Category Archives: Headwear | Helmets

Collecting U.S. Navy Uniform Ship Identifiers

To suggest that veterans and sailors of the U.S. Navy have an affinity for their ships would be a gross understatement. It would be difficult to stroll through any public area without seeing a former navy man sporting a ball cap with a USS ___ (fill in the blank). I have seen men well into their late 80s proudly carrying the name of the ship they served aboard, emblazoned across their foreheads, and as I write this, I am proudly wearing one of my own ship’s ball caps.

This collection of uniforms shows four official shipboard navy ball caps, authorized for wear with utility uniforms (such as the now-defunct dungaree set on the right). Note the UIM patch on the right sleeve of the dress blue uniform jumper.

Navy ship ball caps are quite commonplace. Many of them have icons or symbols between the name and the hull number designator that make them unique to each specific ship. Some of the symbology might have nothing to do with the ship, instead being representative of the commanding officer or the crew. As far as I’ve determined, ships’ crews have been wearing the named caps aboard ship with utility (dungarees) since the 1960s.

The two blue UIM patches shown are authorized by Navy uniform regulations. The white patch on top is a manufacturing mistake and unauthorized for wear on a Navy uniform. The USS Camden was decommissioned in 2005.

When sailors are required to be in their dress uniforms, identifying them with their associated commands is a requirement… especially when sailors behave like, well… sailors in foreign ports. Present-day enlisted dress uniforms must be adorned with a unit identification mark (UIM) patch on the top of the shoulder of the right sleeve. This regulation has been in place since the late 1950s to early 1960s.

Prior to World War II, the navy employed a much more stylish format of placing the command names on their enlisted sailors. From the 1830s to 1960, sailors wore with their dress blue uniforms a flat hat, affectionately known as the “Donald Duck” hat. Though it wasn’t authorized, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, sailors began to adorn their flat hats with a ribbon (known as a tally) that displayed the name of the ship and was worn only when on liberty (“shore leave” to you landlubbers). Eventually, the tallies were acknowledged within the naval uniform regulations, standardizing their appearance and wear.

This post-1941 Navy flat hat shows the generic “U.S. Navy” tally. By 1960, these hats were retired from use.

By 1941 and the outbreak of World War II, the rapid expansion of the fleets with many new ships under construction and being delivered to the fleet, the Navy did away with the ship names on the tallies, standardizing all with “U.S. Navy” (there is some speculation that secrecy of ship movement drove the Navy to implement this change).

Ship-named tallies are highly sought after by collectors, pushing prices on some of the more famous (or infamous) vessels well into the ranges of multiple-hundreds of dollars, regardless of condition. Due to the delicate nature of the tallies’ materials and the exposure to the harsh marine environment, the gold threads of the lettering tend to darken and tarnish. The ribbon construction was typically made with silk, so they don’t stand up well to the ravages of several decades of time and storage.

In the last few years, a tally showed up in an online auction for the first time in more than a decade of staking out anything related to USS Vincennes. Until then, I had my doubts as to whether the Navy had allowed the pre-war crew to have the tallies for their ship, even though it was in service since February of 1937, four years before they were abolished. Sadly, the selling price surpassed my maximum bid by nearly triple the amount.

This image shows the rare USS Vincennes tally (along with some officer cap devices), which was sold this week at auction for more than $150 (source: eBay image).

Hopefully, I don’t have to wait as long until I see another USS Vincennes tally!

Cryptology and the Battle of Midway – Emergence of a New Weapon of Warfare

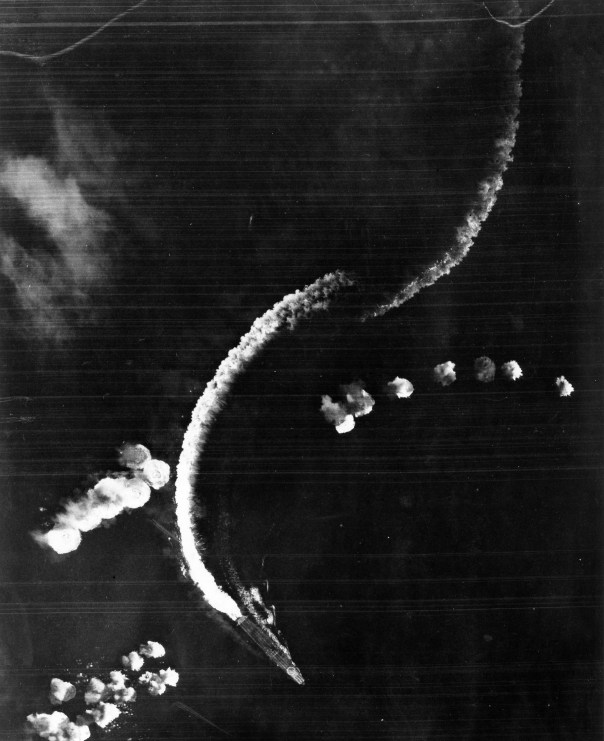

Here the Japanese carrier Hiryu dodges bombs dropped from Midway-based B-17 bombers (source: U.S. Navy).

The outcome of the war hung in the balance. Until now, the United States Navy’s operational effectiveness and readiness was in peril as they had suffered significant losses of the scant few carriers they had in the Pacific Fleet prior to December 7, 1941. The Imperial Japanese naval forces had extended their effective reach to include most of the Western and Southern Pacific and were seeking overall dominance of the ocean. The only opponent standing in their way was the severely weakened U.S. Navy.

In the previous six months, the American Navy had sustained strategic losses near Java with the sinking of the USS Houston (CA-30) in the Sunda Strait and the USS Edsall (DD-219) in the Java Sea, both on March 1.

Looking to put the Japanese on the defensive, American forces struck the Japanese homeland launching a (psychologically) successful air strike from the deck of the USS Hornet, causing Japanese military leadership to start holding back naval and aviation resources as a home guard, reducing the offensive capabilities. Japan had to consider herself vulnerable for the first time in the war while trying to convince citizens otherwise.

Continuing to press their imperial expansion Southward (Australia’s natural resources the ultimate goal), the Japanese, preparing for an offensive to take Port Moresby, New Guinea, began mobilizing the Combined Fleet in the South Pacific. American Forces countered and pressed for an attack which resulted in what came to be known as the Battle of the Coral Sea. While this battle was a strategic win for the United States, it was substantially painful losing the carrier Lexington and sustaining substantial damage to the Yorktown, leaving the Navy with just two serviceable flat tops, Enterprise and Hornet.

The Coral Sea battle demonstrated that over-the-horizon naval warfare had emerged as the new tactic of fighting on the high seas, as the carrier and carrier-based aircraft surpassed the battleship as the premier naval weapon.

While the Navy was very public in developing aviation during the 1920s, behind the scenes, a new, invisible weapon was being explored. Radio communication was in its infancy following World War I and adversarial forces were just beginning to understand the capabilities of sending instantaneous messages over long distances. Simultaneously, opponents were learning how to intercept, decipher and counter these messages giving rise to encryption and cryptology.

Officially launched in July of 1922, Office of Chief Of Naval Operations, 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section, Communications Security (or simply, OP-20-G) was formed for the mission of intercepting, decrypting and analyzing naval communications from the navies of (what would become) the Axis powers: Japan, Germany and Italy. By 1928, the Navy had formalized a training program that would provide instruction in reading Japanese Morse code communications transmitted in Kana (Japanese script) at the Navy Department building in Washington D.C. in Room 2646, located on the top floor. The nearly 150 officers and enlisted men who completed the program would come to be known as the “On The Roof Gang” (OTRG).

By 1942, Naval Cryptology was beginning to emerge as a viable tool in discerning the Japanese intentions. The Navy was beginning to leverage the intelligence gathered by the now seasoned cryptanalysts which ultimately was used to halt the Japanese Port Moresby offensive and the ensuing Coral Sea battle. However, the Japanese changed their JN-25 codes leaving the naval intelligence staff at Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (known as Station HYPO), headed by LCDR Joe Rochefort, scrambling to analyze the continuously increasing Japanese radio traffic.

A breakthrough in deciphering the communication came after analysts, having seen considerable traffic regarding objective “AF,” suggested that the Japanese were targeting the navy base at the Midway Atoll, 1,300 miles Northwest of Hawaii. While this information would eventually prove to be

invaluable and was ultimately responsible for placing Pacific Fleet assets in position to deal a crushing blow to the Japanese Navy, it was anything but an absolute, hardened fact. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz risked the balance of his carriers (Hornet, Enterprise and Yorktown) sending them to lie in wait of the assumed impending attack.

The attack came and the prepared American forces struck back, inflicting heavy damage to IJN forces, sinking four carriers, one cruiser and eliminating 250 aircraft along with experienced aviators. Though the war would be waged for another three years, the Japanese were never again on the offensive and would be continuously retracting forces toward their homeland. The tide had been turned.

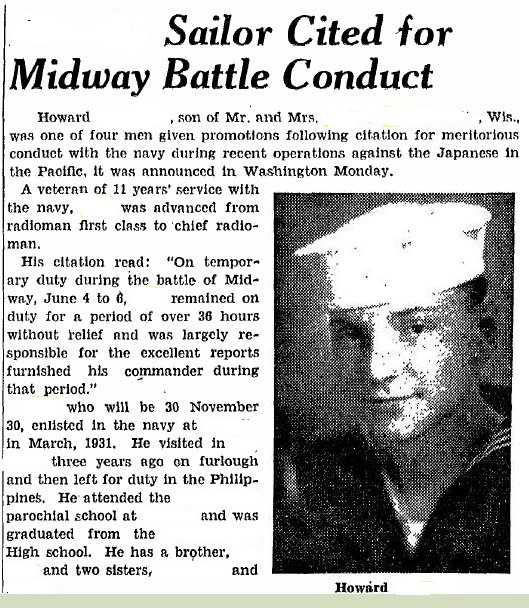

News clipping citing my uncle’s meritorious promotion (one of four sailors advanced for actions during the Midway battle) by Admiral Spruance .

On this 74th anniversary of the Battle of Midway, I wanted to spotlight a different aspect of the history of the battle, the emergence of cryptology as a strategic weapon, and share some of my own collection of that focuses on one of the original OTRG alumni, my uncle Howard.

Howard enlisted as an Apprentice Seaman in the Navy in 1932 (despite what the news clipping states) and proceed to serve in the fleet while working toward a radioman rating. He would be rated as a radioman 3/c in 1934 and accept an assignment to cryptological training at OP-20-G. In the years leading up to the war, he was assigned to Station HYPO and Station CAST (at the Cavite Navy Yard, Philippine Islands) transferring days before the Japanese raid.

- This service record entry shows that my uncle was meritoriously promoted for his actions during the Midway battle.

- This service record entry was also the text of my uncle’s commendation from Admiral Fletcher (acting CTF-16) for providing continuous intel.

Assigned to Station HYPO in early 1942, he would work closely with Commander Rochefort in code-breaking efforts and is purported (in my family circle) to have sent the transmission to Midway personnel to send un-coded messages about their inoperable evaporators, which ultimately led to the confirmation of Midway as Objective “AF.” He would be assigned to the Admiral’s staff (Admiral Raymond Spruance, who was substituting for Halsey at the time) aboard the Enterprise and would receive a meritorious promotion from the admiral as the result of his round-the-clock duties for the duration of the 4-day battle.

- Though these jackets never belonged to my uncle, they represent his achievement – reward for his dedication to duty during the most pivotal naval battle of WWII.

- Assembled from serviceable components from a few WWII navy hats, my dress blue chief radioman display is closer to being complete with this cover.

By 1944, my uncle had been promoted to the officer ranks, making Chief Radio Electrician, warrant officer-1. A career spent in naval cryptology, my uncle retired after 30 years of service.

Regretfully, none of my uncle’s uniforms, decorations or medals survives to this day. Neither of his sons inherited anything from their father’s more than 30 years of naval service. In my decision to honor him, I requested a copy of Uncle Howard’s service record (as thick as an encyclopedia) and began to piece his military tenure together by gathering uniforms and other associated elements. My collection of assembled uniform items representing his career, while not yet complete, has been a long endeavor – dare I say, a labor of love?

The Militaria Collector’s Search for the White Whale

The hunt. The search. The quest for the prize. Seeking and finding the “Holy Grail.” We collectors tend to describe the pursuit of those elusive pieces that would fill a glaring void in our collection with some rather lofty terms or phrases.

We wear our collection objectives on our sleeves while pouring through every online auction listing, or burning through countless gallons of gasoline while making the rounds from one garage or yard sale to the next. Antiques store owners (whom we think are our friends) have our lists of objectives to be on the lookout for.

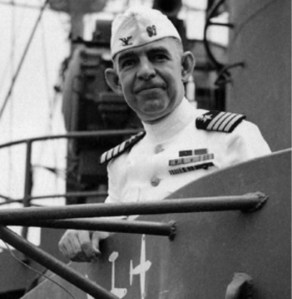

A close-up of the USS Astoria’s first commanding officer, Captain George C. Dyer, wearing his choker whites and the rare white garrison cover (source: Brent Jones Collection).

Militaria collectors (any collector, for that matter) thrive on the hunt and feed off the adrenaline rush that comes from achieving each victory as they locate and secure the piece that has seemingly evaded every search effort. Hearing that they’ve missed an opportunity by seconds due to some other collector beating them out only fuels their passion. Losing an auction because they tried to play conservatively with their bidding propels them through the twists, turns, hills and valleys of the emotional roller coaster.

Searching for militaria can be an exhausting endeavor. For the last two years, I’ve been searching for a piece and while I can’t say that I’ve been through these scenarios, I did manage to feel an amount of elation when I achieved success with my objective.

This shot shows Captain George C. Dyer departing the Astoria wearing his dress white uniform and the white garrison cover (source: Brent Jones Collection).

I’m not wanting to repeat myself (which I do quite often, considering all of my previous posts), but let me state that I do not consider myself any manner of expert on military history or militaria. I assert that I have a broad-based knowledge on a narrow scope of U.S. military history (20th century) with a primary focus on the U.S. Navy. So when I discovered an item that I had previously never knew existed, I was quite curious and subsequently needed to obtain it.

An acquaintance (who had contributed photos for my first book that I published in 2009) has a website that is the public face of his extensive and invaluable research on the USS Astoria naval warships. On this site, I noticed some new images that he had recently obtained and published showing the first commanding officer, Captain George C. Dyer, of the USS Astoria CL-90 turning over command of the ship and departing amidst his change of command ceremony.

Pictured here with an early WWII chief radioman’s eight-button, dress white uniform jacket, the (yellowing and aged) white garrison cover is a bit more distinguishable from a khaki variant.

For the ceremony, the ship’s crew is turned out in their summer white dress uniforms. All appeared to be normal until I spied the unusual uniform item – the commanding officer was wearing a garrison cover (hats in the Navy or Marine Corps are known as covers). Affectionately known as a (excuse the crass term) “piss cutter,” I knew that the garrison was available for use with the (aviator) green, khaki, (the short-lived) gray and the blue uniforms, but I had never seen a photo of this white variety. Garrison covers are not particularly stylish, but due to their lightweight and soft construction, they are considerably more comfortable than the traditional combination cover (visor caps) alternatives.

A Garrison Comparison: at the top is the white garrison (compared with a WWII khaki) demonstrating that, though it is yellowed, it is the rare white cap.

Plentiful and very readily available, the khaki versions are quite frequently listed or for sale at antiques stores and garage sales. The green, gray and blue garrisons are a little bit more rare yet turn up with some regularity. The white garrison is the great, white whale. Considering that it was not well-liked in the fleet during the war (when it was issued), it is now extremely rare for collectors seeking to possess all of the uniform options. The white garrison is truly the white whale among World War II navy uniform items.

Seeing this hat in the photos fueled my quest to obtain one for my collection. The very first one I had ever seen listed anywhere became available last week at auction. I placed my bid at the very last second and was awarded with the holy grail. Yesterday, the package arrived and was both elated and saddened as my quest was fulfilled.

No longer needing to hunt for this cover, I feel as though I have lost my way… a ship underway without steerage. What am I saying? I have plenty of collecting goals un-achieved!

Naval Coverings of WWII – Navy Hats

My military collecting focuses almost entirely on documenting my family’s service with both a narrative and visual materials. One of the products of my research will ultimately be a hardbound, four-color book complete with original photographs of these veterans and displays of their uniforms and artifacts. You’ll have to take my word that this is a lengthy undertaking, considering that most of my subjects are long-deceased, requiring interaction with the National Archives and a lot of lag time waiting for the requested service records and materials.

As I began assembling a representative group portraying my uncle’s service in the United States Navy, I soon realized that I would have to collect several uniforms as he went from an Apprentice Seaman to a Chief Warrant Officer during his thirty years of service. For this article, I am going to cover one aspect of the assembled group : headwear.

My uncle enlisted in 1932 and remained on active duty throughout World War II. By 1941, he had advanced to first class petty officer radioman. His specialty was in intelligence and he had been with Joe Rochefort, having attended the Navy’s highly secretive and fledgling cryptologic school in the 1930s. He was meritoriously promoted to chief petty officer (CPO) for his efforts supporting the commander of Task Force 16 during the Battle of Midway. In 1944, he was promoted again to Radio Electrician, Warrant Officer (grade W-1).

Possessing that information, I knew that I had to collect some chief petty officer uniforms as well as some difficult to find warrant officer items. To complete those sets, headgear could pose a significant challenge. I first had to determine what a W-1 (the Navy discontinued this rank at the war’s end) would wear as I had personally never seen the uniform. I referred to some reference material that provided some basic information, but not the specifics regarding all of the hat components for this grade. I could select either (or both) a combination or garrison cap.

With a khaki jacket in my possession and the appropriate epaulettes (shoulder boards) that are affixed to the jacket’s shoulders, I knew that I wanted to have at the very minimum, a garrison cover. Current Chief Warrant Officers’ garrison cover devices include the naval officer’s crest on one side and the rank bar on the opposing side. The rank bar devices did not exist yet during the war (instituted in the 1950s) so I was at a loss for what they wore. I contacted some navy uniform experts who informed me that the W-1 would wear only their specialty devices (in this case, the radioman insignia). During WWII, these devices are mirrored, meaning that they both “point” forward yet look the same from either side. Current devices are not mirrored – Chief Radio Electricians wear two of the same device – one is upside down.

I located a vintage set of the devices and pinned them to the WWII-vintage Navy khaki garrison cap that I had previously obtained. The hat was now complete.

WWII-Era U.S. Navy Radio Electrician Warrant Officer’s Garrison Cap.

I turned my attention to the combination cover (some erroneously call the Navy caps “visor caps”) which is a hat with a visor that may be simply altered to match the uniform by replacing the cover with the appropriate color/material cover. Chiefs and officers could feasibly own a single hat frame (the sweatband/frame/visor) and simply change from white to blue or khaki (also grey or green) to align with the uniform of the day. I wanted to create a combination cap to go with this uniform as it looks classy.

I located a standard officer’s dress blue cover with the wide gold chin strap and the line officer’s crest. I already had a nice example of this cap so I decided that this would be a good base to create the warrant hat. Any alterations I made could easily be reversed to return it to its original state. I also kept the original owner’s name placard in the holder inside the hat. I found an original W-1 hat band and a 24k large hat insignia as well as the unique ½-inch gold chin strap (all vintage components). I disassembled the hat and replaced the appropriate parts with the newly acquired components.

WWII U.S. Navy Warrant Officer’s (W-1) Combination Cover

One last cover I focused on was the CPO hat. Examining numerous period-photographs, I locked onto the hat that I wanted to acquire or assemble. Through the assistance of a friend, I was directed to an early WWII CPO combination cap with a grey cover that was well-enjoyed by a family of moths. The sterling silver hat device was outstanding as was the remainder of the hat. I purchased the hat and obtained a set of covers (blue, white and khaki) to accompany the three CPO uniforms (all chief radioman). Now I could display each chief uniform with using a single combination cover.

World War II-Era U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer Combination Cover.

The remaining uniform left to tackle (for this relative, at least)? A dress blue or white jumper with neckerchief and white hat.