Category Archives: General Militaria Collecting

The Spoils of War – To Whom Do They Belong?

“To the victor go the spoils.” While this quote by (then) New York Senator William L. Marcy was said regarding politics, it has been applied with regularity in reference to the taking of war prizes by the victor at the expense of the vanquished.

The taking of war prizes has been in play since the beginning of warfare and will probably continue into the unforeseeable future. The victorious, ranging from individual soldiers to military units and on up to the entire nation, maintain these treasures as symbolic of the price that was paid on the field of battle. Individuals maintain items as mementos of personal experiences and reminders of their own sacrifices. Some are painful reminders of comrades who died next to them in the trenches or aboard ship.

Mrs. Carol Conover, a NASIC employee, donated this flag to the NASIC history office years ago. It belonged to her father-in-law who brought it home from the Pacific after WWII. It is now back in the hands of Eihachi Yamaguchi’s family, the original owners.

In recent years, as aging American World War II veterans began to draw closer to their own mortality, thoughts of healing wounds that have remained open since returning home have begun to emerge. Many veterans like Clair Weeks began to see the personal items removed from dead enemy soldiers as having little personal value to them. Seeking to provide the dead enemy soldier’s surviving family members with the captured hinomaru yosegaki or “good luck” flag, Weeks began a quest to connect the item with relatives in Japan.

American museums have also taken steps to repatriate items. In Deltona, Florida, Deltona Veterans Memorial Museum staff are actively pursuing the return of a Japanese sailor’s possessions that were taken from his body by a U.S. Air Force pilot in Iwo Jima. These pieces include a silk, olive green ditty bag that held the sailor’s personal effects, a bamboo-and-paper folding fan, a Japanese flag and a collection of photographs.

Now on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, the blood-stained and bullet hole riddled ensign from the defeated USS Chesapeake (source: National Maritime Museum).

Constructed with timbers from the dismantled USS/HMS Chesapeake, the Chesapeake Mill still stands in Hampshire, England (source: Richard Thomas).

During the War of 1812 in a naval engagement between the USS Chesapeake and the HMS Shannon, the American frigate was overpowered (with 40-7 of the Americans killed in the battle) and captured by the British sailors. Taken as a prize, the Chesapeake was repaired and commissioned as the HMS Chesapeake. Upon her 1819 retirement from the Royal Navy, she was broken up with some of her timbers used to construct the Chesapeake Mill in Hampshire, England. In 1908, the blood-stained and bullet hole riddled naval ensign was sold at auction to Viscount William Waldorf Astor who, in turn, donated it to the National Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Today, the war prize flag is on public display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

Perhaps a having good, long-standing relationship with the United Kingdom contributed to the positive gesture of the 1996 repatriation of a piece of the Chesapeake’s timber to the United States. Americans can view the wood fragment at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum today.

These stories of war prizes being returned to their nations of origin are uplifting, if not inspiring. But there is another, less “sunny” war prize repatriation story afoot that has the stirred a significant amount of public outcry and resistance from U.S. veterans and military leadership.

Most Americans know very little about the conflict in the Philippines that immediately followed the end of the Spanish-American War in which the Americans received the island nation from the defeated Spanish for the sum of $20m. A small faction of Philippine nationals rose up in resistance to what was perceived as another imperialist ruling foreign nation. Seeking their independence, an uprising led by Emilio Aguinaldo lasted for three years from 1899-1902, yet some attacks on Americans continued for years.

The American survivors of the attack pose with one of the captured church bells used by Filipino insurgents to coordinate the attack against the Americans.

In a coordinated guerrilla attack upon soldiers of the U.S. 9th Infantry stationed in Balangiga (in Eastern Samar), 54 American soldiers were killed while nearly another 25 were wounded. In response to the attack, two U.S. Marine officers initiated a vicious reprisal, ordering all Filipino males 10 years of age and older bearing arms be shot. Both were subsequently courts-martialed. As part of the action against the insurgents, American soldiers captured three church bells that were used as signaling devices for coordinating the Filipino attack. The bells were shipped to the United States and have been central pieces of memorials to honor the soldiers that were brutally killed in the Filipino attack.

One of the bells from Belangigo as it appears incorporated into a monument to the fallen of the U.S. 9th Infantry (source: Military Trader).

Today, the Bells of Balangiga are the central point of controversy, in which the descendants of the insurgents who attacked the U.S. troops are seeking their return to the Philippines to be used to honor their “freedom fighters.” Many U.S. veterans see this as destroying a monument that honored the Americans who were killed and erecting a monument that instead honors their killers.

Since 1997, talks have taken place at the highest political levels between the two nations as the return of the bells could go a long way in garnering political and national relations capital for all involved should the decision be reached to repatriate the cherished bronze castings. Today, the bells remain as placed at what is now known as Francis E. Warren Air Force Base (formerly, Fort Russell).

California Congressman Demonizes Collectors with Introduction of a Bill

The Purple Heart Medal has been awarded since 1932 to veterans who were wounded or killed in action in WWI through the current conflicts. Showing the reverse of the PHM with the words, “For Military Merit” and the space beneath where it is traditionally engraved with the recipient’s name and rank.

When citizens perceive what they think to be a travesty or tragedy, they scream to their lawmaking-representatives to create laws in order to make changes that will help them to feel good that they did something positive. It is a common action among Americans to want to bring about changes, to right wrongs and to make society more safe. We feel better about ourselves when we stood up and participated in the process. Sadly, the only thing positive with many of these actions are that those scant few people can feel good while the rest of society has to deal with the negative ramifications and unintended consequences brought about by these actions.

- The Purple Heart Medal (photo source: PurpleHearts.net)

- Affectionately known as a “coffin case,” this presentation box is inscribed with the name of the medal in gold leaf.

- This is a World War II Purple Heart Medal set complete with the ribbon and lapel device in the correct presentation case.

This week new federal legislation was proposed by U.S. Representative Paul Cook (R-CA-8) to address what he and a select few Americans feel is a troubling trend – the sale of Purple Heart Medals (PHM) among collectors. HR 6234 (known as the “Private Corrado Piccoli Purple Heart Preservation Act”) if passed would “prevent merchants from profiteering from the sale of military-issued Purple Hearts, eliminating the market and making it easier to return them to their rightful owners.” Taken at face-value, this seems to be a very noble goal. Who wouldn’t want Purple Heart Medals returned to their rightful owners?

“These military collectors cheapen the Purple Heart by buying and selling this symbol of sacrifice like a pack of baseball cards,” said Cook, who served 26 years in the Marine Corps before joining Congress, rising to the rank of colonel and receiving two Purple Hearts for injuries sustained during the Vietnam War. – See: Selling Purple Hearts would be illegal if this bill becomes law

One of the underlying beliefs of the bill’s sponsor and his supporters is that militaria collectors are profit-seeking undesirables who buy and sell these vaunted medals, capitalizing on the specific aspects surrounding the awardees’ circumstances (for which the medal was given) such as:

- If the veteran was killed in action (KIA)

- If the battle in which the veteran was wounded (mortally or otherwise) was notable or pivotal

- If the veteran was note-worthy:

- a famous or semi-famous service member

- a member of a notable military unit or vessel

In viewing advertisements of PHMs for sale, these facts are often presented in the medals’ descriptions not too dissimilar to features of a used automobile, rendering them seemingly insensitive and cold. I admit that even I am put-off when I see how they are exhibited as available for purchase.

This Purple Heart Medal collector goes to great lengths in order to demonstrate to the public the terrible costs of war and the personal sacrifices made by Americans. By providing viewers with the ability to see the medals, view the veterans’ photos and read their story, this collector, like countless others, ensures that the individual American history is not lost to time. (Source: ToHonorOurFallen.com/Edward L. Maier III)

Regardless of the manner in which the medals are listed, most of the collectors that I have encountered are not only sensitive regarding the nature of these medals and the reason that they exist and are awarded, they go to great lengths to gather the facts surrounding the medals in order to emphasize the veterans’ service and the gravity of the price that is repeatedly paid by them for our nation. The steps that are taken by these collectors in order to preserve the history is extremely honoring and very sensitive towards the veteran and the surviving family members (in the case of KIAs-awarded medals).

There are many militaria collectors who also wore the uniform of this country. Many of them, like me, take pride in our service and that of others and we strive to preserve the history that is being discarded by families of veterans (and even the veterans themselves). One of my colleagues, a fellow Navy veteran, is pursuing his next book project (his most recent work, Blue Seas, Red Stars: Soviet Military Medals to U.S. Sea Service Recipients in World War II, is a similar, monumental undertaking that recognizes those American servicemen who were decorated by the Soviet Union for heroic acts in convoy and anti-submarine duty in the North Atlantic during WWII) that focuses entirely on the Purple Heart Medals that have been awarded to service men and women who were killed in combat. Many of the hundreds of medals that he has personally photographed for this book are in the hands of collectors who want to see the stories of the awardee preserved and shared in perpetuity.

Bear in mind that I make that statement as both a collector and as someone who is very sensitive about the issue of PHMs being bought and sold (due to the somber nature of why these medals are awarded, owning a medal that is connected to such significant personal loss is too painful for me to see past). Aside from the “For Sale” listings where the current owner painstakingly describes as much detail surrounding the veterans’ service and how they fell in combat, I also have difficulty when I read about an excited collector’s “find.” There is a fair amount of gray area between celebration of landing a medal that helps the collector tell a particular story (in their collection’s area of interest) and one that a collector picked for a very insignificant amount but will garner significant profit when it sells. I know that I am not the only collector who struggles when we see this on display. I also don’t mean to disparage any fellow collector for what brings them excitement and joy with their collection.

One person in particular who is celebrating the introduction of this bill and is hopeful to see it passed is Zachariah Fike (Captain, Vermont National Guard) who is the founder and CEO of Purple Hearts Reunited, a non-profit organization whose mission is to return Purple Heart Medals to the awardees or their families. “We are absolutely humbled to see Private Corrado Piccoli being honored through this bill by Congressman Cook,” reads a Facebook post (dated October 3, 2016) by Fike’s organization. Fike has historically been in opposition of collectors, stated to NBC News in 2012, “’It wouldn’t be fair for me to say they’re all bad. But the ones I have encountered, I would consider myself their No. 1 enemy,” Fike said. “They’re making hundreds or thousands of dollars on (each one) these medals. They think it’s cool. It’s a symbol of death. Because of that, it has a lot of market interest and it has a lot of value.”’ In my near-decade of collecting, I have learned that Fike’s assessment (of medal collectors) is the rare exception rather than the norm.

There is little doubt that Congressman Cook is responding in lockstep with Fikes (who has been vocal in his frustration with collectors’ who did not surrender their medal collection to him) and believe that in banning the sale of these medals will compel collectors to hand them over to organizations and people who are bent on returning them to families. What these well-intentioned people have overlooked is that so many families are the ones who have divested the heirlooms to begin with. For many reasons such as:

- No connection to the distant, deceased relative

- The family suffered a falling out with the veteran (broken marriage, the veteran abandoned his family, etc.) and the medal is a painful reminder

- The survivors are opposed to war, the military and anything that is connected to or associated with it

- Would rather see the medal and history preserved by a collector who has demonstrated this capability

There are many stories of medals being discovered in the most deplorable situations; some of the worst being discovered in dumpsters and curbside garbage cans. As the only one who had an interest in the military history of my family, I was bequeathed militaria from my relatives that included Purple Heart Medals (one of my uncles was wounded in action during both WWI and II). No one else cared. Now I am responsible to ensure that these items are cared for at the end of my life. If this bill passes and no one wants to inherit these items (and with the glut of nearly two million medals being in the same situation as mine), where will they end up?

What happens when Fike comes calling on the family having “recovered” a PHM from a collector only to find that doing so, causes grief with the people who wanted to rid themselves of the item(s) to begin with. What becomes of the medals then? How does this proposed law deal with the collections of PHMs when the collectors pass away and have no future collectors to transfer the medals to? According to the National Purple Heart Hall of Honor, the current estimation is that there have been more than 1,800,000 Purple Heart Medals awarded since 1932. Of those, how many thousands reside within individual militaria collections and what is to become of them? What percentage of those are unwanted by the families?

One of the unintended consequences of the previously established laws (banning the sale of the Congressional Medal of Honor [CMOH]), countless American artifacts have left our shores and landed in the hands of foreign collectors undoubtedly to ever return to our shores. The law that prevents the sale (similar to the one proposed by Congressman Cook will force collectors (who are seeking to recoup all or part of their investment) to locate buyers outside of the United States. Worse yet, some domestic CMOH collectors who have been in the possession of their medals predating the law (that prohibits the sale) have since been discovered by the federal authorities; their medals confiscated and subsequently destroyed by the FBI.

Banning the sale does very little in reaching the stated goal – to facilitate the return of the Purple Heart Medals to veterans and families. It also creates a problem for law enforcement. With 1.8 million medals in existence, how do they discover transactions, track ownership of medals and what becomes of those recovered who have no surviving family with which to receive said “missing” medal?

Despite what Captain Fike stated about collectors, his actions contradict him in regards to how he truly considers militaria and medal collectors. His push to locate a legislator to take such short-sighted and drastic steps to ban the sale of these artifacts are a direct assault of collectors that will have long-term negative impact on his non-profit organization’s noble efforts. The bill will also include penalties for veterans and families who attempt to sell these medals; there are no exclusionary provisions nor exceptions. Congressman Cook and Captain Fike appear to be targeting (whom they deem to be) the victims in the Purple Heart trade along with the collectors.

My voice hardly matters and no one would bother to take note of what I have to say in regards to this issue. Nevertheless, I believe that this good-intentioned law is ill conceived and will ultimately make it more difficult to restore the medals to the families and veterans who want to see them returned.

Related Articles:

Collecting Militaria: Historical Preservation or War Glorification?

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.”*

I started this blog as a continuation of a similar effort that I undertook (as a paid gig) for a large cable television network. I spent some time contemplating a suitable name for this undertaking, settling on The Veteran’s Collection for a number or reasons. The simplest of those reasons was to express my interest in militaria and how my status as a veteran guide both my interests and desire to preserve history.

Though my wife might argue, my collection of patches is rather small as compared to those of true military patch collectors. I tend to be more specific about the patches I seek (such as this USS Tacoma crest edition).

Often, I equate my collecting of military items in the vein of being a curator of military history and the role that the military has played in the securing and preserving of basic freedom for our nation (and for the people of other nations who have been trying to survive under repressive regimes). In gathering and collecting these items, it may appear to some that I am glorifying war. Having in my possession weapons (firearms, edged weapons, munitions, etc.) might signify glorification to the untrained eye however these items are part of the overall story being conveyed by collection.

As I scour my collection, I begin to realize that the overwhelming majority of items are Navy-centric. This 1950s U.S, Army cap is part of the display that I am assembling of my paternal grandfather’s older brother’s service.

I am a fairly soft-spoken person when I am out in public (though people who truly know me would have a difficult time believing this). When political conversations emerge near me (when waiting in line or casually walking past strangers in public settings) I have heard, on many occasions, discussions focus on perceptions of men and women who serve ( low-key or have served) in the armed forces. Often times, gross mis-characterizations regarding people in uniform begin to emerge as the dialog devolves into denigration of active duty and veterans as being war-hungry criminals, bent on killing innocents (women and children). I can’t count how many times I have stood in line, listening to people in front of me expressing how frustrated they are when they see a soldier in uniform ahead of them receiving a discount for a food item or service equating their time in service as legalized murder.

I served ten years on active duty and had two deployments into a combat theater, one of which I and my comrades were engaged by the enemy. In all of those ten years, I cannot recall a single person whom I served with who desired or wished to see combat. We prepared and trained for it hoping to never see it. I don’t think that I have ever met a combat veteran who wanted to talk openly about their time under fire. To have the uneducated civilian boil down our willingness to don the uniform, train for years while understanding fully that at some point during our service, we could see the horrors of combat as being blood-thirsty war-mongers only serves to show the extent of their ignorance.

I recently read two articles today concerning veterans of World War II who have (or had) committed their remaining years educating people about the horrors of war that each of them faced.

The first article was about one man, an IJN fighter ace Kaname Harada, who took every moment that he had left in order to do what the Japanese government is failing to do; educating younger generations to warn them about being drawn into future wars. “Nothing is as terrifying as war,” he would state to an audience as he spoke about his air battles from Pearl Harbor to Midway and Guadalcanal. As I read the article, I zeroed in on a chilling quote by one of Harada’s pupils, Takashi Katsuyama, “I am 54, and I have never heard what happened in the war.” He cited not being taught about WWII in school, continuing, “Japan needs to hear these real-life experiences now more than ever.” I am baffled that a man who is a few years older than me was not taught about The War in school.

In the second article, Army Air force fighter pilot, Captain Jerry Yellin, who like Harada, is educating young people about what he sees as futility of war. He is concerned that young Americans do not have an understanding of the realities of war nor what it is like to fight. “We’re an angry nation,” said Yellin. “We’re a divided nation: Culturally, monetarily, racially and religious-wise we’re divided.” What the veteran of 19 P-51 missions over Japan said (in another article) regarding war is often lost on those who are pacifists (at any and all costs) and lack understanding, “War is an atrocity. Evil has to be wiped out.” He continued, “There was a purity of purpose, which was to eliminate evil. We did that. All of us. So, the highlight of my life was serving my country, in time of war.”

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana

Both of these men clearly understand the cost of war and the hell that they faced when they took up arms and yet neither of them could be characterized with the ridiculous “war mongers” moniker often applied to warriors.

The reasons that people collect militaria are as diverse as each of the hobbyists’ backgrounds. The community of collectors can be completely aligned and in lock-step with each other on some militaria discussion topics and in near animus opposition on others. I tend to stay away from collecting medals and decorations; specifically, anything awarded to a veteran (or, posthumously to his family) due to how a great number of collectors commoditize certain medals (Purple Heart Medals, specifically). I withhold judgment as I abstain from even discussing the medals in question. For the laymen, a Purple Heart is awarded to service members wounded or killed in action. Collectors attach increased value for medals awarded (engraved with the recipient’s name) for posthumous medals; if the person is notable or was killed in a famous or infamous engagement, the value compounds (there are several other contributing factors that influence perceived monetary value).

- This is the Western Union telegram that was delivered to PFC Skavinsky’s wife, notifying her of his death. It took 10 days to get word to her. (Source: PurpleHearts.net)

- The Purple Heart Medal (photo source: PurpleHearts.net)

- The back of Skavinsky’s Purple Heart shows the official engraving of his name (Source: PurpleHearts.net)

- PFC Skavinsky’s accompanying certificate documenting the awarding of the medal and the date in which he was wounded. (Source: PurpleHearts.net

Purple Heart Medals are a very sensitive area of military collecting and nearly every medal was awarded to combat veterans – soldiers, marines, sailors and airmen who were serving in a war or wartime capacity. There are several collectors who use their Purple Heart collections to demonstrate the realities of the personal cost of war. These caretakers of individual history, such as this collector, painstakingly preserve as much of the information surrounding the WIA and KIA veterans, often maintaining award certificates and even the Western Union telegrams that were presented to the recipients’ parents or widows. Seeing a group with the documentation together is heart-wrenching.

A few of the selected items that my uncle brought back at the end of the war in Europe.

Militaria collecting can be very personal as many of the items, like medals (such as the Purple Heart) actually belonged to a person who served. In my collection, I have uniforms from men who served from as far back as the early 1900s up to and including the Vietnam War (not including my own as seen in this previous post) with the majority centered on World War II. Nothing could be more personal than the uniform worn by the veteran. Having personal items, in my opinion, enhances the collecting experience because of the desire to research what that service member did when they served. Uncovering a person’s story is to understand the sacrifice and cost of leaving family behind to serve rather than glorifying war itself.

Also in my collection are artifacts that were brought back by the veterans from the theater in which they served. While to some people, viewing these items may conjure negative and visceral responses, they still serve to tell a story that shouldn’t be forgotten. One of my relatives returned from German having recovered a great many pieces from the Third Reich machine after it was defeated by May of 1945. Still, this is not celebrating war nor the defeat of a (now former) foe.

There are other facets of my collection that are touch on the functions of engagement and combat; specifically armament and weapons. I have a few pieces that I inherited that, at some point, I will be delving deeper (on this blog) as they do fascinate me. I need to spend some time expanding my knowledge a bit more in order to present these pieces with a modicum of understanding (alright, I’ll admit that I don’t’ want to sound uneducated on my blog). Frankly, weapons are not my forte’ but what I own (a small gathering of edged weapons and ordinance), I have spent some time learning about them.

- I have a smattering of edged weapons (or, in this case, an edged tool) that I mostly inherited. This bolo knife was carried by Navy Pharmacists Mates (a.k.a “corpsmen”) who were attached to USMC units. The “U.S.M.C” embossed on the blade represents the United States Medical Corps.

- M1917 U.S. Military bolo knife and scabbard.

- 1942 M1 Garand Bayonet

Preserving history is paramount to helping following generations to both understand the cost of war and that, while doing what is necessary to avoid future wars, serves to illustrate that nations not only should but must take a stand against tyranny and evil.

See also:

* Military Memoirs of a Confederate, 1907, Edward Porter Alexander

Civil War Shadow Box Acquisition: “Round” One is a Win

- (Note: This is second installment of a multi-part series covering my research and collecting project for one of my ancestors who was a veteran of the American Civil War)

- Part 1 – Shadow Boxing – Determining What to Source

- Part 2 – Civil War Shadow Box Acquisition: “Round” One is a Win

- Part 3 – Due Diligence – Researching My Ancestor’s Civil War Service

- Part 4 – Boxing My Ancestor’s Civil War Service

Yesterday’s mail delivery netted for me my initial foray into American Civil War artifact collecting. I like to counsel would-be militaria collectors to focus on their collecting – choose a specific area of interest and pursue that area. While I have been trying to live and collect by this guidance, to the casual observer it would appear that, with this purchase, I have altered my stance.

My collecting focus has been centered upon one thing: creating displays or groups that provide a visual reference of specific veterans in my family and honor their service. That direction has predominantly led me to twentieth century militaria collecting as the items would pertain to those individuals’ service. Another contributing factor has been the affordability and abundance of World War II militaria. It has been a bit more challenging to assemble artifacts from the Great War.

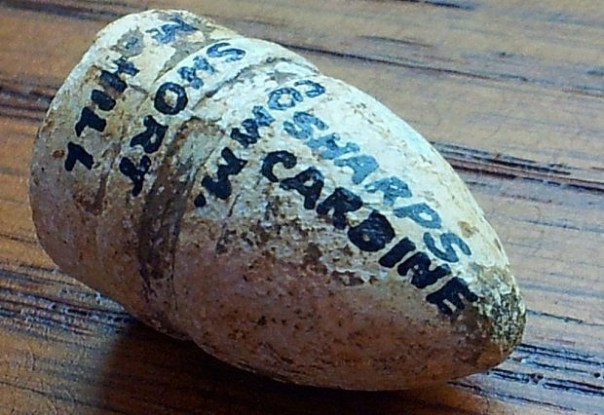

Showing the beautiful labeling on the .52 caliber Sharps Carbine round acquired for my shadow box display.

The package that was delivered to my door yesterday was small and weighed very little and yet this item would be one of the central pieces in my small display dedicated to the service of my great, great, great grandfather. In researching him and discovering certain details of his service, I decided that I wanted to assemble some significant artifacts for a shadow box that would provide subtle.

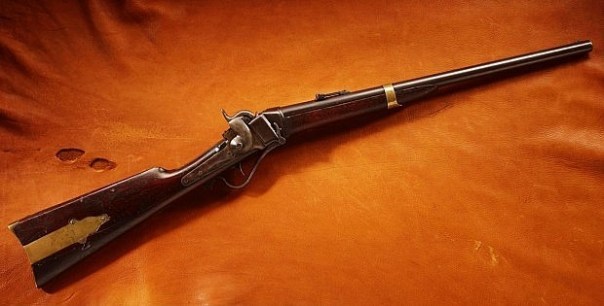

Understanding that my 3x great grandfather served in a cavalry unit, I began to research the engagements they participated in. While I am still waiting for my ancestor’s service records, I made some safe assumptions as to which specific campaigns and battles that he participated in, following his regiment and company’s history. Armed with those details, I began to search for anything that could be closely connected to him. Having researched the weaponry, I determined that he would have carried a Sharps Carbine by the time his regiment participated in the battle at Malvern Hill and used that information to search for specific artifacts.

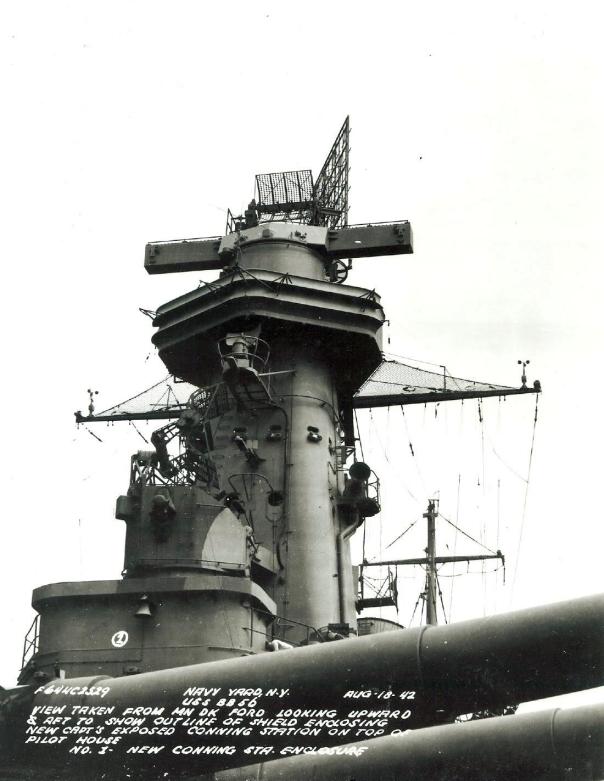

This Model 1859 Sharps “New Model” Carbine .52 Cal rifle was the principal weapon for the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry – once they shed their lances (source: National Firearms Museum).

My search led me to several choices of “dug” artifacts, many of which were in my budget. I honed in on one specific bullet round, a .52 caliber “New Model” Sharps Carbine round that had, more than likely, been dropped on the battlefield. The round is beautifully labeled with details about where it was found and what it is and it came from the collection of a known Civil War expert. Feeling safe about the item, the seller’s history and the aesthetic qualities, I went ahead with my purchase.

For the remaining items, I will continue to be patient and educate myself before I pull the trigger (pun intended).

Continued: