Category Archives: World War I

Drawing in Recruits: Posters and Broadsides

Tonight, as I was finishing up some research for one of my genealogy projects, I found myself clicking through a series of online auction listings of militaria that would look absolutely fantastic hanging on the walls of my “war room.” My mind began to wander with each page view, imagining the various patriotic renderings, designed to inspire the 1940s youth to rush to their local recruiter to almost single-handedly take on the powers of the Axis nations.

Originally created for Ladies Weekly in 1916, the iconic image of Uncle Sam was incorporated into what is probably the single, most popular recruiting poster that began its run during WWI (source: Library of Congress).

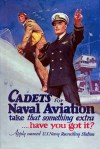

Rather than focusing on the raging war in Europe, this Charles Ruttan-designed poster demonstrates the career and travel opportunities.

Recruiting posters are some of the most collected items of militaria as their imagery conjures incredible emotional responses, such as intense national sentiment, inflamed hatred of the new-found enemy or a sense of call of duty. The colorful imagery of these posters inspires considerable interest from a wide range of collectors, in some cases driving prices well into four-digit realms.

Most Americans are familiar with the iconic imagery of Uncle Sam’s “I Want YOU for the U.S. Army” that was created and used in the poster by James Montgomery Flagg, making its first appearance in 1916, prior to the United States’ entry into World War I. While this poster is arguably the most recognizable recruiting poster, it was clearly not the first. Determining the first American use of recruiting posters, one need not look any further than the Revolutionary war with the use of broadsides, one of the most common media formats of the time.

The use of broadsides, some with a smattering of artwork, continued to be utilized well into (and beyond) the Civil War with both the Army and Navy seeking volunteers to fill their ranks. With the advancement of printing technology and the ability to incorporate full color, the artwork began to improve, adding a new twist to the posters, providing considerable visual appeal. By the turn of the twentieth century, well-known artists were commissioned to provide designs that would evoke the response to the geopolitical and military needs of the day.

- Known as a broadside, this poster mentioned that able-bodied men that were not headed for Army ranks would be enlisted into Naval service.

- This is a beautiful example of a Revolutionary War broadside is recruiting soldiers for service in General Washington’s Army for Liberties and Service in the United States (source: ConnecticutHistory.org).

Adding to the appeal for many non-militaria collectors is artist cache associated with many of the recruiting poster source illustrations. The military brought in the “big guns” of the advertising industry’s graphic design, tapping into the reservoir of well-known artists; if their names weren’t known, their stylings had permeated into pop culture by way of ephemera and other print media advertising. In addition to James Flagg, some of the most significant (i.e. most sought-after and most valuable) Navy recruiting posters were designed by notable artists such as:

- Howard Chandler Christy’s famous “Christy Girl” poster from World War I.

- This sailor extends his hand to would-be recruits encouraging them to climb aboard and join the fight. McClelland Barclay incorporated his advertising industry experience in graphic-design and style into these recruiting posters.

- The Naval Construction Battalion (CB or “Sea Bees”) was proposed in 1941 and established immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack. This poster (illustrated by John Falter) was used to attract journeymen construction tradesmen who would build all of the bases and airfields used to push the Japanese back to their homeland, one island at a time.

- Another McClelland Barclay poster showing a naval aviator climbing into his open-cockpit aircraft with a battleship mast and superstructure showing in the background.

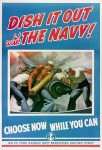

- These sailors rapidly load the naval gun as they are actively engaged in combat. This imagery (by McClelland Barclay) was designed to fan the flames of nationalism and nudge those seeking to avenge the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Sadly, with my limited budget and my unwillingness to horse-trade any of my collection, these posters are somewhat out of my reach. It goes without saying that condition and age along with desirability have direct impact on value and selling prices. Some of the most desirable posters of World War II can sell for as much as $1,500-$2,000. For the collector with deeper pockets, Civil War broadsides can be had for $4,500-$6,000 when they become available. I have yet to locate any of the recruiting ephemera from the Revolutionary War, so I wouldn’t begin to speculate the price ranges should a piece come to market.

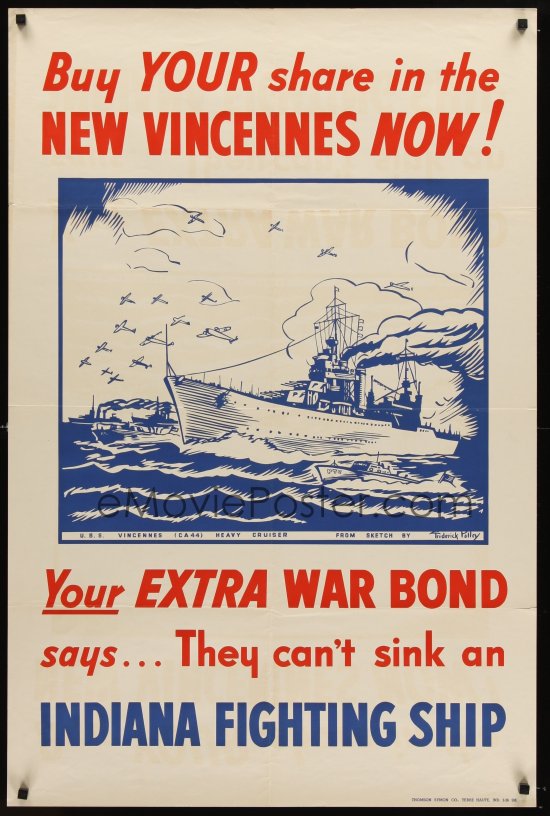

The citizens of a small Indiana town (Vincennes) raised enough money through a successful bond drive to meet the Secretary of the Navy’s financial requirement which resulted in the already under construction light cruiser (CL-64) to be named Vincennes.

Discouraged as I may be in my quest to secure one of these treasured prints, I may be better off seeking quality reproductions to adorn the vertical white-space of my war room. However, a few years ago I received a reproduced war-bond drive poster – the original was created to encourage Hoosiers to buy bonds to name a new cruiser to honor the (then) recently sunk USS Vincennes.

Note: All images not sourced are provided courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command

Calculated Risks: Bidding on Online Auctions that Contain Errors

Regardless of how much knowledge you may possess, making good decisions about purchasing something that is “collectible” can be a risky venture ending in disappointment and being taken by, at worst, con-artists or at best, a seller who is wholly ignorant of the item they are selling. Research and gut-instinct should always guide your purchases for militaria. Being armed with the concept that when something is too-good-to-be-true, it is best to avoid it. I recently fell victim to my own foolishness when I saw an online auction listing for an item that was entirely in keeping with what I collect.

I am very interested in some specific areas of American naval history and one of my collecting focus centers around a select-few ships and almost anything (or anyone) who might have been associated with them. One of those ships (really, four: all named to honor the Revolutionary War battle where American George Rogers Clark was victorious in Vincennes, IN), the heavy cruiser USS Vincennes (CA-44) is one in particular that I am constantly on the lookout for.

- The auction listing is innocuous; albeit accurate. However, the details are where this seller’s words are misleading and troublesome.

- Note in the description that the seller lists specifics about the book (nothing the title, author and edition). Sadly, this is a farse.

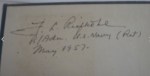

- There were two factors that led me to purchase this book: Admrial Riefkohl’s signaturem that it was in, what I consider to be one of the most accurate accounts of the Savo Island battle.

In early September (2016), a listing for an item that surfaced in one of my saved searches results, caught my attention on eBay. The auction description made mention of a book, Savo: The incredible Naval Debacle Off Guadalcanal, that happens to be one of the principle, reliable sources for countless subsequent publications discussing the August 8-9, 1942 battle in the waters surrounding Savo Island. Though I read this book (it was in our ship’s library) years ago, it is a book that I wanted to add to my collection but until this point, never found a copy that I wanted to purchase. What made this auction more enticing was that this book featured a notable autograph on the inside cover. In viewing the seller’s photos, I noted that the dust jacket was in rough shape but the book appeared to be in good condition (though the cover and binding were not displayed). There were no bids and the starting price was less than $9.00.

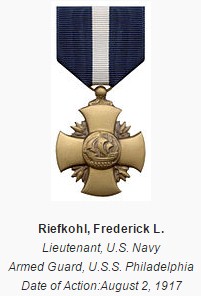

Riefkohl was awarded the Navy Cross medal for actions performed aboard the USS Philadelphia against German submarines during WWI convoy escort operations (see the test of the accompanying citation below).

I have been a collector of autographs and have obtained several directly from cultural icons (sports stars, actors, musicians) but my favorites are of notable military figures (recipients of the Medal of Honor [MOH] and other servicemen and women) who distinguished themselves in service to our country. The signature in this book featured a retired naval officer who was the recipient of the Navy’s highest honor, the Navy Cross (surpassed only by the MOH) and who played a significant role in the Battle of Savo Island as he was the commanding officer of the heavy cruiser, USS Vincennes (CA-44) and the senior officer present afloat (SOPA) for the allied group of ships charged with defending the northern approaches (to Savo and Tulagi islands). Frederick Lois Riefkohl (then a captain) commanded the northern group which consisted of four heavy cruisers; (including Vincennes) USS Quincy (CA-39), Astoria (CA-34) and HMAS Canberra (D33).

By all accounts, the Battle of Savo Island (as the engagement is known as) is thought to be one of the worst losses in U.S. naval history (perhaps second only to the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor) as within minutes of the opening salvos by the Japanese naval force, all four allied ships were left completely disabled and sinking (all would succumb to the damage and slip beneath the waves in the following hours). Though the loss was substantial, the Japanese turned away from their intended targets (the allied amphibious transport ships that were landing marines and supplies on Guadalcanal and Tulagi) missing a massive opportunity to stop the beginnings of the allied island-hopping campaign. The First Marine division was permanently entrenched on these islands, and would drive the Japanese from the Solomons in the coming months.

Captain Frederick Lois Riefkohl (shown here as a rear admiral).

Captain Riefkohl was promoted to Rear Admiral and retired from the Navy in 1947 having served for more than 36 years. He commanded both the USS Corry (DD-334) and the Vincennes and having served his country with distinction, the Savo Island loss somewhat marred his highly successful career.

As I inspected the book, there were a few aspects that gave me reason for pause. First, the seller described the book as “SAVO by Newcomb 1957 edition” which left me puzzled. Secondly, the Admiral included a date (“May 1957”) with his signature. Recalling that Newcomb’s book was published in 1961 ( See: Newcomb, Richard Fairchild. 1961. Savo. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.), I was a bit dismayed by the four-year discrepancy between the date of the autograph and (what the seller determined to be the) first edition published date. I wondered, “how did he determine this date and where did he find this information?” I noted that there was no photograph of the book’s title page accompanying the auction.

I decided to take a gamble that at worst, would result in me spending a small sum of money for an autograph that I wanted for my collection and at best was merely a fouled up listing by an uninformed seller. I pulled the trigger and my winning bid of $8.99 had the book en route (with free shipping, to boot)!

The dust jacket is in very rough shape with tears, creases, cracks, shelf wear and dog-ears. The cover art is fairly intense in conveying what took place in the battle.

The confirmation that I didn’t want; this book turned out to be”Death of a Navy” which isn’t worth investing time to read as it is known to be a rather erroneous work.

Nearly two weeks later, the package arrived. I reservedly opened the packaging and freed the book from the layers of plastic and bubble wrap. I inspected the ragged dust jacket and removed it to see the very clean cover which didn’t seem to match. I opened the book and viewed Riefkohl’s autograph which appeared to match the examples that I have seen previously. I turned to the title page and confirmed my suspicions. Death of a Navy by an obscure French author, Andrieu D’Albas (Captain, French Navy Reserve). “Death” is not worthy enough to be considered a footnote in the retelling of the Pacific Theater war as D’ Albas’ work is filled with errors. By 1957 (when this book was published), most of what was to be discovered (following the 1945 surrender) from the Japanese naval perspective was well publicized before the start of the Korean War. It is no wonder why Andrieu D’Albas published only one book.

- Death of a listing. This acquisition turned out to be a partial dud.

- Removing the dust jacket, the cover didn’t seem to match the dust jacket.

My worst-case scenario realized, I now (merely) have the autograph of a notable U.S. naval hero in my collection. While I could have gone with my gut feelings about the auction listing, having this autograph does offset my feelings of being misled (regardless of the seller’s intentions).

Admiral Riefkohl’s signature appears to be authentic leaving me semi satisfied in that I obtained a great autograph for my collection.

Riefkohl’s Navy Cross Citation:

The Navy Cross is awarded to Lieutenant Frederick L. Riefkohl, U.S. Navy, for distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commander of the Armed Guard of the U.S.S. Philadelphia, and in an engagement with an enemy submarine. On August 2, 1917, a periscope was sighted, and then a torpedo passed under the stern of the ship. A shot was fired, which struck close to the submarine, which then disappeared

Collecting Militaria: Historical Preservation or War Glorification?

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.”*

I started this blog as a continuation of a similar effort that I undertook (as a paid gig) for a large cable television network. I spent some time contemplating a suitable name for this undertaking, settling on The Veteran’s Collection for a number or reasons. The simplest of those reasons was to express my interest in militaria and how my status as a veteran guide both my interests and desire to preserve history.

Though my wife might argue, my collection of patches is rather small as compared to those of true military patch collectors. I tend to be more specific about the patches I seek (such as this USS Tacoma crest edition).

Often, I equate my collecting of military items in the vein of being a curator of military history and the role that the military has played in the securing and preserving of basic freedom for our nation (and for the people of other nations who have been trying to survive under repressive regimes). In gathering and collecting these items, it may appear to some that I am glorifying war. Having in my possession weapons (firearms, edged weapons, munitions, etc.) might signify glorification to the untrained eye however these items are part of the overall story being conveyed by collection.

As I scour my collection, I begin to realize that the overwhelming majority of items are Navy-centric. This 1950s U.S, Army cap is part of the display that I am assembling of my paternal grandfather’s older brother’s service.

I am a fairly soft-spoken person when I am out in public (though people who truly know me would have a difficult time believing this). When political conversations emerge near me (when waiting in line or casually walking past strangers in public settings) I have heard, on many occasions, discussions focus on perceptions of men and women who serve ( low-key or have served) in the armed forces. Often times, gross mis-characterizations regarding people in uniform begin to emerge as the dialog devolves into denigration of active duty and veterans as being war-hungry criminals, bent on killing innocents (women and children). I can’t count how many times I have stood in line, listening to people in front of me expressing how frustrated they are when they see a soldier in uniform ahead of them receiving a discount for a food item or service equating their time in service as legalized murder.

I served ten years on active duty and had two deployments into a combat theater, one of which I and my comrades were engaged by the enemy. In all of those ten years, I cannot recall a single person whom I served with who desired or wished to see combat. We prepared and trained for it hoping to never see it. I don’t think that I have ever met a combat veteran who wanted to talk openly about their time under fire. To have the uneducated civilian boil down our willingness to don the uniform, train for years while understanding fully that at some point during our service, we could see the horrors of combat as being blood-thirsty war-mongers only serves to show the extent of their ignorance.

I recently read two articles today concerning veterans of World War II who have (or had) committed their remaining years educating people about the horrors of war that each of them faced.

The first article was about one man, an IJN fighter ace Kaname Harada, who took every moment that he had left in order to do what the Japanese government is failing to do; educating younger generations to warn them about being drawn into future wars. “Nothing is as terrifying as war,” he would state to an audience as he spoke about his air battles from Pearl Harbor to Midway and Guadalcanal. As I read the article, I zeroed in on a chilling quote by one of Harada’s pupils, Takashi Katsuyama, “I am 54, and I have never heard what happened in the war.” He cited not being taught about WWII in school, continuing, “Japan needs to hear these real-life experiences now more than ever.” I am baffled that a man who is a few years older than me was not taught about The War in school.

In the second article, Army Air force fighter pilot, Captain Jerry Yellin, who like Harada, is educating young people about what he sees as futility of war. He is concerned that young Americans do not have an understanding of the realities of war nor what it is like to fight. “We’re an angry nation,” said Yellin. “We’re a divided nation: Culturally, monetarily, racially and religious-wise we’re divided.” What the veteran of 19 P-51 missions over Japan said (in another article) regarding war is often lost on those who are pacifists (at any and all costs) and lack understanding, “War is an atrocity. Evil has to be wiped out.” He continued, “There was a purity of purpose, which was to eliminate evil. We did that. All of us. So, the highlight of my life was serving my country, in time of war.”

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana

Both of these men clearly understand the cost of war and the hell that they faced when they took up arms and yet neither of them could be characterized with the ridiculous “war mongers” moniker often applied to warriors.

The reasons that people collect militaria are as diverse as each of the hobbyists’ backgrounds. The community of collectors can be completely aligned and in lock-step with each other on some militaria discussion topics and in near animus opposition on others. I tend to stay away from collecting medals and decorations; specifically, anything awarded to a veteran (or, posthumously to his family) due to how a great number of collectors commoditize certain medals (Purple Heart Medals, specifically). I withhold judgment as I abstain from even discussing the medals in question. For the laymen, a Purple Heart is awarded to service members wounded or killed in action. Collectors attach increased value for medals awarded (engraved with the recipient’s name) for posthumous medals; if the person is notable or was killed in a famous or infamous engagement, the value compounds (there are several other contributing factors that influence perceived monetary value).

- This is the Western Union telegram that was delivered to PFC Skavinsky’s wife, notifying her of his death. It took 10 days to get word to her. (Source: PurpleHearts.net)

- The Purple Heart Medal (photo source: PurpleHearts.net)

- The back of Skavinsky’s Purple Heart shows the official engraving of his name (Source: PurpleHearts.net)

- PFC Skavinsky’s accompanying certificate documenting the awarding of the medal and the date in which he was wounded. (Source: PurpleHearts.net

Purple Heart Medals are a very sensitive area of military collecting and nearly every medal was awarded to combat veterans – soldiers, marines, sailors and airmen who were serving in a war or wartime capacity. There are several collectors who use their Purple Heart collections to demonstrate the realities of the personal cost of war. These caretakers of individual history, such as this collector, painstakingly preserve as much of the information surrounding the WIA and KIA veterans, often maintaining award certificates and even the Western Union telegrams that were presented to the recipients’ parents or widows. Seeing a group with the documentation together is heart-wrenching.

A few of the selected items that my uncle brought back at the end of the war in Europe.

Militaria collecting can be very personal as many of the items, like medals (such as the Purple Heart) actually belonged to a person who served. In my collection, I have uniforms from men who served from as far back as the early 1900s up to and including the Vietnam War (not including my own as seen in this previous post) with the majority centered on World War II. Nothing could be more personal than the uniform worn by the veteran. Having personal items, in my opinion, enhances the collecting experience because of the desire to research what that service member did when they served. Uncovering a person’s story is to understand the sacrifice and cost of leaving family behind to serve rather than glorifying war itself.

Also in my collection are artifacts that were brought back by the veterans from the theater in which they served. While to some people, viewing these items may conjure negative and visceral responses, they still serve to tell a story that shouldn’t be forgotten. One of my relatives returned from German having recovered a great many pieces from the Third Reich machine after it was defeated by May of 1945. Still, this is not celebrating war nor the defeat of a (now former) foe.

There are other facets of my collection that are touch on the functions of engagement and combat; specifically armament and weapons. I have a few pieces that I inherited that, at some point, I will be delving deeper (on this blog) as they do fascinate me. I need to spend some time expanding my knowledge a bit more in order to present these pieces with a modicum of understanding (alright, I’ll admit that I don’t’ want to sound uneducated on my blog). Frankly, weapons are not my forte’ but what I own (a small gathering of edged weapons and ordinance), I have spent some time learning about them.

- I have a smattering of edged weapons (or, in this case, an edged tool) that I mostly inherited. This bolo knife was carried by Navy Pharmacists Mates (a.k.a “corpsmen”) who were attached to USMC units. The “U.S.M.C” embossed on the blade represents the United States Medical Corps.

- M1917 U.S. Military bolo knife and scabbard.

- 1942 M1 Garand Bayonet

Preserving history is paramount to helping following generations to both understand the cost of war and that, while doing what is necessary to avoid future wars, serves to illustrate that nations not only should but must take a stand against tyranny and evil.

See also:

* Military Memoirs of a Confederate, 1907, Edward Porter Alexander