Category Archives: World War II

Drawing in Recruits: Posters and Broadsides

Tonight, as I was finishing up some research for one of my genealogy projects, I found myself clicking through a series of online auction listings of militaria that would look absolutely fantastic hanging on the walls of my “war room.” My mind began to wander with each page view, imagining the various patriotic renderings, designed to inspire the 1940s youth to rush to their local recruiter to almost single-handedly take on the powers of the Axis nations.

Originally created for Ladies Weekly in 1916, the iconic image of Uncle Sam was incorporated into what is probably the single, most popular recruiting poster that began its run during WWI (source: Library of Congress).

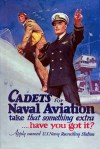

Rather than focusing on the raging war in Europe, this Charles Ruttan-designed poster demonstrates the career and travel opportunities.

Recruiting posters are some of the most collected items of militaria as their imagery conjures incredible emotional responses, such as intense national sentiment, inflamed hatred of the new-found enemy or a sense of call of duty. The colorful imagery of these posters inspires considerable interest from a wide range of collectors, in some cases driving prices well into four-digit realms.

Most Americans are familiar with the iconic imagery of Uncle Sam’s “I Want YOU for the U.S. Army” that was created and used in the poster by James Montgomery Flagg, making its first appearance in 1916, prior to the United States’ entry into World War I. While this poster is arguably the most recognizable recruiting poster, it was clearly not the first. Determining the first American use of recruiting posters, one need not look any further than the Revolutionary war with the use of broadsides, one of the most common media formats of the time.

The use of broadsides, some with a smattering of artwork, continued to be utilized well into (and beyond) the Civil War with both the Army and Navy seeking volunteers to fill their ranks. With the advancement of printing technology and the ability to incorporate full color, the artwork began to improve, adding a new twist to the posters, providing considerable visual appeal. By the turn of the twentieth century, well-known artists were commissioned to provide designs that would evoke the response to the geopolitical and military needs of the day.

- Known as a broadside, this poster mentioned that able-bodied men that were not headed for Army ranks would be enlisted into Naval service.

- This is a beautiful example of a Revolutionary War broadside is recruiting soldiers for service in General Washington’s Army for Liberties and Service in the United States (source: ConnecticutHistory.org).

Adding to the appeal for many non-militaria collectors is artist cache associated with many of the recruiting poster source illustrations. The military brought in the “big guns” of the advertising industry’s graphic design, tapping into the reservoir of well-known artists; if their names weren’t known, their stylings had permeated into pop culture by way of ephemera and other print media advertising. In addition to James Flagg, some of the most significant (i.e. most sought-after and most valuable) Navy recruiting posters were designed by notable artists such as:

- Howard Chandler Christy’s famous “Christy Girl” poster from World War I.

- This sailor extends his hand to would-be recruits encouraging them to climb aboard and join the fight. McClelland Barclay incorporated his advertising industry experience in graphic-design and style into these recruiting posters.

- The Naval Construction Battalion (CB or “Sea Bees”) was proposed in 1941 and established immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack. This poster (illustrated by John Falter) was used to attract journeymen construction tradesmen who would build all of the bases and airfields used to push the Japanese back to their homeland, one island at a time.

- Another McClelland Barclay poster showing a naval aviator climbing into his open-cockpit aircraft with a battleship mast and superstructure showing in the background.

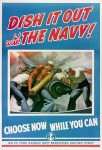

- These sailors rapidly load the naval gun as they are actively engaged in combat. This imagery (by McClelland Barclay) was designed to fan the flames of nationalism and nudge those seeking to avenge the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Sadly, with my limited budget and my unwillingness to horse-trade any of my collection, these posters are somewhat out of my reach. It goes without saying that condition and age along with desirability have direct impact on value and selling prices. Some of the most desirable posters of World War II can sell for as much as $1,500-$2,000. For the collector with deeper pockets, Civil War broadsides can be had for $4,500-$6,000 when they become available. I have yet to locate any of the recruiting ephemera from the Revolutionary War, so I wouldn’t begin to speculate the price ranges should a piece come to market.

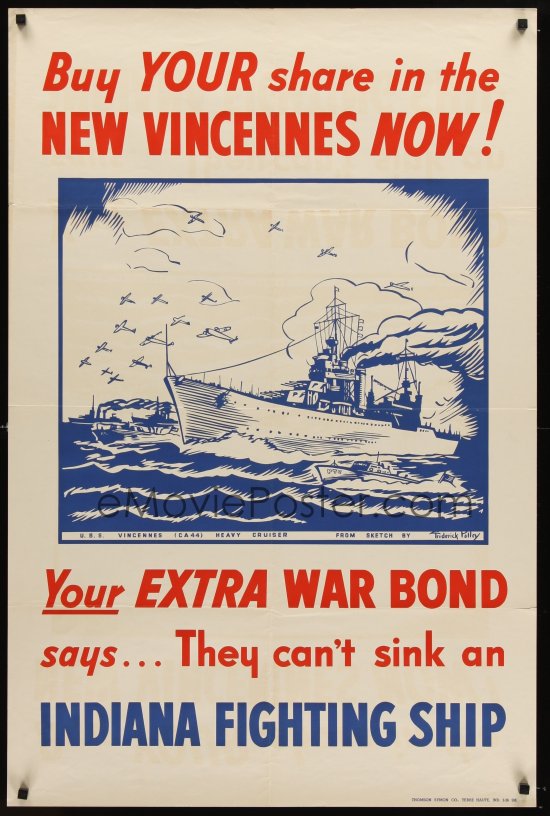

The citizens of a small Indiana town (Vincennes) raised enough money through a successful bond drive to meet the Secretary of the Navy’s financial requirement which resulted in the already under construction light cruiser (CL-64) to be named Vincennes.

Discouraged as I may be in my quest to secure one of these treasured prints, I may be better off seeking quality reproductions to adorn the vertical white-space of my war room. However, a few years ago I received a reproduced war-bond drive poster – the original was created to encourage Hoosiers to buy bonds to name a new cruiser to honor the (then) recently sunk USS Vincennes.

Note: All images not sourced are provided courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command

Calculated Risks: Bidding on Online Auctions that Contain Errors

Regardless of how much knowledge you may possess, making good decisions about purchasing something that is “collectible” can be a risky venture ending in disappointment and being taken by, at worst, con-artists or at best, a seller who is wholly ignorant of the item they are selling. Research and gut-instinct should always guide your purchases for militaria. Being armed with the concept that when something is too-good-to-be-true, it is best to avoid it. I recently fell victim to my own foolishness when I saw an online auction listing for an item that was entirely in keeping with what I collect.

I am very interested in some specific areas of American naval history and one of my collecting focus centers around a select-few ships and almost anything (or anyone) who might have been associated with them. One of those ships (really, four: all named to honor the Revolutionary War battle where American George Rogers Clark was victorious in Vincennes, IN), the heavy cruiser USS Vincennes (CA-44) is one in particular that I am constantly on the lookout for.

- The auction listing is innocuous; albeit accurate. However, the details are where this seller’s words are misleading and troublesome.

- Note in the description that the seller lists specifics about the book (nothing the title, author and edition). Sadly, this is a farse.

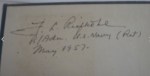

- There were two factors that led me to purchase this book: Admrial Riefkohl’s signaturem that it was in, what I consider to be one of the most accurate accounts of the Savo Island battle.

In early September (2016), a listing for an item that surfaced in one of my saved searches results, caught my attention on eBay. The auction description made mention of a book, Savo: The incredible Naval Debacle Off Guadalcanal, that happens to be one of the principle, reliable sources for countless subsequent publications discussing the August 8-9, 1942 battle in the waters surrounding Savo Island. Though I read this book (it was in our ship’s library) years ago, it is a book that I wanted to add to my collection but until this point, never found a copy that I wanted to purchase. What made this auction more enticing was that this book featured a notable autograph on the inside cover. In viewing the seller’s photos, I noted that the dust jacket was in rough shape but the book appeared to be in good condition (though the cover and binding were not displayed). There were no bids and the starting price was less than $9.00.

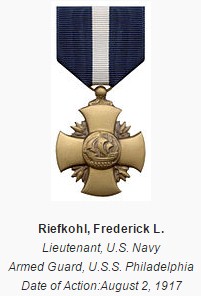

Riefkohl was awarded the Navy Cross medal for actions performed aboard the USS Philadelphia against German submarines during WWI convoy escort operations (see the test of the accompanying citation below).

I have been a collector of autographs and have obtained several directly from cultural icons (sports stars, actors, musicians) but my favorites are of notable military figures (recipients of the Medal of Honor [MOH] and other servicemen and women) who distinguished themselves in service to our country. The signature in this book featured a retired naval officer who was the recipient of the Navy’s highest honor, the Navy Cross (surpassed only by the MOH) and who played a significant role in the Battle of Savo Island as he was the commanding officer of the heavy cruiser, USS Vincennes (CA-44) and the senior officer present afloat (SOPA) for the allied group of ships charged with defending the northern approaches (to Savo and Tulagi islands). Frederick Lois Riefkohl (then a captain) commanded the northern group which consisted of four heavy cruisers; (including Vincennes) USS Quincy (CA-39), Astoria (CA-34) and HMAS Canberra (D33).

By all accounts, the Battle of Savo Island (as the engagement is known as) is thought to be one of the worst losses in U.S. naval history (perhaps second only to the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor) as within minutes of the opening salvos by the Japanese naval force, all four allied ships were left completely disabled and sinking (all would succumb to the damage and slip beneath the waves in the following hours). Though the loss was substantial, the Japanese turned away from their intended targets (the allied amphibious transport ships that were landing marines and supplies on Guadalcanal and Tulagi) missing a massive opportunity to stop the beginnings of the allied island-hopping campaign. The First Marine division was permanently entrenched on these islands, and would drive the Japanese from the Solomons in the coming months.

Captain Frederick Lois Riefkohl (shown here as a rear admiral).

Captain Riefkohl was promoted to Rear Admiral and retired from the Navy in 1947 having served for more than 36 years. He commanded both the USS Corry (DD-334) and the Vincennes and having served his country with distinction, the Savo Island loss somewhat marred his highly successful career.

As I inspected the book, there were a few aspects that gave me reason for pause. First, the seller described the book as “SAVO by Newcomb 1957 edition” which left me puzzled. Secondly, the Admiral included a date (“May 1957”) with his signature. Recalling that Newcomb’s book was published in 1961 ( See: Newcomb, Richard Fairchild. 1961. Savo. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.), I was a bit dismayed by the four-year discrepancy between the date of the autograph and (what the seller determined to be the) first edition published date. I wondered, “how did he determine this date and where did he find this information?” I noted that there was no photograph of the book’s title page accompanying the auction.

I decided to take a gamble that at worst, would result in me spending a small sum of money for an autograph that I wanted for my collection and at best was merely a fouled up listing by an uninformed seller. I pulled the trigger and my winning bid of $8.99 had the book en route (with free shipping, to boot)!

The dust jacket is in very rough shape with tears, creases, cracks, shelf wear and dog-ears. The cover art is fairly intense in conveying what took place in the battle.

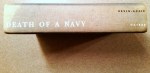

The confirmation that I didn’t want; this book turned out to be”Death of a Navy” which isn’t worth investing time to read as it is known to be a rather erroneous work.

Nearly two weeks later, the package arrived. I reservedly opened the packaging and freed the book from the layers of plastic and bubble wrap. I inspected the ragged dust jacket and removed it to see the very clean cover which didn’t seem to match. I opened the book and viewed Riefkohl’s autograph which appeared to match the examples that I have seen previously. I turned to the title page and confirmed my suspicions. Death of a Navy by an obscure French author, Andrieu D’Albas (Captain, French Navy Reserve). “Death” is not worthy enough to be considered a footnote in the retelling of the Pacific Theater war as D’ Albas’ work is filled with errors. By 1957 (when this book was published), most of what was to be discovered (following the 1945 surrender) from the Japanese naval perspective was well publicized before the start of the Korean War. It is no wonder why Andrieu D’Albas published only one book.

- Death of a listing. This acquisition turned out to be a partial dud.

- Removing the dust jacket, the cover didn’t seem to match the dust jacket.

My worst-case scenario realized, I now (merely) have the autograph of a notable U.S. naval hero in my collection. While I could have gone with my gut feelings about the auction listing, having this autograph does offset my feelings of being misled (regardless of the seller’s intentions).

Admiral Riefkohl’s signature appears to be authentic leaving me semi satisfied in that I obtained a great autograph for my collection.

Riefkohl’s Navy Cross Citation:

The Navy Cross is awarded to Lieutenant Frederick L. Riefkohl, U.S. Navy, for distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commander of the Armed Guard of the U.S.S. Philadelphia, and in an engagement with an enemy submarine. On August 2, 1917, a periscope was sighted, and then a torpedo passed under the stern of the ship. A shot was fired, which struck close to the submarine, which then disappeared

Strange Gold: A Tooth with a Story

Merriam Webster defines History as:

1: tale, story

2a: a chronological record of significant events (as affecting a nation or institution) often including an explanation of their causes

b: a treatise presenting systematically related natural phenomena

c: an account of a patient’s medical background

d: an established record <a prisoner with a history of violence>3: a branch of knowledge that records and explains past events <medieval history>

4a: events that form the subject matter of a history

b: events of the past

c: one that is finished or done for <the winning streak was history> <you’re history>

d: previous treatment, handling, or experience (as of a metal)

The very first definition; the first word used to define history is quite interesting.

Tale:

1 obsolete : discourse, talk

2a : a series of events or facts told or presented : account

b (1) : a report of a private or confidential matter <dead men tell no tales> (2) : a libelous report or piece of gossip3a : a usually imaginative narrative of an event : story

b : an intentionally untrue report : falsehood <always preferred the tale to the truth — Sir Winston Churchill>

Dick Portillo, shown with military memorabilia in his Oak Brook office Sept, 8, 2016, is on a quest to determine whether a gold tooth discovered on a Pacific island is that of Japanese Cmdr. Isoroku Yamamoto, who planned the Pearl Harbor attack and who was shot down in 1943. (Terrence Antonio James / Chicago Tribune)

Collectors of militaria are always fascinated by the pieces within their collection. (They) we are constantly seeking the history of each object to:

- Connect collection items to historical persons

- Understand how the object is contextually associated to an event or events

- Increase intrinsic value in order to resale an item for profit and financial gain

The idea of being in possession of an item that was carried, worn or used during a significant historical event – a pivotal battle or a crippling defeat – helps to connect the person holding, touching or viewing the object to history in a very tactile manner. Many of my collector colleagues possess pieces in their collections that would be centerpieces of museums due to their historical significance. In my own collection, I have a few pieces that are connected to notable events but not on the order magnitude (of the subject) of this article.

A gold tooth discovered on a Pacific island could be that of Japanese Cmdr. Isoroku Yamamoto. (Terrence Antonio James / Chicago Tribune)

I wrote an article where I focused on the odd and strange militaria items that would otherwise seem bizarre (for anyone to collect) to laymen and casual observers. Yesterday, I read a Chicago Tribune article (Does Chicago hot dog king have WWII Japanese admiral’s gold tooth? – by Ted Gregory, September 18, 2016) that captured my immediate attention. The compelling tale about a team of eight history enthusiasts that made their way to Papua New Guinea, trekked through the dense jungle to Admiral Yamamoto’s plane crash site and by chance, located a gold-encased tooth in the well-picked-over Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” attack bomber. This story seemed to dovetail quite nicely into what I discussed in my previous article – that a tooth from a deceased “enemy” hero certainly fits my idea of a militaria collection oddity.

- The Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber.

- The fuselage of the Imperial Japanese Navy bomber aircraft that was carrying Admiral Yamamoto.

- Part of the wreckage of Yamamoto’s IJN “Betty” aircraft.

To be in the possession of the tooth of a long-dead Japanese “god-like” hero from World War II would be exciting yet somewhat morbid. However, I am rather skeptical as to the potential of the item that was recovered at the crash would be Yamamoto’s (there were eleven men aboard this aircraft) yet I agree that the possibility does exist. There are conflicting reports as to the status of the Admiral’s body when discovered: Early documents (from the IJN doctor who examined the deceased Admiral) mention only a chest-area gunshot wound and that his body was otherwise intact. It was mentioned that other than the obvious mortal wound, Yamamoto appeared to be sleeping, still buckled into his seat, clutching his katana. Subsequent reports mention a substantial gunshot wound to his jaw (which could have dislodged the tooth in question).

The man who is in possession of the tooth, Dick Portillo (if you have never eaten at the restaurants that he founded and recently sold, you are missing out), who purchased the tooth from the owners if the crash site, is hopeful to be able to successfully extract and match the DNA of the tooth to the Admiral in order to authenticate his claim. I question the willingness of the Japanese government and Yamamoto’s decedents to participate in Portillo’s efforts, and if they do, what their motivation would be.

Until any authentication of the tooth is completed, the tooth resides in the collection of Dick Portillo along with what appears to be a wonderful selection of arms (as is visibly displayed on his office wall). If validated, Portillo said that he will give the tooth to the Japanese government, most likely to be repatriated (perhaps to be part of the Isoroku Yamamto Memorial Museum collection). I wonder what will become of the tooth if there is no cooperation or if it proves to be from another passenger of the Betty? Will it remain a part of his collection – a piece of history with two stories (Portillo’s and the Japanese passenger)?

References:

- Pacific Wrecks: G4M Model 11, Betty (manufacture #2656, Tail # T1-323)

- Operation Vengeance

- Video: Yamamoto’s Wreck Site

- Aces Against Japan: The American Aces Speak

- Lightning Strike: The Secret Mission to Kill Admiral Yamamoto and Avenge Pearl Harbor

- The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944-1945