Category Archives: Other Militaria

The Bizarre and the Oddities of Militaria

While there are certainly traditional military items that folks collect such as uniform items and weapons, some people aren’t satisfied with the status quo of militaria collecting. It takes a person with a bit of a twisted perspective to seek out the strange or odd items or to possess the ability to see the contextual vantage point of the militaria collector.

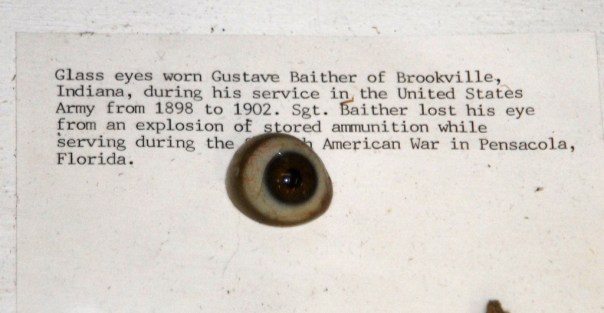

At first glance, Sgt. Gustave Blaither’s Spanish American War Uniform Group (located at the Indiana Military Museum) seems to be a normal SpanAm War group display

Suppose that there are collectors who focus on field surgeon equipment from the Civil War era. A collection might include medicines and physician’s guides, but it could also include surgical implements. Aside from the traditional scalpel set, expect to see an array of macabre bone saws and tourniquets.

Another example of what some folks might deem as odd militaria could be a collection of named (meaning, engraved with the veteran’s name) Purple Heart medals awarded to service members who were killed in action (KIA). While this may also seem dark, most collectors of Purple Hearts (at least that I’ve encountered) see this as a way to preserve history and share the story of those who made the ultimate sacrifice for our nation. Whenever I glimpse one of these medals, I am overwhelmed when I consider the price that was paid by an American.

One of the most bizarre items of militaria that I have personally seen was at the Indiana Military Museum located in Vincennes, Indiana. Among the wonderful displays is a group of items that belonged to soldier who served during the 1898 war with Spain.

It seems that he suffered a debilitating head wound when some stored ammunition exploded, emitting a destructive array of metal and wood debris. The result of the wounds sustained by Sergeant Gustave Baither was the traumatic loss of one of his eyes.

Closer inspection of Blaither’s collection yields this odd gem – his glass eye.

In my own collection, I have preserved an item that to the untrained eye would be indistinguishable as something pertaining to military use. However, this piece is a part of naval and seafarer tradition spanning centuries of sea-going service. Hand-made from a section of 1-1/2-inch fire hose, a piece of a broom handle, electrical heat-shrink tape and wrapped with braided shotline (used during Underway Replenishment), the shillelagh is a centerpiece of the equator crossing initiation ceremony known as Wog Day.

This “Wog Dog Correction Tool”, also known as a “Shillelagh, ” was made and used aboard the USS Camden (AOE-2) during the 1989 WestPac deployment.

My shillelagh, made during my last sea deployment in 1989, was used to provide much-needed correction to the pollywogs (those who hadn’t crossed the equator) by applying gentle (ok… maybe not-so-gentle) swats to their posterior region as they crawl across the ship’s decks. Upon completion of that cruise, my shillelagh was tossed into my closet where it has remained, almost forgotten… that is until my kids wanted to learn about Navy traditions.

What unusual items are in your collections?

Decorating Sacrifice: Honoring Our Fallen

Most Americans have no connection Memorial Day, their heritage or to the legacy left behind by those who gave their lives in service to this country.

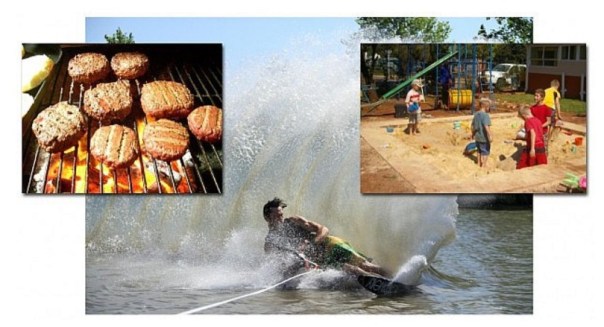

This weekend, we Americans are being inundated with myriad auditory treats, such as the sound of burgers and hot dogs sizzling on the barbecue grill, the roar of the ski boats tearing across the lake, the rapid-clicking of fishing reels spinning, or the din of children playing in the backyard. All of this points to the commencement of summer and the excitement-filled season of outdoor activities, vacations and fun. The bonus is that we get to extend this weekend by a day and play a little harder as that’s what this weekend is all about!

With the opening volleys of artillery (the Confederates firing on Fort Sumter) in the early morning hours of Friday, April 12, 1861, a war of the bloodiest nature commenced within the confines of what was known as the United States of America, but which was anything but united. The division of the states had been years in the making as the founding fathers could hardly agree on the slavery issue when trying to establish a single Constitution that would bind the individual states together as one unified nation. The division led to an all-out conflict—a war that would pit brother against brother and father against son—that wouldn’t cease until almost exactly four years later (at Appomattox on April 10, 1865) and three-quarters of a million Americans were dead (the number was recently revised, up from 618,000, by demographic historians).

In the days, weeks, months and years that followed, the sting of the Civil War would linger as families suffered the loss of generations of men. The Southern States where battles took place had cities that were obliterated. The agricultural Industry was devastated. The business operation surrounding the king crop of the south, cotton, heavily dependent upon slave labor, had to be completely revamped. Many plantations never returned to operation. The Northern industries that had grown extremely profitable and dependent upon the war, churning out uniforms, accouterments, artillery pieces and ammunition, no longer had a customer.

Although the South was undergoing reconstruction and the nation was moving to put the war in the past, and some Americans who lost everything were seeking to start afresh in the West. Like the servicemen and women of the current conflicts, Union and Confederate veterans alike were dealing with the same lingering effects of the combat trauma they had endured. While life for them was moving on, they were drawn to their comrades-in-arms seeking the friendship they shared while in uniform. In 1866, Union veterans began reuniting, forming a long-standing veterans organization (which would last until 1956 when the last veteran died) that would be known as the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). Similarly, Confederate troops would reunite, but wouldn’t formally organize until 1889 with the United Confederate Veterans.

While the country was still engaged in the war, the spouses and mothers of troops, along with their local communities, honored those killed in the war—the scant few that were returned home for burial—by decorating their graves. Freed slaves (known as Freedmen) from Charleston, South Carolina, knew of a tragedy that took place at a prisoner of war (POW) camp where there were more than 250 Union soldiers who had died in captivity and had been buried in unmarked graves. The Freedmen, knowing about the graves, organized and gathered at the burial site to beautify the grounds in recognition of the sacrifices made by the soldiers on their behalf. On May 1, 1865, nearly 10,000 Freedmen, Union veterans, school children and missionaries and black ministers, gathered to honor the dead at the site on what would come to be recognized as the first Memorial Day.

“This was the first Memorial Day. African-Americans invented Memorial Day in Charleston, South Carolina. What you have there is black Americans recently freed from slavery announcing to the world with their flowers, their feet, and their songs what the War had been about. What they basically were creating was the Independence Day of a Second American Revolution.” – historian David W. Blight

- Gettysburg Reunion: GAR members and veterans of The Battle of Gettysburg encamped at the gathering (source: Smithsonian Institute).

- Veterans of General George Pickett gather at Gettysburg’s Bloody Angle during the 50th anniversary of the battle (source: Smithsonian Institute).

- To mark the 50th anniversary of the Civil War this group of Confederate veterans reenacted “Pickett’s Charge” at Gettysburg during the 1913 reunion (source: Smithsonian Institute).

The largest gathering of Civil War veterans took place in 1913 at the Gettysburg battlefield, marking the 50th anniversary of this monumental battle. Soldiers from all of the participating units converged on the various sites to recount their actions, conduct reenactments, and to simply reconnect with their comrades. Heavily documented by photographers and newsmen alike, the gathering gave twentieth century Americans a glimpse into the past and the personal aspects of the battles and the lifelong impact they had on these men. By the 1930s, the aged veterans numbers had dwindled considerably yet they still continued to reunite. In one of these last gatherings, Confederate veterans recreated their battle cry, the Rebel Yell, for in this short film (digitized by the Smithsonian Institute).

- Obverse and reverse of a GAR medal from 1886 (source: OMSA database).

- This vintage cabinet photo shows a Civil War veteran proudly displaying his GAR medal.

The Militaria Collecting Connection

While collecting Civil War militaria can be quite an expensive venture, items related to these veterans organizations and reunions are a great alternative. One item that is particularly interesting, the GAR membership medal, was authorized for veterans to wear on military uniforms by Congressional action. The medals or badges were used to indicate membership within the organization or to commemorate one of its annual reunions or gatherings.

Over the years following the 1913 reunion, veterans and their families increasingly honored those killed during the war around the same time each year. As early as 1882, the day to honor the Civil War dead (traditionally, May 30) was also known as Memorial Day. After gaining popularity in the years following World War II, Memorial Day became official as congress passed a law in 1967, recognizing Memorial Day as a federal holiday. The following year, on June 28, the holiday was moved to the last Monday of May, creating a three-day weekend.

This Memorial Day, rather than committing the day to squeezing in one last waterskiing pass on the lake or grilling up a slab of ribs, head out to a cemetery (preferably a National Cemetery if you are in close enough proximity) and decorate a veteran’s grave with a flag and spend time in reflection of the price paid by all service members who laid down their lives for this nation. Note the stark contrast to the violence experienced on the field of battle as you take in the stillness and quiet peace of the surroundings, observing the gentleness of the billowing flags.

Remembering (and Collecting) the USS Maine!

In the decades following the American Civil War, the United states was busy dealing with the reconstruction of the South, expansion into the Western states and territories, adding new stars to the blue canton of the national ensign (i.e. the addition of states to the Union), the influx of the destitute of Europe seeking to benefit from the Land of Opportunity and all the trefoils of a growing nation. Few Americans set their eyes upon the instability of governments beyond the borders and shores as the nation surpassed her first century of existence. Life, though fraught with the many diverse challenges of the time, was good.

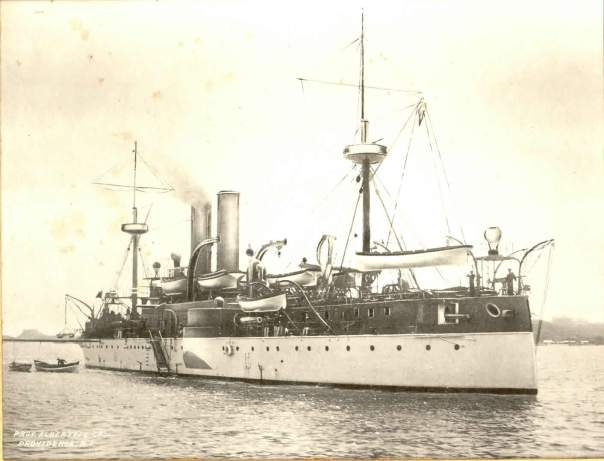

USS Maine ACR-1 – Havana Harbor, 1898

In the latter half of nineteenth century, the American navy commenced a dramatic technological transformation from wooden-hulled sailing sloops and frigates, followed by ironclads and paddle-wheels, to steel coal-fired steam warships. Naval gunnery was advancing and the U.S. leadership was following the advances being made by the British navy that had necessitated a radical departure from the ship design convention (of the time) in order to take full advantage of the new capabilities. The U.S. Navy, had been fully committed to the designs of the ironclad Monitor and many of the European navies adopted similar designs following the American’s success with them during the Civil War. With technology advancing at such a rapid pace and the need for a global naval reach, the Monitor was rendered obsolete, in favor of larger, more powerful ships with greater sailing range which would come to be known as pre-Dreadnoughts.

In the 1880s, the U.S. Navy began planning and designing their first pre-Dreadnought armored cruisers. By 1886, the Navy funded the first two ships of the new design, the lead ship, USS Maine and her (closely-related) sister, the USS Texas. The Maine’s keel was laid down on October 17, 1888 at the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard and wouldn’t be completed for nearly seven years. She was commissioned and placed into service on September 17, 1895 and following sea trials and fitting out, was assigned to the North Atlantic Squadron for service.

As the 1890s were drawing to a close, a spark in the tinderbox of the Cuban independence movement began to be fanned by U.S. financial influence. American capitalism and politics had been involved in Cuba for the past few decades investing heavily in the sugar cane and tobacco industries, driving economic transformation of the Spanish-owned island and fueling unrest among the citizens. American popular sentiment, led by a pro-liberation agenda that was propagandized throughout the newspapers of the day, was growing in favor of intervening against the Spanish government. In January of 1898, a pro-Spanish riot erupted in Havana which prompted the American Consul-General to request assistance to protect U.S. citizens and business interests.

Sailing into Havana Harbor at the end of January, the USS Maine provided a menacing reminder of the United States’ commitment to protect her interests. In addition, her presence could have appeared to the Spanish loyalists as a threat to their sovereignty. Perhaps the revolutionaries saw the ship as an opportunity to draw the United States into a conflict with Spain that could result in the ouster of their oppressive overseers. Regardless of the stance of the two opposing sides, the Maine’s presences added to the already increasing tension.

Aboard ship, the crew was going about settling down for the night on February 15, 1898. Twenty minutes before taps and lights out, the shipboard routines were winding down. Liberty boats had returned to the ship and had been secured for the night. Suddenly and without warning, a massive explosion rocked the forward part of the ship as 5.1 tons of gunpowder ignited. In a matter of seconds, the Maine was sitting on the bottom of the harbor and more than 260 of her crew (of 355 officers and men) were dead.

Galax leaf wreaths decorate the coffins containing the dead of the Maine on December 28, 1899.

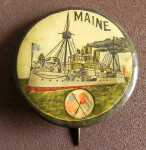

Following a formal investigation and inquiry into the cause of the explosion, the cause was determined to be the result of a mine (though no supporting evidence existed). The slogan of the day, “To hell with Spain! Remember the Maine” could be found in print and plastered across buttons and pins as the American public began to rally to the cause. Following the publication of the findings, a media blitz of inflaming editorials and exaggerated facts ultimately led to an April 21, 1898 formal declaration of war against Spain.

- America fights back. This button demonstrates the angry sentiments of the day with, “Remember the Maine – Gosh Darn Yer” (source: eBay image).

- More subdued, the message is still clear with regards to the Maine’s sinking. Note the crossed American and Cuban flags (source: eBay image).

- USS Maine cast iron coin bank (source: eBay image).

- Several versions of this candy dish are readily available in antique shops and online auction listings. I have found several colors – clear, two shades of green, and cobalt blue (source: eBay image).

After resounding victories in Manila Bay (in the Philippines) and San Jaun Hill (Puerto Rico), the Spanish pursued peace with the United States by the middle of July, 1898. The peace treaties were signed in Paris on August 12, 1898, relinquishing all rights and claims to the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

With the guns now silent and the U.S. reverting to their isolationist stance, the rallying cry of “Remember the Maine” began to fade from the forefront of the U.S. populace. This was not so with Navy leadership who were still seeking definitive facts surrounding her sinking. In 1910, Navy engineers began constructing a cofferdam surrounding the shallow-water wreck of the ship. After the harbor waters receded from the wreck, investigators poured over every inch of the hulk. With no conclusive evidence uncovered and the bodies of the crewmen were removed for burial in the U.S. (at Arlington National Cemetery), the ship was refloated, towed out to sea and scuttled.

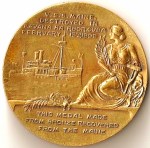

- This outstanding example of a USS Maine medallion commemorates the ship and the Pittsburgh, PA memorial that was dedicated in 1914. The inscription on the obverse reads, “U.S.S. Maine, Destroyed in Havana Harbor, Cuba, February 15th, 1898.This medal made from bronze recovered from the Maine.”

- The inscription on the medallion’s reverse reads, “Issued by the general committee of the fifteenth annual reunion of the army of the Philippines, Cuba and Porto Rico, in memory of our deceased comrades and the dedication of the Maine Memorial. Pittsburgh, PA | September 16th, 1914.”

- This rare pin calls for Americans to avenge the sinking of the Maine (source: eBay image).

- Remember the Maine Medallion obverse showing Admiral Dewey (source: eBay image).

- This tally (from the BB-10) recently recently sold for under $200 (source: eBay image).

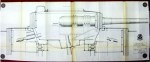

- USS Maine Turret Technical Drawing USS Maine turret technical drawing (source: eBay image).

Bell of the USS Maine, broken in half by the 1898 explosion, attached to the door of the memorial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Several pieces of the ship were removed at the time of the 1910-1912 investigation including munitions, guns, pieces of her superstructure and mast and other items that would serve as central components of memorials that were being constructed around the country. Commemorative medallions were cast from metal retrieved from her screws as Americans renewed their commitment to remember the Maine.

Four years following the devastating loss of the cruiser, the U.S. Navy commissioned the USS Maine (BB-10), the lead ship of three-ship class of battleships which also included the USS Missouri (BB-11) and USS Ohio (BB-12). The second USS Maine would proudly carry the name and legacy in Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet and through World War I. Her 18-year career ended with her May, 1920 decommissioning. The Maine name wouldn’t sail again until 1994 when the Navy launched the 16th Ohio-class Trident submarine, USS Maine (SSBN-741) which is currently homeported in Bangor, Washington.

More than 110 years later, the stricken USS Maine resonates with a minute segment of collectors. While very few items or artifacts originating from the ship surface within the marketplace, memorial pieces are readily available.

Inscription on the Havana USS Maine monument:

“El Pueblo De La Isla De Cuba Es Y De Derecho Debe Ser Libre E Independiente.” Resolucion con junta del Congreso de los Estados Unidos de Norteamerica De 19 de April De 1898.

“The people of the island of Cuba are and of right ought to be free and independent.” Congressional joint resolution with the United States of America from April 19, 1898.