Category Archives: Rates and Ranks

Cryptology and the Battle of Midway – Emergence of a New Weapon of Warfare

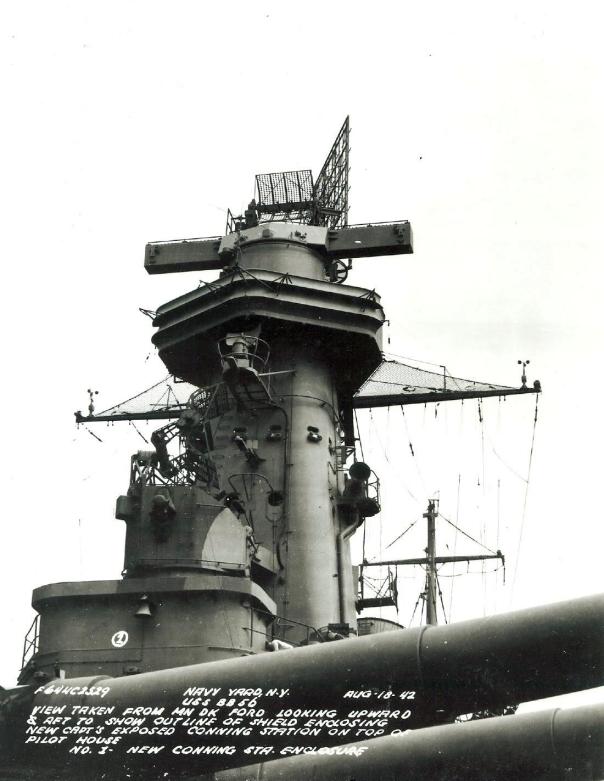

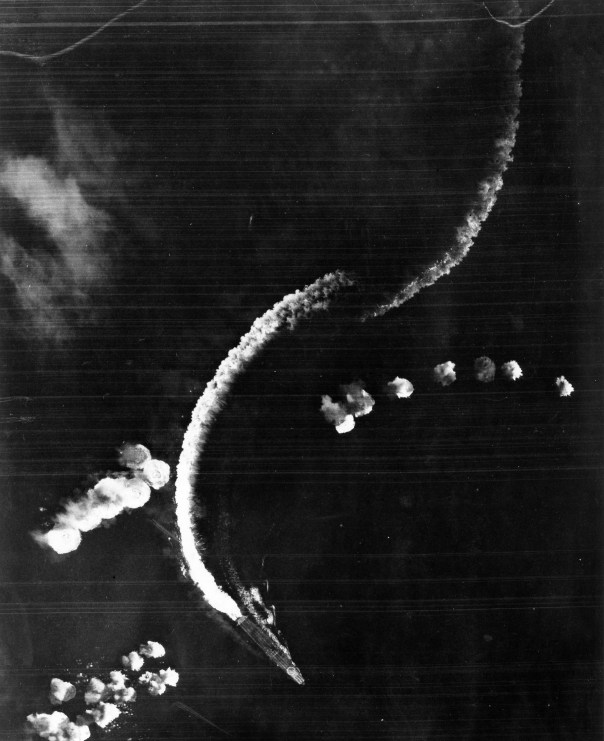

Here the Japanese carrier Hiryu dodges bombs dropped from Midway-based B-17 bombers (source: U.S. Navy).

The outcome of the war hung in the balance. Until now, the United States Navy’s operational effectiveness and readiness was in peril as they had suffered significant losses of the scant few carriers they had in the Pacific Fleet prior to December 7, 1941. The Imperial Japanese naval forces had extended their effective reach to include most of the Western and Southern Pacific and were seeking overall dominance of the ocean. The only opponent standing in their way was the severely weakened U.S. Navy.

In the previous six months, the American Navy had sustained strategic losses near Java with the sinking of the USS Houston (CA-30) in the Sunda Strait and the USS Edsall (DD-219) in the Java Sea, both on March 1.

Looking to put the Japanese on the defensive, American forces struck the Japanese homeland launching a (psychologically) successful air strike from the deck of the USS Hornet, causing Japanese military leadership to start holding back naval and aviation resources as a home guard, reducing the offensive capabilities. Japan had to consider herself vulnerable for the first time in the war while trying to convince citizens otherwise.

Continuing to press their imperial expansion Southward (Australia’s natural resources the ultimate goal), the Japanese, preparing for an offensive to take Port Moresby, New Guinea, began mobilizing the Combined Fleet in the South Pacific. American Forces countered and pressed for an attack which resulted in what came to be known as the Battle of the Coral Sea. While this battle was a strategic win for the United States, it was substantially painful losing the carrier Lexington and sustaining substantial damage to the Yorktown, leaving the Navy with just two serviceable flat tops, Enterprise and Hornet.

The Coral Sea battle demonstrated that over-the-horizon naval warfare had emerged as the new tactic of fighting on the high seas, as the carrier and carrier-based aircraft surpassed the battleship as the premier naval weapon.

While the Navy was very public in developing aviation during the 1920s, behind the scenes, a new, invisible weapon was being explored. Radio communication was in its infancy following World War I and adversarial forces were just beginning to understand the capabilities of sending instantaneous messages over long distances. Simultaneously, opponents were learning how to intercept, decipher and counter these messages giving rise to encryption and cryptology.

Officially launched in July of 1922, Office of Chief Of Naval Operations, 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section, Communications Security (or simply, OP-20-G) was formed for the mission of intercepting, decrypting and analyzing naval communications from the navies of (what would become) the Axis powers: Japan, Germany and Italy. By 1928, the Navy had formalized a training program that would provide instruction in reading Japanese Morse code communications transmitted in Kana (Japanese script) at the Navy Department building in Washington D.C. in Room 2646, located on the top floor. The nearly 150 officers and enlisted men who completed the program would come to be known as the “On The Roof Gang” (OTRG).

By 1942, Naval Cryptology was beginning to emerge as a viable tool in discerning the Japanese intentions. The Navy was beginning to leverage the intelligence gathered by the now seasoned cryptanalysts which ultimately was used to halt the Japanese Port Moresby offensive and the ensuing Coral Sea battle. However, the Japanese changed their JN-25 codes leaving the naval intelligence staff at Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (known as Station HYPO), headed by LCDR Joe Rochefort, scrambling to analyze the continuously increasing Japanese radio traffic.

A breakthrough in deciphering the communication came after analysts, having seen considerable traffic regarding objective “AF,” suggested that the Japanese were targeting the navy base at the Midway Atoll, 1,300 miles Northwest of Hawaii. While this information would eventually prove to be

invaluable and was ultimately responsible for placing Pacific Fleet assets in position to deal a crushing blow to the Japanese Navy, it was anything but an absolute, hardened fact. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz risked the balance of his carriers (Hornet, Enterprise and Yorktown) sending them to lie in wait of the assumed impending attack.

The attack came and the prepared American forces struck back, inflicting heavy damage to IJN forces, sinking four carriers, one cruiser and eliminating 250 aircraft along with experienced aviators. Though the war would be waged for another three years, the Japanese were never again on the offensive and would be continuously retracting forces toward their homeland. The tide had been turned.

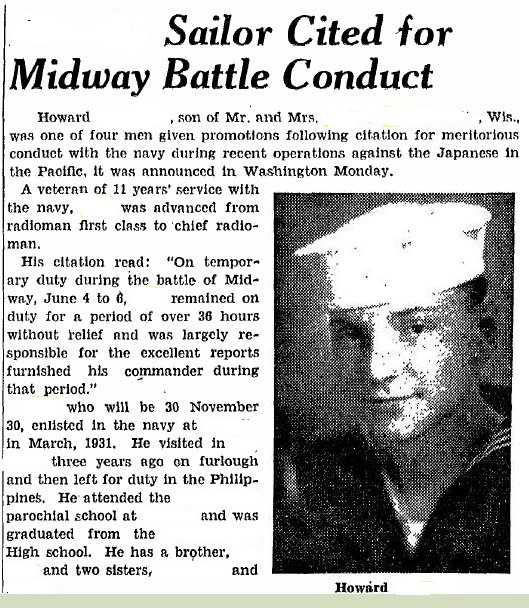

News clipping citing my uncle’s meritorious promotion (one of four sailors advanced for actions during the Midway battle) by Admiral Spruance .

On this 74th anniversary of the Battle of Midway, I wanted to spotlight a different aspect of the history of the battle, the emergence of cryptology as a strategic weapon, and share some of my own collection of that focuses on one of the original OTRG alumni, my uncle Howard.

Howard enlisted as an Apprentice Seaman in the Navy in 1932 (despite what the news clipping states) and proceed to serve in the fleet while working toward a radioman rating. He would be rated as a radioman 3/c in 1934 and accept an assignment to cryptological training at OP-20-G. In the years leading up to the war, he was assigned to Station HYPO and Station CAST (at the Cavite Navy Yard, Philippine Islands) transferring days before the Japanese raid.

- This service record entry shows that my uncle was meritoriously promoted for his actions during the Midway battle.

- This service record entry was also the text of my uncle’s commendation from Admiral Fletcher (acting CTF-16) for providing continuous intel.

Assigned to Station HYPO in early 1942, he would work closely with Commander Rochefort in code-breaking efforts and is purported (in my family circle) to have sent the transmission to Midway personnel to send un-coded messages about their inoperable evaporators, which ultimately led to the confirmation of Midway as Objective “AF.” He would be assigned to the Admiral’s staff (Admiral Raymond Spruance, who was substituting for Halsey at the time) aboard the Enterprise and would receive a meritorious promotion from the admiral as the result of his round-the-clock duties for the duration of the 4-day battle.

- Though these jackets never belonged to my uncle, they represent his achievement – reward for his dedication to duty during the most pivotal naval battle of WWII.

- Assembled from serviceable components from a few WWII navy hats, my dress blue chief radioman display is closer to being complete with this cover.

By 1944, my uncle had been promoted to the officer ranks, making Chief Radio Electrician, warrant officer-1. A career spent in naval cryptology, my uncle retired after 30 years of service.

Regretfully, none of my uncle’s uniforms, decorations or medals survives to this day. Neither of his sons inherited anything from their father’s more than 30 years of naval service. In my decision to honor him, I requested a copy of Uncle Howard’s service record (as thick as an encyclopedia) and began to piece his military tenure together by gathering uniforms and other associated elements. My collection of assembled uniform items representing his career, while not yet complete, has been a long endeavor – dare I say, a labor of love?

Military Records Research: Pay Attention to the Details

Genealogical research is funny. Overlooking the smallest, insignificant details can insert unintended road blocks into continuing down a valid pathway. With my family (which, I suppose isn’t too different from most families), there are so many branches of the tree to pursue which demands a lot of time spent down in the details. One little detail that I overlooked, kept me guessing on and off for over a year.

In July of 2012, I requested and obtained the WWI Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF) service records for my maternal grandmother’s father after making an Ancestry.com discovery of his military attestation record (his service was unknown to my family). Having served in the U.S. military, I am rather familiar with acronyms and terminology that is prevalent across multiple branches of the armed forces. In reviewing my great-grandfather’s CEF records, I began to realize that a fair amount of the documentation was difficult to discern, so much so that I found myself focusing more on the terms I did know and overlooking those that I was unfamiliar with.

Unfamiliar with the any of the Canadian military information, “Special Case” was very nebulous. Without an understanding of the references listed here, I was left guessing as to what this meant.

In examining the rather thin record, I found that my great-grandfather had been called up and was inducted on April 22, 1918 and was discharged on May 6, 1918 after just 15 days of service in the Canadian Army. The discharge certificate reads: “Discharge from the service by reason of ‘Special Case’ Authority Routine Order No. 180 dated 3-2-13. D.C.C. 11 M.D. 99-4-113-13.” This reason was found on several of the pages of his out-processing so from there, I made assumptions and ignored some of the other, more detailed data. I figured that he might have had a medical condition (note the “M.D.” in the above typed reason) or, perhaps there was a family hardship. Either way, he served slightly more than two weeks prior to being discharged.

The question: If he was drafted into the Army (CEF), then why is he wearing a maritime uniform?

A few years ago, my mother presented me with a box full of snapshots and photographs to scan (which I am slowly working on…when I have the time) in an effort to make them available to whoever in the family desires. One of the pictures caught my attention about the time I received my grandfather’s CEF records. The photo was a framed enlargement (from a snapshot) that showed my great-grandfather in a maritime uniform that was clearly Canadian (or British, even). My exposure to anything Canadian maritime was limited to lifting a few cans of Molson aboard a Canadian Destroyer in Pearl Harbor and riding the British Columbia Ferries to Vancouver Island. Translation: I know next-to-nil about Canadian uniforms (military or civil). Looking at my great-grandfather, I was left guessing.

The perplexing part of this story was that the uniform was maritime rather than Army (the CEF Army uniforms were very similar to the American Expeditionary Forces Army uniforms). Needless to say, I was entirely in the dark. Why was a two-week army veteran wearing a clearly non-army uniform? Since last year, the photo has been displayed on a table in our living room inspiring questions from family and guests as to the subject and the uniform in question.

In researching another relative who served in the CEF, I finally decided to reach out to experts to see if someone could enlighten me as my uninformed searches over the last year yielded zero positive results. On Tuesday of this week, I posted the images to a Canadian militaria collector’s forum and sent them to the Canadian Navy League. Today, I received word that the uniform is that of a Canadian naval petty officer first or second class. Thankful for the confirmation, I was still left guessing as to why my ancestor was wearing a navy uniform when he served in the army.

The cause of discharge as listed on this page that was deeper into the records documents was entirely overlooked. “To join R.N.C.V.R. was left hidden until today.

I scanned the Canadian Archives site to determine the next approach to see if I would be able to request records of my great-grandfather’s naval service (if they actually exist). None of the information stood out to me so I decided to take another peek at the CEF records that I already had. As I skimmed through each page, I kept seeing the same reference to the reason for discharge. A few pages deeper, something leapt off the page: “Cause of Discharge – to join R.N.C.V.R.” One simple Google search and I had it nailed. My great grandfather left the Army to join the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve.

Armed with this information, I can now pursue (and hopefully be successful) my great grandfather’s naval reserve service records. Clearly he served long enough to advance to petty officer 2nd or 1st class in a short period of time. By October of 1922, my great grandfather and his bride emigrated to the United States and settled in what would become, my hometown. Less than ten years later, he would pass away leaving behind two young daughters and his widow. Any inkling of his wartime service was lost to the ages, leaving me to discover it more than 90 years later.