I am an American Veteran with Canadian Military Heritage

I’ve been revisiting my family tree research, spurred on by catching up on watching episodes of The Learning Channel’s Who Do You Think You Are? (WDYTYA) The show follows a pretty simplistic theme of tracing some Hollywood notable’s ancestral history as they have been suddenly overcome with desire to know where they came from. There is always some sort of misplaced desire for self-validation as they seek to identify with the very real struggles that someone in their family tree endured centuries ago. In watching them I often find the humor as the celebrity emotionally aligns with a nine or ten times great grandparent as if that person were an active part of their life. Where the humor in this originates is that one must consider exactly how many great grandparents one has at this particular point in our ancestry.

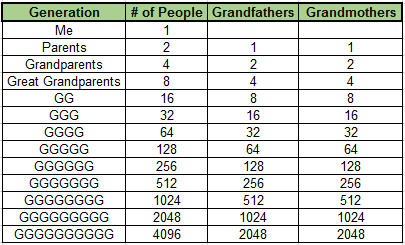

My 3x great grandfather (one of sixteen such 3x great grandfathers) served with the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry during the American Civil War) and like the Hollywood celebrities on WDYTYA, I have researched him extensively and I do identify with him. But consider that there are 15 other 3x great grandfathers along with eight 2x greats, four greats and two grandfathers. That means that five generations above me encompass 28 grandfathers including the lone Civil War veteran that I thoroughly researched. If viewed this prospective with another one of the great grandfathers (whom I researched and found to have served during the American Revolution), he would be one of 64 5x great grandfathers (for a total of 254 total grandfathers at this generation-level). This can get confusing to grasp without a visual:

When folks refer to their 7th great grandfather, what does that mean? Did they have more than one? The answer is that everyone has 256 7th great grandfathers. It is simple math, folks!

There are a few other pieces that I have for the display that I am assembling, including a section of vintage ribbon for the service medal. The shoulder tabs are a more recent acquisition as is the CFC hat badge (bottom left) that my 2x great grandfather wore prior to being assigned to the 230th. The two smaller insignia flanking the medal were worn on the uniform collar. The pin on the lower right was a veteran’s organization pin.

I have been gathering artifacts together to create representations of some of my ancestors with military service. I have been sporadically researching as many relatives as I can locate to document a historical narrative of service by members of my family. This is a daunting task considering how many direct ancestors I have and I have been also including some uncles and cousins as I uncover them. One of my 2x great grandfathers (one of 8 such great grandfathers) was a British citizen who emigrated to Victoria, British Columbia with his wife and ten children a few years following the turn of the twentieth century. By the time the Great War broke out in Europe in 1914, he was a 45-year-old carpenter and home builder. When he was drafted into the Forestry Corps of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in June of 1916, he was 47 and a widower. He served in Europe for the duration of the war harvesting timber for use in the war effort, plying his carpentry skills in some fashion being far too old for combat duty.

Having a Canadian veteran ancestor (one of two – I wrote about the other one, previously) posed some challenges in researching his service as nearly every aspect of research is different from what I am familiar with (with American military records). Learning the terminology and the unit structure was difficult but even more challenging was deciphering my GG grandfather’s service records let alone locating details as to what his uniform insignia and devices would have been. Thanks to a few helpful CEF sites and forums, I was able to piece together some of the principle elements in order to assemble a shadow box at some point in the future.

This is a simple, yet tasteful display of a veteran of the 230th Canadian Forestry Corps from WWI. This soldier was in the same unit as my 2x great grandfather.

As any Canadian militaria collector could tell you, locating pieces from individual regiments/units of the Forestry Corps can be daunting. When I started on this path a few years ago, the prices were higher than those of American units by as much as three times. Collar and cap devices and badges were can reach prices beyond $40-50 (collar) and $70-100 (for caps badges). Not that ever intended to purchase actual uniforms pieces (tunic, cap, hat, etc.), I still maintained a watchful eye just to see what might show up for sale. Today, my eyes were enlarged and mouth left agape when something appeared in my automated search for such items.

Listed yesterday on eBay was a 1917-dated British trench hat that is in impeccable condition, complete with the badge of my 2x great-grandfather’s unit. Everything about this century-old cap seems to be in an incredible state – the hat’s shape, the leather sweatband – all of it. But then I saw the opening bid amount – $750.00 (in USD) – and immediately, my jaw struck my desktop beneath me! In the “People who viewed this item also viewed” section were British head covers (one trench hat and two visor caps) of comparable condition but with devices from other, non-Forestry units with prices that ranged from $500-700, depending upon the unit insignia. The hat from my ancestor’s unit topped the range of prices. Being in possession of the cap device, I wouldn’t need to pursue such an expensive purchase (I don’t need the hat for the display that I am assembling) so I will simply watch to see if the hat does end up finding a new home and take note of the selling price.

- This hat differs from the peak cap in that the top is slouched down over the sides and the bill is soft and stitched like a baseball cap. The 230th Canadian Forestry Corps device is centered over the leather chinstrap (eBay image).

- Showing the hat’s right side and the top of the visor (eBay image).

- The close up of the CFC badge – the insignia incorporates crossed pikes superimposed over a maple leaf with a long crosscut saw with a beaver (eBay image).

- The chinstrap button detail is impressive (eBay image).

- The high-level view of the hat’s underside (eBay image).

- These markings appear to be the maker’s mark, the hat’s size and the date of manufacture (eBay image).

- I am unfamiliar with these markings. I am sure that the experienced collectors and historians could easily provide some insight as to their meaning (eBay image).

- On the sweatband, the soldier’s initials and service number are hand-inscribed and provide an easy path for researching the original owner’s service (eBay image).

With just one of my maternal 2x great grandfathers with military service (albeit, British-Canadian) and none of my paternal 2x great grandfathers, I don’t have any more military artifacts left to gather for this particular generation (unless I am able to discover new facts for others). The preceding and following generations reveal that I have a lot of research effort in store for me not to mention what lies ahead for me within my wife’s equally extensive family military history.

See Also:

Lumbering Along: Collecting C.E.F. Forestry Militaria

A Bullet with No Name

Most people who know me would agree with the statement that I take pleasure in the obscurity and oddities in life. If there is any sort military or historic significance, my interest is only fueled further.

Militaria collectors have heard the same story told countless times by baffled and befuddled surviving family members – the lost history of an object that (obviously) held such considerable personal significance that a veteran would be compelled to keep the item in their inventory for decades. For one of my veteran relatives, that same story has played out with an item that was in among the decorations, insignia and other personal militaria, preserved for fifty-plus years.

The crimp ring around the middle of the bullet’s length shows where the top of the bullet casing was pressed against the projectile. When compared to these WWII .45cal rounds, it becomes apparent that the bullet is in the 7mm bore size-range.

When I received the box of items, I quickly inventoried each ribbon, uniform button, hat device and accouterments that dated from his World War I service through the Korean War. The one item that caught me by surprise was a long, slender lead projectile with a mushed tip.

They are difficult to make out with the naked eye, but the markings are “A-T-S” and “L-V-C”. The character in the center doesn’t appear to be a character at all.

It was clear that this blackened item was a small arms projectile. Based on size comparison with 9mm and 7.62 rounds, it was more along the lines of the latter, but it was clearly not a modern AK/SKS (or other Soviet-derivative). Perhaps it was a 7mm or smaller round? Without any means to accurately measure the bullet, I cannot accurately determine the bore-size or caliber. I’ll have to leave that for another day.

Further examination of the object proved to me that it was bullet that had been fired and had struck its target, causing the tip to blunt. While I am not a ballistics expert, I have seen the markings that firing makes on a bullet. This round clearly has striations that lead me to believe that it has traveled the length of a rifled barrel. It also possesses a crimping imprint, almost at the halfway-point on the projectile.

So what does all this information mean? Why did my uncle hang on to it for all those years? Had this been a bullet that struck him on the battlefield? Had it been a near miss?

In this view, the mushed tip is easily seen, as are some of the striations.

My uncle passed away 20 years ago and the story surrounding the bullet sadly died with him. Since he bothered to keep it, so will I along with other pieces in a display that honors several of my family members’ service.

Showing Off Your Collection is Not Without Risk

For the most part, militaria collectors enjoy anonymity and prefer to keep their collections private, sharing them with a scant few trustworthy people. Those whose collections include ultra-rare pieces tend to avoid the public exposure for good reason.

As someone with a passion for history, specifically United States military history, I enjoy viewing the work of other collectors and soak up the details of each piece they are willing to share with me. It brings me absolute joy to hold an item that is tied to a notable person or a monumental event as I try to picture the setting from where the piece was used. I often wonder how many times the piece has changed hands over the course of its existence. Not wanting to pry or press the collectors, I seldom inquire as to how they came to own the piece.

Some of you may wonder why a collector might choose to keep his work out of the public eye.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this area of collecting is the very personal nature of a vast number of pieces – meaning that items such as medals or decorations might be engraved or inscribed with a veteran’s name. While this personalization benefits the collector in that they have a means to research the item when tracing its “lineage” back to the original owner, it can also be a detriment.

I have witnessed situations where a collector posted a named piece on the web only to be contacted by a person claiming to be the next of kin of the original owner, while telling a sad (and sometimes convincing) story of how the items were sold or taken without their knowledge. Or worse yet, the original owner, perhaps suffering from age-related mental issues, let the items go during a lapse in judgement, depriving the child the ability to preserve the items. Demands, sometimes accompanied by threats of legal action, are subsequently directed toward the collector in an effort to acquire the pieces. There is no rock-solid way for the collector to validate the claims.

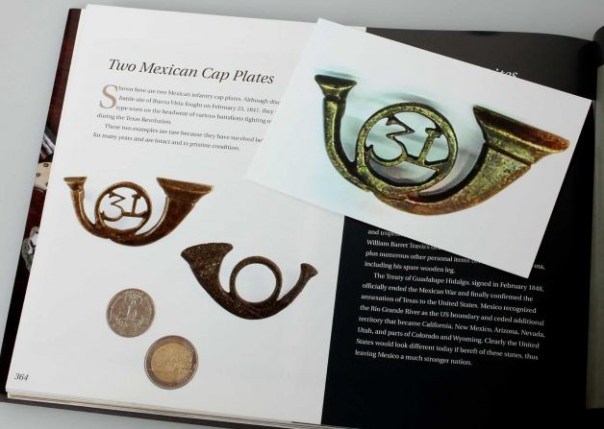

From Collins’ collection, this 1830 over and under flintlock pistol was excavated by at the Alamo site by a construction worker (source: Phil Collins collection).

In some instances, I have seen collectors happily repatriating militaria objects back to family members once the ownership claims have been substantiated. A few of those collectors, having made significant investments into acquiring the pieces, went as far as to gift the items to the family without seeking any sort of compensation.

As I turned on my computer today to check the news and catch up on emails, I noticed a developing story surrounding a prominent militaria collector whose collection I touched on a few weeks ago. It seems that a San Antonio man has filed a lawsuit against musician Phil Collins, seeking financial damages due to an alleged theft of Alamo relics from the trunk of the plaintiff’s vehicle. The suit names Collins as one of four defendants, who ultimately acquired the pieces from a San Antonio militaria dealer (also named as a defendant).

Related Stories:

- Musician at center of Alamo discord

- Local collector Don Ray Jank files lawsuit naming Phil Collins, others

- Phil Collins’ Alamo Book ‘Rock Solid,’ McMurry Professor Says

I won’t delve into the nature or details of the suit, but there is some history of the collector making accusations toward the dealer in the past, and this could be perceived as a personal conflict between the plaintiff and the dealer, but without having much knowledge of the case, I will not speculate as to who did what to whom as that is a matter for the courts to decide. What I do find fascinating is that the plaintiff is not seeking the return of his alleged “stolen” relics.

Though this cap plate is fairly common, the collector (who provided the comparison) shows a photo of his stolen plate as compared to one in Collins’ book, “The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey” (Photo by Juanito M. Garza, Courtesy Photo, Don Jank / San Antonio Express-News).

The Collins case underscores yet another pitfall of making one’s collection available for public review. Aside from opening the door for questions as to the authenticity of some of his pieces, this collector has exposed himself to challenges from anyone who might choose to make an ownership claim against him.

Combat Medical Blades – Bolo Knives

Indiana Jones faces off with a sword-wielding opponent on the streets of Cairo in Raiders of the Lost Ark (source: Paramount Home Entertainment (Firm). (2008). Raiders of the lost ark. Hollywood, Calif: Paramount Home Entertainment).

When confronted by a henchman in a scene from the film, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones (played by Harrison Ford) notices the fancy blade-wielding skills of his opponent. Unimpressed by the acrobatics and the fancy blade-twirling bad-guy, Indy retrieves his revolver from his holster firing a single, well-placed shot, dropping the adversary nonchalantly.

I don’t profess to have knowledge of the type of sword wielded by unimportant character in that film nor do I have expert knowledge in the field of military edged weaponry. What I do have in my scabbard is the ability to use the research tools at my disposal – which comes in quite handy when given an arsenal of knives, swords, bayonets and bolo knives.

A few years ago, I was asked to catalog and obtain value estimates of some militaria pieces that were part of a family member’s collection. He had passed away some time before and his executor was carrying out the responsibilities of handling the estate. In the previous years, I had only seen a few items from the collection so I was surprised when I saw what was there for me to review. After completing my work on behalf of the state, I later learned that I was to receive some of the pieces that I had appraised, much to my surprise.

Of the blades I had inherited, three were quite unique, different from the rest of the pieces. Two of the three blades were almost identical in form and the other was a slight departure from the others. What set these blades apart from the rest was machete-like design with more size toward the end of the blade, giving the blade a bit of weight toward the end of the blade rather than at the center or toward the hilt. The design of these blades were fashioned after the weapon of choice of the Filipino resistance fighters from the revolt that started at the end of the Spanish-American war in 1898.

Known simply as bolo knives, the U.S. military-issue blades were less weapon and more utilitarian in function.

- The unique brass belt hanger of the leather-clad scabbard is much different from most WWI web gear attachments.

- The M1904 hospital corps bolo with its unique s-shaped brass hilt.

Now in my collection, the oldest of the three knives is the M1904 Hospital Corps Knife. Though many people suspect that the broad and heavy blade was important to facilitate field amputations, this thought is merely lore. Along with the knife is a bulky, leather-clad scabbard with a heavy brass swiveling brass belt hanger. My particular example is stamped with the date, “1914” which is much later in the production run. The M1904 knives were issued to field medical soldiers as the United States entered World War I in 1917.

The second knife is less bolo and more machete in its design. The M1910 bolo was designed and implemented for use as a brush-clearing tool. Some collectors reference the M1910 as a machine-gunner’s bolo as it was employed by the gun crews and used to clear machine gun nests of foliage and underbrush. My M1910 bolo is date-stamped 1917 and includes the correct leather-tipped, canvas-covered wooden scabbard.

- This 1944-dated USMC bolo and scabbard are a cherished part of my collection.

- The blade and hilt of the USMC World War II bolo.

The last bolo in my collection is probably the most sought-after of the three examples. Stamped U.S.M.C. directly on the blade, these knives were issued to U.S. Navy pharmacist’s mates who were attached to U.S. Marine Corps units. This detail leads many collectors to improperly conclude that the markings on the blade clearly indicate that the knives were made for the Marines. While this is indirectly true, the U.S.M.C. markings represent the United States Medical Corps, a branch of the U.S. Navy. On the reverse side, the blade is date-stamped, “1944” making the blade clearly a World War II-issued knife.

Although the blades are relatively inexpensive, they are considerably valuable to me as they come from a family member’s collection and were handed down to me. Though I do not have a desire to delve too far into edged weapons-collecting, I added to my collection by acquiring a pair of US Navy fighting knives to round out my collection. In future posts, I will cover these two types of knives, swords and sabers and even a few bayonets.