-granddaughter of John C. Thompson who told the story of her ancestor and how the pistols were stolen from the ancestral home in the 1970s. To whom do these pistols belong?

My entrance into militaria collecting began more as a matter of happenstance rather than an active pursuit. Having a passion for local area history and genealogy began for me at an early age. As a child, I would often imagine myself digging up arrowheads or other historical artifacts while digging in the backyard or the adjacent vacant lot. Sparked by my grandfather’s stories of the “Indian Uprising” in present-day Pierce County (the father of his childhood friend told him stories of their family evacuating to the safety of Fort Steilacoom), I would picture myself finding my own piece of history.

I never pursued any real archaeological adventures as my focus shifted toward sports and other adolescent activities. After completing my schooling, I was thrust back into history but this time with a military focus when I was assigned to my first ship (following boot camp and my specialty school). I was immersed into the legacy that led to the naming of my (then) soon-to-be commissioned U.S. Navy cruiser. I began to dialog with the veterans of my ship’s namesake predecessors from WWII. From that point on, my interest in military history was truly piqued.

This sampling of Third Reich militaria items were passed down to me from my uncle (who served in the U.S. Army MIS/CIC). He sent these peices home from Germany in 1945 having liberated them following the collapse of the Wehrmacht.

Collecting, for me, began when I was asked to bring my interests and research skills to bear on some artifacts belonging to my uncle that had been stored for 50 years in my grandparents’ attic. The items were in a few trunks that were unopened since they were packed by my uncle and shipped from Germany in May of 1945. I knew very little about Nazi militaria but was up to the challenge to ascertain value and locate a buyer (my grandparents needed money to help cover their costs of care) for the artifacts. I spent a few months learning about the various uniforms, flags, headgear and badges. Little did I know that I was being immersed into the world of the high-dollar Third Reich collecting (yes, I sold most of the pieces).

My uncle served in three wars (WWI, WWII and the Korean War) rising from private to captain. This uniform and bag are from his service with Battery F the 63rd of 36th Coast Artillery Corps.

A few years later when I received my maternal grandfather’s uniforms, records, medals, ribbons, etc., I began to understand that while these items are in my possession, they really do not belong to me. I am merely safeguarding and preserving them for posterity. This has become more evident during my search for anything relating to my ancestors who served in previous centuries. I often wonder what became of their militaria. In watching the History detectives episode, my concern for lost family history is decidedly more acute as I have yet to locate a single photo (of my lengthiest pursuit – my 3x great-grandfather who served in the Civil War).

Recreating History: Researching and Assembling an Ancestor’s Civil War Artifacts:

In actively pursuing items now in my collection, I have acquired a handful of pieces that have names inscribed or engraved of their original owners. The thought has occurred to me that the potential exists for a descendant to claim rights to anything that bears a name.

People fall on hard times or may not possess interest in the military history of their ancestry. A financial need or the desire to free up storage space can drive people to divest themselves of military “junk” without pausing to realize their own connection to that history. In some cases, the heir of militaria may pass away severing ties to the historical narrative thereby devaluing it entirely.

While one person (family member “A”) could have inherited an ancestor’s militaria and subsequently opted to sell, another relative (family member “B”) might have not have been provided the opportunity to retain the history within the family. I have seen stories of this scenario playing out where family member “B” notices a post by a collector (in an online militaria forum) about something recently acquired. “B” feels the need to reach out to the collector to restore the item back to the family, often times to the point of accusing the collector of being a party to theft.

I can identify with the plight of family member “B” in the desire to regain the lost family artifacts. However, I do respect that militaria collectors are some of the most generous and considerate people. I’ve seen them go out of their way to restore artifacts to the family – sometimes at their own expense. However, I advise that family members should exercise decorum and restraint while not expecting a collector to side with them and relinquish their treasured artifacts.

In early 2012, musician Phil Collins published a book detailing his passion for militaria connected to the Alamo and the people who fought and died there. Beginning early in his career, his passion for this infamous siege and battle between the Santa Ana-led Mexican army and a small, armed Republic of Texas unit (led by Lt. Col. William Travis). Collins beautifully displayed his collection across the many pages of his coffee table book, The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey. Though his publication was well-received among collectors, it did open the door for a legal challenge to the ownership of several artifacts in his possession.

Last week, I posted an article detailing one person’s pursuit of a historic handmade U.S. flag on behalf of her former-POW father. The bedsheet-turned-national-ensign had been gifted to the U.S. Navy by the owner’s family to ensure its preservation and safekeeping to share for future generations. The veteran’s family felt strongly that the flag, while steeped with familial history and significance, the flag belonged to the citizens of the United States rather than it being relegated to “molding away in someone’s attic” or seeing it “thrown away by someone who did not know the story behind it.”

Shown as it was displayed in 1964 at the Smithsonian Institute, the Star Spangled Banner suffered deterioration and damage while in the possession of Major Armistead’s family for over 100 years (image source: Smithsonian Institution Archives).

One of the most significant military artifacts now in the possession of the People of the United States is the subject of our National Anthem. The Star Spangled Banner (the flag flown over Fort McHenry during the September 5-7, 1814 British bombardment) sat in the hands of the Major George Armistead’s (the fort’s commander) family for more than 110 years (with one public display in 1880) before it was donated by his grandson to the Smithsonian Institute.

Militaria collectors are merely caretakers and stewards of history. Though we possess these artifacts, ownership is truly not our principal focus. We expend countless resources (time and finances) preserving each piece and researching the associated veteran or historical events in order to preserve the swiftly eroding and priceless history.

Additional Related Articles: