Blog Archives

Militaria Collecting Made Complicated – No Checklists

Posted by VetCollector

Prior to delving into militaria and historical research, I collected sports cards for years. My principal interest in this arena was with baseball which is also my favorite sport to watch. Back then, my interest in the game centered on the history – the “golden era” – and the legends of the game. However, with baseball card collecting, I chose to focus on the 1950s and 1960s.

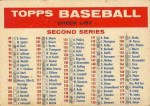

This 1957 Topps baseball card checklists shows the marks the collector made as they worked to complete the set.

With so many players in the game (not all of them represented on a card) in the early 1950s, card companies recognized that they could create more interest by letting their target audience know how many different cards were produced. This information, in the form of checklist cards, contained all the information that informed collectors what cards were produced. This information would keep collectors buying the wax packs (of course, getting the wonderfully powdered sugar covered, hard sticks of bubblegum) and trading their extras with their friends. As they filled out their sets, collectors would check their checklists.

Militaria couldn’t be a more polar opposite from sports card collecting. There are no checklists and finite production runs, no hardened rules about variations, no price guides that afford collectors with knowledge of sales trends….none of that. Militaria collecting requires the collector to acquire knowledge about the artifact – where it was used, who used it, when it was produced and available, when it was issued, how it was modified (in the field), etcetera – before they commit significant finances to collecting.

The right-sleeve rate of the 1905-1913 coxswain (with an additional chevron, this would be a boatswain’s mate 2nd class petty officer).

Navy rate collectors can tell stories about variations and just how frustrating it can be to acquire all of the renditions of a specific rate. When considering a long-standing rate, such as a boatswain’s mate (pronounced “bosun’s mate”, BM for short) that has been in existence since the founding of the U.S. Navy, its rate badges have gone through considerable transition. One could assemble an amazing volume of examples of each badge iteration as BM (and Coxswain) insignia have been around since the 1880s.

With each change to uniform regulations (1886, 1905, 1913, 1941, 1946, and so on) rate badges were impacted. Some changes were simply moving from one sleeve to the other (1946) while still others changed the design of the crow (the design of the eagle, color of the chevrons). Additional variations stem from the uniform that the crow is applied to (khaki, blues, whites, greens, grays) as well as the material variations of the base fabric (multiple iterations of blue and white cloth) or the color of the chevrons and eagle (such as bullion).

If a collector focused solely on the boatswain’s mate rate spanning its entire existence, the collection could potentially be quite large and very costly to build. Unfortunately, there are no checklists to guide collectors. What can confound collectors is the discovery of a rate variant that has never been seen before by seasoned, knowledgeable experts.

This Screaming Eagles patch is one of countless variants for collectors to pursue (source: Topkick Militaria).

Similar to rate collecting, U.S. Army patches are very diverse and have experienced many iterations over the course of their employment on uniforms. Variations exist within the same era on the same patch design which give collectors reason for pause as they try to collect every option available. Since I don’t really dabble in army patches, my eyes tend to glaze over when other collectors begin to espouse the many facets of the World War II-era Screaming Eagles shoulder insignia. From the different “airborne” tabs to the design of the eagle’s eye and tongue, the 101st Airborne patch could occupy collectors for years as they seek to assemble a complete collection. Cut-edge, marrowed-edge, fully embroidered, felt, greenbacks, white backs, the possibilities are seemingly endless making the concept of having a checklist ideal.

While I can’t vouch as to the authenticity of this being the real thing, it is the design of a World War II Rangers patch (source: SA Militaria).

One aspect I’ve not mentioned and won’t really delve into is the issue of fakes. When a television show or film achieves the level of popularity that Saving Private Ryan (SPR) and Band of Brothers (BoB) have, shady characters create opportunities to separate novices from their hard-earned cash. The Ranger (SPR) and Screaming Eagles patches (BoB) are some of the most heavily-faked embroidery in the militaria market.

In all fairness to those who invest heavily into these areas (with both time and finances), the main reason I shy away from army patches (specifically Rangers and 101st) is that I have no idea how to tell a fake from the real McCoy. I suppose that the pricing of some of the more rare variants (sometimes in excess of $1,000) keep me steering well-clear of collecting army patches all together.