Author Archives: VetCollector

Cryptology and the Battle of Midway – Emergence of a New Weapon of Warfare

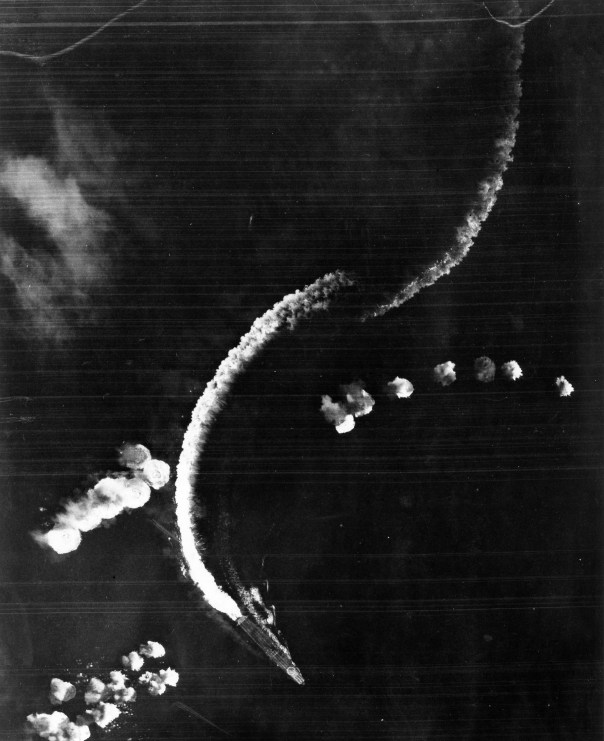

Here the Japanese carrier Hiryu dodges bombs dropped from Midway-based B-17 bombers (source: U.S. Navy).

The outcome of the war hung in the balance. Until now, the United States Navy’s operational effectiveness and readiness was in peril as they had suffered significant losses of the scant few carriers they had in the Pacific Fleet prior to December 7, 1941. The Imperial Japanese naval forces had extended their effective reach to include most of the Western and Southern Pacific and were seeking overall dominance of the ocean. The only opponent standing in their way was the severely weakened U.S. Navy.

In the previous six months, the American Navy had sustained strategic losses near Java with the sinking of the USS Houston (CA-30) in the Sunda Strait and the USS Edsall (DD-219) in the Java Sea, both on March 1.

Looking to put the Japanese on the defensive, American forces struck the Japanese homeland launching a (psychologically) successful air strike from the deck of the USS Hornet, causing Japanese military leadership to start holding back naval and aviation resources as a home guard, reducing the offensive capabilities. Japan had to consider herself vulnerable for the first time in the war while trying to convince citizens otherwise.

Continuing to press their imperial expansion Southward (Australia’s natural resources the ultimate goal), the Japanese, preparing for an offensive to take Port Moresby, New Guinea, began mobilizing the Combined Fleet in the South Pacific. American Forces countered and pressed for an attack which resulted in what came to be known as the Battle of the Coral Sea. While this battle was a strategic win for the United States, it was substantially painful losing the carrier Lexington and sustaining substantial damage to the Yorktown, leaving the Navy with just two serviceable flat tops, Enterprise and Hornet.

The Coral Sea battle demonstrated that over-the-horizon naval warfare had emerged as the new tactic of fighting on the high seas, as the carrier and carrier-based aircraft surpassed the battleship as the premier naval weapon.

While the Navy was very public in developing aviation during the 1920s, behind the scenes, a new, invisible weapon was being explored. Radio communication was in its infancy following World War I and adversarial forces were just beginning to understand the capabilities of sending instantaneous messages over long distances. Simultaneously, opponents were learning how to intercept, decipher and counter these messages giving rise to encryption and cryptology.

Officially launched in July of 1922, Office of Chief Of Naval Operations, 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section, Communications Security (or simply, OP-20-G) was formed for the mission of intercepting, decrypting and analyzing naval communications from the navies of (what would become) the Axis powers: Japan, Germany and Italy. By 1928, the Navy had formalized a training program that would provide instruction in reading Japanese Morse code communications transmitted in Kana (Japanese script) at the Navy Department building in Washington D.C. in Room 2646, located on the top floor. The nearly 150 officers and enlisted men who completed the program would come to be known as the “On The Roof Gang” (OTRG).

By 1942, Naval Cryptology was beginning to emerge as a viable tool in discerning the Japanese intentions. The Navy was beginning to leverage the intelligence gathered by the now seasoned cryptanalysts which ultimately was used to halt the Japanese Port Moresby offensive and the ensuing Coral Sea battle. However, the Japanese changed their JN-25 codes leaving the naval intelligence staff at Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (known as Station HYPO), headed by LCDR Joe Rochefort, scrambling to analyze the continuously increasing Japanese radio traffic.

A breakthrough in deciphering the communication came after analysts, having seen considerable traffic regarding objective “AF,” suggested that the Japanese were targeting the navy base at the Midway Atoll, 1,300 miles Northwest of Hawaii. While this information would eventually prove to be

invaluable and was ultimately responsible for placing Pacific Fleet assets in position to deal a crushing blow to the Japanese Navy, it was anything but an absolute, hardened fact. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz risked the balance of his carriers (Hornet, Enterprise and Yorktown) sending them to lie in wait of the assumed impending attack.

The attack came and the prepared American forces struck back, inflicting heavy damage to IJN forces, sinking four carriers, one cruiser and eliminating 250 aircraft along with experienced aviators. Though the war would be waged for another three years, the Japanese were never again on the offensive and would be continuously retracting forces toward their homeland. The tide had been turned.

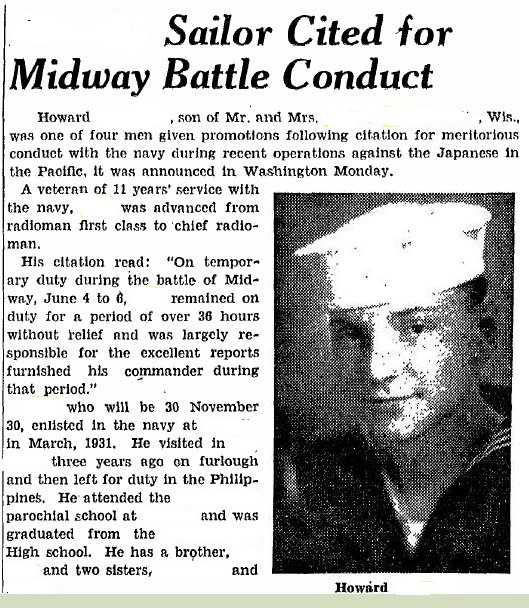

News clipping citing my uncle’s meritorious promotion (one of four sailors advanced for actions during the Midway battle) by Admiral Spruance .

On this 74th anniversary of the Battle of Midway, I wanted to spotlight a different aspect of the history of the battle, the emergence of cryptology as a strategic weapon, and share some of my own collection of that focuses on one of the original OTRG alumni, my uncle Howard.

Howard enlisted as an Apprentice Seaman in the Navy in 1932 (despite what the news clipping states) and proceed to serve in the fleet while working toward a radioman rating. He would be rated as a radioman 3/c in 1934 and accept an assignment to cryptological training at OP-20-G. In the years leading up to the war, he was assigned to Station HYPO and Station CAST (at the Cavite Navy Yard, Philippine Islands) transferring days before the Japanese raid.

- This service record entry shows that my uncle was meritoriously promoted for his actions during the Midway battle.

- This service record entry was also the text of my uncle’s commendation from Admiral Fletcher (acting CTF-16) for providing continuous intel.

Assigned to Station HYPO in early 1942, he would work closely with Commander Rochefort in code-breaking efforts and is purported (in my family circle) to have sent the transmission to Midway personnel to send un-coded messages about their inoperable evaporators, which ultimately led to the confirmation of Midway as Objective “AF.” He would be assigned to the Admiral’s staff (Admiral Raymond Spruance, who was substituting for Halsey at the time) aboard the Enterprise and would receive a meritorious promotion from the admiral as the result of his round-the-clock duties for the duration of the 4-day battle.

- Though these jackets never belonged to my uncle, they represent his achievement – reward for his dedication to duty during the most pivotal naval battle of WWII.

- Assembled from serviceable components from a few WWII navy hats, my dress blue chief radioman display is closer to being complete with this cover.

By 1944, my uncle had been promoted to the officer ranks, making Chief Radio Electrician, warrant officer-1. A career spent in naval cryptology, my uncle retired after 30 years of service.

Regretfully, none of my uncle’s uniforms, decorations or medals survives to this day. Neither of his sons inherited anything from their father’s more than 30 years of naval service. In my decision to honor him, I requested a copy of Uncle Howard’s service record (as thick as an encyclopedia) and began to piece his military tenure together by gathering uniforms and other associated elements. My collection of assembled uniform items representing his career, while not yet complete, has been a long endeavor – dare I say, a labor of love?

Commemorating and Collecting Midway

Approaching June 4, many Americans will be reminded of a pivotal event that took place on this very day during World War II, when a massive armada of ships carrying troops that were preparing for an invasion (that would commence on the morning of June 6th, 1944). The plan was to establish a foothold in enemy-held territory, extending their reach with a new base of operations. Thinking of this date in particular, Americans will conjure thoughts of paratroopers flying over a stretch of water as they begin to traverse flak bursts en route to their targets.

For the past several years, veterans and their families have made their way to the hallowed ground on the beaches and drop zones in and around Normandy, France, seeking to re-trace their steps on the ground where the D-Day Invasion commenced. Though few of those brave men remain this eve of the 72nd anniversary, the children of those veterans will be joined by grateful citizens as they remember the sacrifices made by so many men on that day in 1944. With so much attention given to Normandy (especially by Hollywood in recent years with Saving Private Ryan and the Band of Brothers series), typically overlooked (when thinking about this date) is a battle that arguably had the same or even greater impact on the War’s outcome.

The Battle of Midway took place at a time when the U.S. was still ramping up to fight, having been caught unprepared for war. American Army ground troops wouldn’t be committed for a full-scale assault until November of 1942 with Operation Torch in North Africa. The Marines wouldn’t begin any offensive campaigns until landing craft bow ramps were dropped onto the shores of Guadalcanal. This meant that the majority of the fighting that was taking place since December 7, 1941 was being carried out by U.S. naval forces.

Owning a sailor’s photos may seem odd to some, but they could be one-of-a-kind images that you otherwise might not see. This hand-painted USS Minneapolis photo album is a fine example (source: eBay image).

This group of medals from a USS Enterprise veteran largely contains modern hardware. The dog tags appear to be original to the veteran (source: eBay image).

In commemorating the 70th anniversary of the battle, regrettably little ceremonial attention will be paid to the few surviving veterans who are, at the very least, in their late 80s. Yet, we need to remind ourselves of the significance of this battle and remember those who risked it all and sent the Japanese forces into a three-year retreat.

Being a collector (primarily interested in Navy militaria), it takes a fair amount of legwork and an awful lot of providence to acquire authentic pieces that may have been used during this battle. We have to ask ourselves, “what would be the most target-rich focus area that we can pursue for treasure?” Clearly, the answer to that question would be veterans’ uniforms. Considering that there were two task forces containing 28 vessels (and 260 aircraft), there would be literally thousands of veterans each with multiple uniforms to choose from–if you can determine that they actually participated, attached to one of these units.

Those interested in obtaining pieces of ships or aircraft will have an infinitesimal chance to locate authentic items for their collection… but that means there is still a chance. Below is a list of every U.S. Navy ship that participated in the battle (I’ll leave it up to you to research the participating aviation squadrons from the carriers and Midway Island):

- Carriers

USS Enterprise, USS Hornet, USS Yorktown - Cruisers

USS Astoria, USS Minneapolis, USS New Orleans, USS Northampton, USS Pensacola, USS Portland, USS Vincennes, USS Atlanta - Destroyers

USS Aylwin, USS Anderson, USS Balch, USS Benham, USS Blue, USS Clark, USS Conyngham, USS Dewey, USS Ellet, USS Gwin| Hammann, USS Hughes, USS Maury, USS Monaghan, USS Monssen, USS Morris, USS Phelps, USS Russell, USS Ralph Talbot, USS Worden - Submarines

USS Cachalot, USS Cuttlefish, USS Dolphin, USS Finback, USS Flying Fish, USS Gato, USS Grayling, USS Grenadier, USS Grouper, USS Growler, USS Gudgeon, USS Narwhal, USS Nautilus, USS Pike, USS Plunger, USS Tambor, USS Tarpon, USS Trigger, USS Trout - Oilers

USS Cimarron, USS Guadalupe, USS Platte

- This Battle of Midway Commemorative Pillow appears to have been produced during WWII (source: eBay image).

- Showing the nice silkscreen details of the Midway Commemorative pillow (source: eBay image).

Remember, you can also seek commemorative items, vintage newspapers or original photographs, or named (engraved) medal groups from veterans who fought in the battle – creativity and a lot of research will help you reap great reward!

Decorating Sacrifice: Honoring Our Fallen

Most Americans have no connection Memorial Day, their heritage or to the legacy left behind by those who gave their lives in service to this country.

This weekend, we Americans are being inundated with myriad auditory treats, such as the sound of burgers and hot dogs sizzling on the barbecue grill, the roar of the ski boats tearing across the lake, the rapid-clicking of fishing reels spinning, or the din of children playing in the backyard. All of this points to the commencement of summer and the excitement-filled season of outdoor activities, vacations and fun. The bonus is that we get to extend this weekend by a day and play a little harder as that’s what this weekend is all about!

With the opening volleys of artillery (the Confederates firing on Fort Sumter) in the early morning hours of Friday, April 12, 1861, a war of the bloodiest nature commenced within the confines of what was known as the United States of America, but which was anything but united. The division of the states had been years in the making as the founding fathers could hardly agree on the slavery issue when trying to establish a single Constitution that would bind the individual states together as one unified nation. The division led to an all-out conflict—a war that would pit brother against brother and father against son—that wouldn’t cease until almost exactly four years later (at Appomattox on April 10, 1865) and three-quarters of a million Americans were dead (the number was recently revised, up from 618,000, by demographic historians).

In the days, weeks, months and years that followed, the sting of the Civil War would linger as families suffered the loss of generations of men. The Southern States where battles took place had cities that were obliterated. The agricultural Industry was devastated. The business operation surrounding the king crop of the south, cotton, heavily dependent upon slave labor, had to be completely revamped. Many plantations never returned to operation. The Northern industries that had grown extremely profitable and dependent upon the war, churning out uniforms, accouterments, artillery pieces and ammunition, no longer had a customer.

Although the South was undergoing reconstruction and the nation was moving to put the war in the past, and some Americans who lost everything were seeking to start afresh in the West. Like the servicemen and women of the current conflicts, Union and Confederate veterans alike were dealing with the same lingering effects of the combat trauma they had endured. While life for them was moving on, they were drawn to their comrades-in-arms seeking the friendship they shared while in uniform. In 1866, Union veterans began reuniting, forming a long-standing veterans organization (which would last until 1956 when the last veteran died) that would be known as the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). Similarly, Confederate troops would reunite, but wouldn’t formally organize until 1889 with the United Confederate Veterans.

While the country was still engaged in the war, the spouses and mothers of troops, along with their local communities, honored those killed in the war—the scant few that were returned home for burial—by decorating their graves. Freed slaves (known as Freedmen) from Charleston, South Carolina, knew of a tragedy that took place at a prisoner of war (POW) camp where there were more than 250 Union soldiers who had died in captivity and had been buried in unmarked graves. The Freedmen, knowing about the graves, organized and gathered at the burial site to beautify the grounds in recognition of the sacrifices made by the soldiers on their behalf. On May 1, 1865, nearly 10,000 Freedmen, Union veterans, school children and missionaries and black ministers, gathered to honor the dead at the site on what would come to be recognized as the first Memorial Day.

“This was the first Memorial Day. African-Americans invented Memorial Day in Charleston, South Carolina. What you have there is black Americans recently freed from slavery announcing to the world with their flowers, their feet, and their songs what the War had been about. What they basically were creating was the Independence Day of a Second American Revolution.” – historian David W. Blight

- Gettysburg Reunion: GAR members and veterans of The Battle of Gettysburg encamped at the gathering (source: Smithsonian Institute).

- Veterans of General George Pickett gather at Gettysburg’s Bloody Angle during the 50th anniversary of the battle (source: Smithsonian Institute).

- To mark the 50th anniversary of the Civil War this group of Confederate veterans reenacted “Pickett’s Charge” at Gettysburg during the 1913 reunion (source: Smithsonian Institute).

The largest gathering of Civil War veterans took place in 1913 at the Gettysburg battlefield, marking the 50th anniversary of this monumental battle. Soldiers from all of the participating units converged on the various sites to recount their actions, conduct reenactments, and to simply reconnect with their comrades. Heavily documented by photographers and newsmen alike, the gathering gave twentieth century Americans a glimpse into the past and the personal aspects of the battles and the lifelong impact they had on these men. By the 1930s, the aged veterans numbers had dwindled considerably yet they still continued to reunite. In one of these last gatherings, Confederate veterans recreated their battle cry, the Rebel Yell, for in this short film (digitized by the Smithsonian Institute).

- Obverse and reverse of a GAR medal from 1886 (source: OMSA database).

- This vintage cabinet photo shows a Civil War veteran proudly displaying his GAR medal.

The Militaria Collecting Connection

While collecting Civil War militaria can be quite an expensive venture, items related to these veterans organizations and reunions are a great alternative. One item that is particularly interesting, the GAR membership medal, was authorized for veterans to wear on military uniforms by Congressional action. The medals or badges were used to indicate membership within the organization or to commemorate one of its annual reunions or gatherings.

Over the years following the 1913 reunion, veterans and their families increasingly honored those killed during the war around the same time each year. As early as 1882, the day to honor the Civil War dead (traditionally, May 30) was also known as Memorial Day. After gaining popularity in the years following World War II, Memorial Day became official as congress passed a law in 1967, recognizing Memorial Day as a federal holiday. The following year, on June 28, the holiday was moved to the last Monday of May, creating a three-day weekend.

This Memorial Day, rather than committing the day to squeezing in one last waterskiing pass on the lake or grilling up a slab of ribs, head out to a cemetery (preferably a National Cemetery if you are in close enough proximity) and decorate a veteran’s grave with a flag and spend time in reflection of the price paid by all service members who laid down their lives for this nation. Note the stark contrast to the violence experienced on the field of battle as you take in the stillness and quiet peace of the surroundings, observing the gentleness of the billowing flags.

The Militaria Collector’s Search for the White Whale

The hunt. The search. The quest for the prize. Seeking and finding the “Holy Grail.” We collectors tend to describe the pursuit of those elusive pieces that would fill a glaring void in our collection with some rather lofty terms or phrases.

We wear our collection objectives on our sleeves while pouring through every online auction listing, or burning through countless gallons of gasoline while making the rounds from one garage or yard sale to the next. Antiques store owners (whom we think are our friends) have our lists of objectives to be on the lookout for.

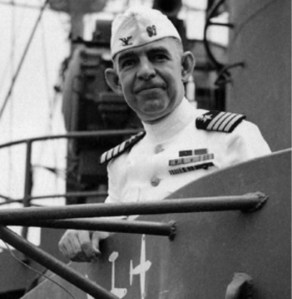

A close-up of the USS Astoria’s first commanding officer, Captain George C. Dyer, wearing his choker whites and the rare white garrison cover (source: Brent Jones Collection).

Militaria collectors (any collector, for that matter) thrive on the hunt and feed off the adrenaline rush that comes from achieving each victory as they locate and secure the piece that has seemingly evaded every search effort. Hearing that they’ve missed an opportunity by seconds due to some other collector beating them out only fuels their passion. Losing an auction because they tried to play conservatively with their bidding propels them through the twists, turns, hills and valleys of the emotional roller coaster.

Searching for militaria can be an exhausting endeavor. For the last two years, I’ve been searching for a piece and while I can’t say that I’ve been through these scenarios, I did manage to feel an amount of elation when I achieved success with my objective.

This shot shows Captain George C. Dyer departing the Astoria wearing his dress white uniform and the white garrison cover (source: Brent Jones Collection).

I’m not wanting to repeat myself (which I do quite often, considering all of my previous posts), but let me state that I do not consider myself any manner of expert on military history or militaria. I assert that I have a broad-based knowledge on a narrow scope of U.S. military history (20th century) with a primary focus on the U.S. Navy. So when I discovered an item that I had previously never knew existed, I was quite curious and subsequently needed to obtain it.

An acquaintance (who had contributed photos for my first book that I published in 2009) has a website that is the public face of his extensive and invaluable research on the USS Astoria naval warships. On this site, I noticed some new images that he had recently obtained and published showing the first commanding officer, Captain George C. Dyer, of the USS Astoria CL-90 turning over command of the ship and departing amidst his change of command ceremony.

Pictured here with an early WWII chief radioman’s eight-button, dress white uniform jacket, the (yellowing and aged) white garrison cover is a bit more distinguishable from a khaki variant.

For the ceremony, the ship’s crew is turned out in their summer white dress uniforms. All appeared to be normal until I spied the unusual uniform item – the commanding officer was wearing a garrison cover (hats in the Navy or Marine Corps are known as covers). Affectionately known as a (excuse the crass term) “piss cutter,” I knew that the garrison was available for use with the (aviator) green, khaki, (the short-lived) gray and the blue uniforms, but I had never seen a photo of this white variety. Garrison covers are not particularly stylish, but due to their lightweight and soft construction, they are considerably more comfortable than the traditional combination cover (visor caps) alternatives.

A Garrison Comparison: at the top is the white garrison (compared with a WWII khaki) demonstrating that, though it is yellowed, it is the rare white cap.

Plentiful and very readily available, the khaki versions are quite frequently listed or for sale at antiques stores and garage sales. The green, gray and blue garrisons are a little bit more rare yet turn up with some regularity. The white garrison is the great, white whale. Considering that it was not well-liked in the fleet during the war (when it was issued), it is now extremely rare for collectors seeking to possess all of the uniform options. The white garrison is truly the white whale among World War II navy uniform items.

Seeing this hat in the photos fueled my quest to obtain one for my collection. The very first one I had ever seen listed anywhere became available last week at auction. I placed my bid at the very last second and was awarded with the holy grail. Yesterday, the package arrived and was both elated and saddened as my quest was fulfilled.

No longer needing to hunt for this cover, I feel as though I have lost my way… a ship underway without steerage. What am I saying? I have plenty of collecting goals un-achieved!

A Temporary Break From Tradition: Navy Shoulder Sleeve Insignia

Two examples of the correct placement of the Navy SSI, worn during WWII. Shown on these uniforms is the Amphibious Forces Personnel patch.

Dress uniforms of the United States Navy have been remained relatively consistent, holding fast to their traditional appearance since the mid-nineteenth century. From the pullover jumper with the flap and neckerchief to the beautifully embroidered eagle and specialty marks of the rate badge, the uniform seldom strays too far from its unique appearance.

There have been some departures or design variances that left traditionalists scratching their heads, wondering why the navy brass seemingly tried to make the naval uniforms take on traits from the sibling military branches.

One of the most significantly negative changes occurred during the 1970s when the jumper uniforms (both service dress versions – blues and whites) were summarily eliminated in favor of the vanilla-stylings of a simple button-down white shirt and black trousers (known as “salt and peppers”) with a combination cover. The change was short-lived as the jumpers were re-instituted in the early 1980s and have been in use since. Due to their unpopularity, these uniforms draw little or no interest from collectors.

Another, less impactful change that was applied to the navy dress uniform was far less sweeping and seemed to set apart specific naval components rather than provide unity across the naval services. During World War II, with the ranks swelling to all-time highs, obviously necessary due to the manning requirements of a nearly 6,100-ship fleet, the specialized nature of certain functions had emerged into the spotlight, drawing significant attention from the rest of the armed forces and American public. The need to set these services apart arose, somewhat organically, as units began to adopt uniform concepts from the other branches.

Shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) had been in use across the U.S. Army as a means for identifying which units soldiers belonged to, the Navy had never previously authorized similar markings for their uniforms (other than hat tallies for the blue flat or “Donald Duck” hats).

The uniform shirt bore only rate and rating as well as distinguishing marks at the onset of World War II. However, by 1943, sailors in the minesweeper community had begun affixing an embroidered red, white and blue circular-designed patch (representing a painted device seen aboard mine sweeper vessels) to their left shoulders, directly above the rate badge. The commanding officer of the minesweeper, USS Zeal (AM-131) seeking to determine if such a patch was authorized for wear, sent a letter to navy brass. The Chief of Naval Personnel responded on June 24, 1943 that the patch was not permitted for wear. Despite the rejection, sailors continued to wear the SSI.

As the war progressed, other naval components began to adopt shoulder patches and approval from the higher-ups for these patches began to trickle down.

Officially Approved U.S. Navy Shoulder Sleeve Insignia (with approval date):

- Amphibious Forces Personnel – January 1944

- Motor Torpedo Boat Personnel (PT Boat) – September 1944

- Minecraft Personnel – December 1944

- Naval Construction Battalion (Sea Bees) – October 1944

- Approved for wear in early 1944, this Naval Amphibious Forces patch has a nearly–identical U.S. Army counterpart (the same gold emblem instead on a field of blue) was the first of a handful of Navy SSI (Image source: eBay).

- This Motor Torpedo Boat Personnel (PT Boat) patch was approved for wear in September, 1944 (source: eBay).

- Minecraft Personnel SSI from 1944.

- Authorized “SEABEES” patch (source: National WWII Museum).

- This variation of the authorized SeaBees patch also originates during WWII but incorporates the abbreviation for the unit.

Unauthorized SSI:

- Amphibious Forces (Gator) Patch

- Minesweeper Personnel Patch

- Harbor Defense Personnel Patch

- Mosquito Boat Patch

- This unauthorized Naval Amphibious Forces patch started appearing sometime in 1943 (source: eBay).

- The navy disallowed this Mine Sweeper Personnel patch in 1943, yet that did not prevent its use in the fleet during the war. (source: LJ Militaria).

- Though unauthorized, this Harbor Defense Personnel (also known as Harbor Net Tender) is for wear on the dress blue uniform (source: eBay).

- Manufactured for wear on dress blues, this is a fine example of the un-approved Mosquito Boat Personnel patch (source: eBay).

- This white variant of the unauthorized Mosquito Boat Personnel patch has never been worn on a uniform (source: eBay).

On January 17, 1947, the Navy once again embraced tradition and officially abolished all shoulder sleeve insignia.

Due to their considerable production, the authorized SSI patches are plentiful and readily affordable for militaria collectors. The unofficial insignia will be more challenging to locate and in some cases be considerably more expensive to acquire.

Research Resources:

- Marks, Specialty Marks and Distinguishing Marks of the Sea Services (U.S. Militaria Forum discussion topic)

- U.S. Navy Rating Badges, Specialty Marks & Distinguishing Marks 1885-1982 (Stacey, John A., paperback)

- Complete Guide to United States Navy Medals, Badges and Insignia: World War II to Present (Thompson, James G., paperback)