Category Archives: World War II

A Uniform for an Ordinary Joe

There are times when I find myself with so many topics to write about that my mind wanders so rampantly that I am left with seemingly nothing to cover. It is akin to my wife walking into our closet (that is filled with clothes) and finding nothing to wear.

I look back on all that I have covered during the past 15 months (including my year of writing for CollectorsQuest) in an attempt to avoid repeating myself. I check my collection for items that I haven’t covered yet (there is an abundance at the moment) while looking ahead at some event/calendar-based ideas that I am working on and I realize that I can begin to narrow the field a little. I can focus in on a subject knowing that as this article begins to develop, it may very well transform into something vastly different when I am ready to publish it.

Speaking of closets filled with nothing to wear, there among the garments that I rotate through each week are several garment bags packed full of military uniforms. While some of the uniforms were worn during my naval career and a few others belonged to my grandfather, the lion-share are truly pieces in my modest collection (dominated with U.S. Navy uniforms). Looking at the last few articles that I’ve written for this blog are Navy-focused, I am pushed toward covering one of the two non-Navy uniforms in my possession.

Why collect uniforms someone (new to militaria collecting) might ask? For me at least, the idea of possessing a tangible object that was worn by a service member (especially during a significant period of our nation’s history) provides a sensory connection (sight, scent, touch) that is unattainable with written words or images. In addition, the uniforms themselves possess some elements and characteristics that make them, on their own, aesthetically pleasing.

My uniform collection, when compared with that of other (long-term) collectors, is quite humble and ordinary when it comes to the identities of the veterans who previously owned and wore the items. This is not to suggest that anyone’s service to this country is ordinary, but in comparison to veterans whose careers shaped and impacted history (so much so that their names are legendary because of their battlefield deeds), my uniforms are quite modest.

One colleague owns (or owned) uniforms that would make almost any collector salivate at the mere thought of touching, let alone owning. Imagine having the uniform from the man who, while in command of a diminutive destroyer escort, bore down on Japanese task force that consisted of four battleships (including the Yamato), eight cruisers and several destroyers in order to protect the carriers in his own task force? That commanding officer, Robert Copeland risked himself, his ship and his crew in order to successfully protect the American carriers from certain destruction near Samar in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Copeland received the Navy Cross for his actions that day in October of 1944.

Post-World War II Khaki uniform jacketm dress blues and combination cover, worn by Navy Cross recipient, Admiral Robert Copeland (image source: ForValor.com/Dave Schwind)

This World War I – era U.S. Navy frock coat belonged to (then) Captain Frank Schoflield. Note the ornate bullion collar devices and the pre-WWI sewn-on ribbons (image source: USMilitariaForum.com/Dave Schwind).

The shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) for the 1st Marine Division. This patch is affixed to the left shoulder of a 1943-dated USMC uniform jacket.

Not everyone has the finances or the perfect timing to locate items from such legendary people. Some collectors seek uniforms that serve to illustrate a story or, perhaps to demonstrate the progression of uniform changes throughout history. In either case, high-dollar uniforms from well-known figures (of American history) would serve to highlight such a story line but are not necessarily needed pieces. For those who (with limited budgets) want to pursue something from a specific (i.e. monumental) period of military history, “settling” for uniforms from the common soldier, airman, sailor or Marine.

I am particularly interested in the history surrounding the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO) when discussing or researching World War II. Being a Navy veteran and the grandson of a WWII PTO Navy veteran, my collection tends to be focused in this area. I’ve taken considerable interest specifically in the southern Solomon Islands and the battles (both on land and sea) that took place in the surrounding area. When many people think of this region, immediate thoughts of Guadalcanal and the saga of the First Marine Division’s legendary fight (and “abandonment” by the U.S. Navy following substantial vessel losses on August 8-9, 1942 near Savo Island). When a WWII USMC uniform from a 1st MarDiv veteran became available (at an affordable price), I didn’t hesitate to pull the trigger on a purchase.

In stark contrast to the two Navy legends’ uniforms above, this nameless jacket was from a humble PFC of the 1st MarDiv.

Everything about this jacket is superb. Not a single moth hole and all of the buttons are present.

As a research project – trying to determine the service and experiences of the original owner – it possesses next-to-nothing that would afford me a path to pursue. The only identifying marks in the uniform jacket were three initials, “G. E. M.” The odds that I could pinpoint a veteran in the 1st Marine Division with those three letters makes the challenge daunting, to say the least. At this point, I haven’t had the time or desire to begin such an endeavor leaving the uniform to simply fill a space within my collection. I am happy just to own this uniform with the idea that this private first class Marine possibly served in one or more of the notable battles alongside the his brothers in The Old Breed.

To locate the uniform label (which contains the contract and date data) as well as identification marks left by the original wearer, check the inside of the left sleeve.

Immediately beneath the uniform label, the initials “G. E. M.” could correspond with the original owner’s name. Locating this marine would be next to impossible.

Related Uniform Topics:

All images are the property of their respective owners or M. S. Hennessy unless otherwise noted. Photo source may or may not indicate the original owner / copyright holder of the image.

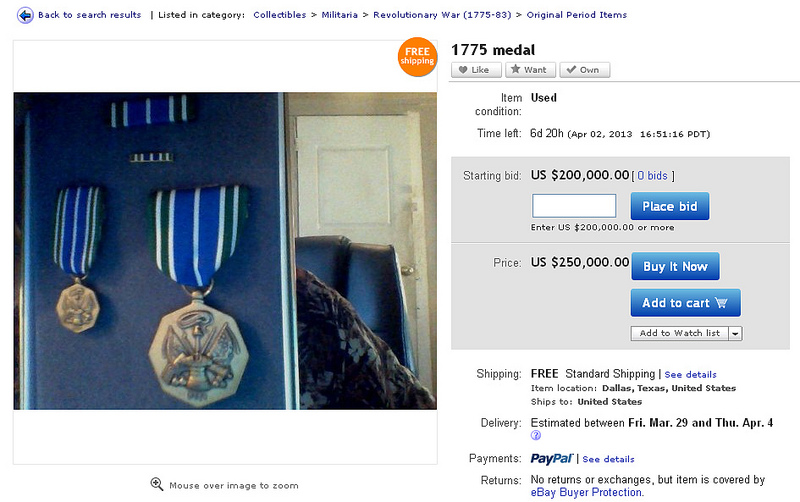

Happen to Have $250k for a “Rare” 1775 Medal?

Having a sense of humor is a good thing for those of you who have served (or are serving) in uniform. You understand the necessity…no…the requirement of possessing the invaluable ability to laugh at humorous situations but also actions, activities, operations or events that are FUBAR (you can look that term up if you don’t already know the definition). With regards to militaria collecting, sarcasm, eye-rolling, head-shaking and bursting forth with gut-shaking laughter helps to keep things in proper perspective, especially when one stumbles upon situations like the following.

I know that many, if not most of the people reading this have little or no background covering the history of the United States military medals and decorations. In order to provide some sort of baseline which will then help you to either laugh, roll your eyes or shake your head in disbelief with some measure of authority, I will provide brief history lesson. I won’t go into great detail with the intricacies and extremely specific minutiae so (for those you who are OMSA members) give me a little latitude as I provide a “Reader’s Digest” version.

The Fidelity Medallion was authorized by Congress in 1780 and awarded to three soldiers of the Continental Army.

Prior to the Declaration of Independence and the subsequent military action taken by the rebellious colonists of North America, awards and decorations were a tradition of European militaries predominantly awarded to the senior military leaders and heads of state to commemorate victorious aspects of their illustrious careers. For the first five years of the Revolution, no decoration existed for men who served in the Continental Army or Navy as, it would seem that winning independence from the tyrannical British rule would be enough (aside from being paid for service) to risk life and limb.

Presented by General Washington, the Badge for Military Merit was awarded to at least three army soldiers.

It wasn’t until 1780 that Congress enacted the very first decoration, the Fidelity Medal, which was awarded to three specific militiamen (John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart and David Williams) who captured British intelligence officer, Major John Andre’ (who was assisting Benedict Arnold in his treasonous act). Aside from a few Congressional actions taken to award medals to General George Washington (1776), General Horatio Gates (1777) and General Henry Lee (1779), the first medal awarded to soldiers was initiated by the issuance of a field order by General Washington on August 7, 1782 establishing the Badge of Military Merit. There is some debate as to the number of recipients of the Badge of Military Merit (the predecessor of the Purple Heart medal), but there were very few soldiers to have it bestowed upon them (as few as three).

Another military decoration wouldn’t be awarded for 65 years when the Certificate of Merit (officially recognized with a medal in 1905) was enacted by Congress during the Mexican-American war, in 1847 and re-established during the Indian Wars in the second-half of the nineteenth century.

This Navy Type 1 Civil War-era Medal of Honor was presented in 1864 (source: Naval History & Heritage Command).

The most notable American military decoration, the Medal of Honor, was established during the Civil War with the first official presentation taking place on March 25, 1863 decorating six Union Army soldiers with the medal. From the Civil War on through World War II, the process of enacting, creating, managing and awarding military decorations was a process that required developing and maturing as awards manuals and official procedures and precedents were established. For military novices, online resources are quite plentiful and very useful for learning how to determine the identity of a specific decoration and it’s potential collector demand and subsequent value. Now that I have presented all of this information, it is my hope that you see the humor in the remainder of this article.

The Army Achievement Medal was established in 1981 and is awarded for outstanding achievement or meritorious service.

In 1961, the Navy Department established a medal to recognize individual, meritorious achievements that were not commensurate with the criteria of the Navy Commendation medal. In 1981, the Army (and Air Force) followed suit with their own achievement medals.

The design of the Army Achievement medal obverse is somewhat generic as it depicts the official U.S. Army seal along with the year the Continental Army was established (1775). The reverse of pendant simply states, “For Military Achievement.”

In a recent online auction listing, a seller listed a military decoration and titled it “1775 medal” and listed it as an Original Period militaria Item from the Revolutionary War (1775-83). The photo of the medal showed it as a set (ribbon device, lapel pin, miniature and full sized medals) in the current-issue plastic presentation case. One could suppose that the seller simply mis-categorized the listing and perhaps, mistyped the auction title. These sorts of mistakes are quite common occurrences. However, this story doesn’t end with a simple mistake.

This auction is humorous regardless if the seller believes the medal is 240 years old or simply being sarcastic (source: eBay screenshot).

Reviewing the 1775 medal auction description and price, it should become readily apparent that the seller is either out of his or her element, seeking to deceive a potential buyer or having some fun with an online auction listing. The seller states in the text, “1775 military achievement award complete set asking 200,000 worth 350.000 (sic).” Fortunately for potential buyers, the seller provided an option to buy it now for $250k, splitting the difference between the starting bid and the (stated) value.

Either the seller thinks this medal is only worth $350 but is selling it for a mere $200k or potential buyers can save as much as $150k submitting his minimum bid (source: eBay screenshot).

Not one to make accusations as to the seller’s intentions, I choose to instead, laugh and enjoy the antics routinely experienced in the world of online auctions. For the record, if a collector is seeking to purchase an Army Achievement medal set, look to pay in the neighborhood of $20-40.

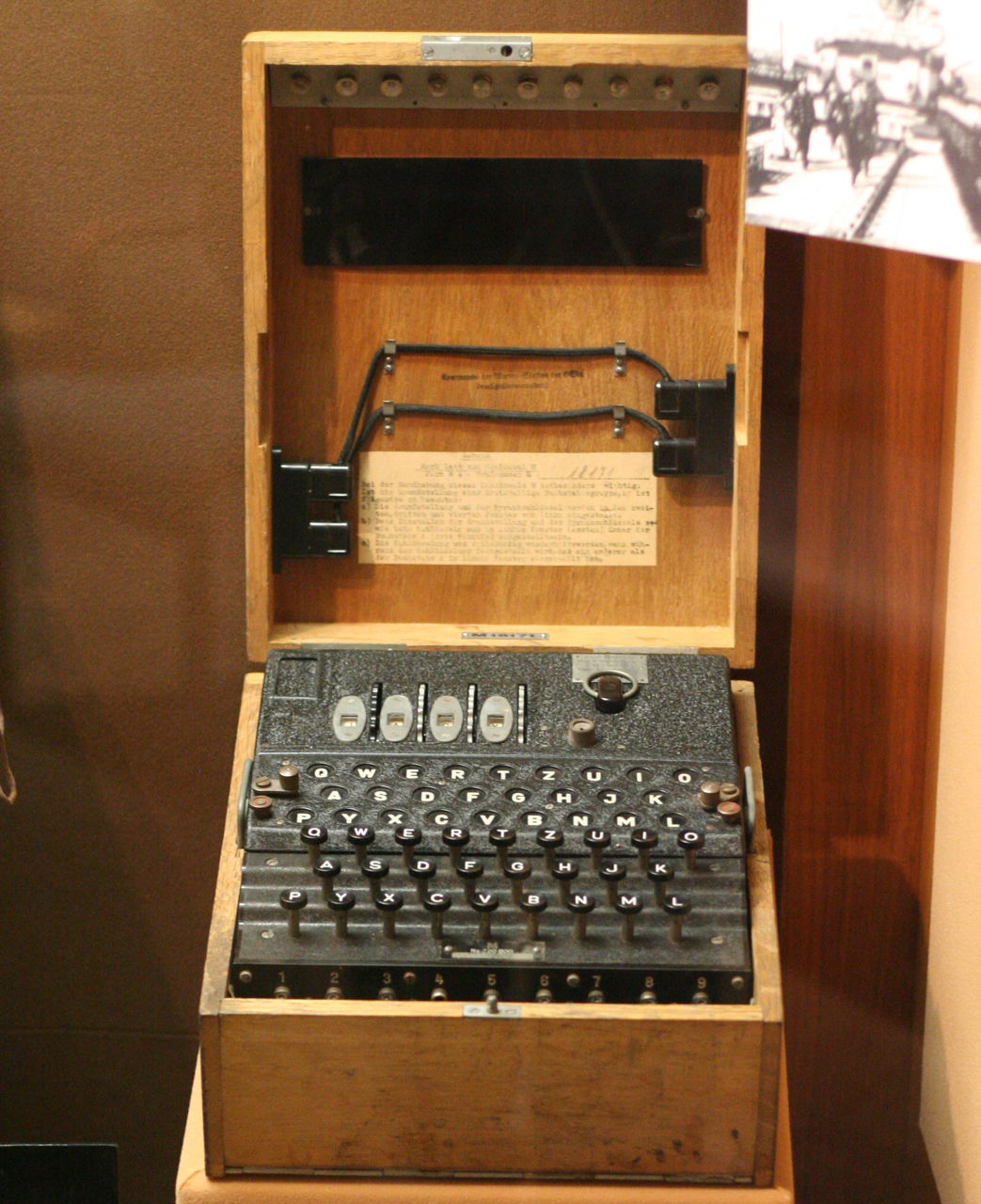

The Enigmatic pursuit of the Third Reich Encryption Machine

History is continuously subjected to revision as stories are told and retold. Researchers and historical experts are seemingly discovering previously hidden facts or secrets that shed new light on events. With the new revelations, previous facts surrounding historical events are skewed or changed causing a re-shaping of timelines and ultimately public perception. Hollywood however, seems bent on taking a different tack with regards to revising history in order to reshape producers’, directors’ and actors’ bank accounts.

This scene shows the disguised American sub (“S-33”) meeting with the U-571 in a rouse to obtain the Enigma code machine (source: Universal Pictures).

In April of 2000, Universal Pictures released a highly successful historical-fiction movie depicting the U.S. Navy’s successful capture of a Kriegsmarine u-boat during World War II. The premise of the film was centered on seizing the keystone encryption device (often referred to as Germany’s “secret weapon”), the Enigma encode/decoding machine along with the codes. While director Jonathan Mostow (who also co-wrote the screenplay) navigates around the historical truths by conveniently mentioning that the story is a compilation of actual events rather than being based on a true story. While this may have worked for American audiences, Great Britain’s Prime Minister (at the time of the film’s release), Tony Blair agreed with discussion (about the film) in Parliament that the story was an affront to the British sailors who gave their lives in the actual retrieval of the Enigma device during the war.

Rather than embarking on a mission to demonstrate the challenges created by Hollywood’s propensity of altering reality (albeit for entertainment purposes), I want to focus more on the capture of the machine and codes and what that meant for achieving an Allied victory over the Axis powers during World War II.

Prior to the United States’ entry into WWII on December 8, 1941, Europe had already been gripped with conflict for twenty-five months. Though it was a highly protected secret, the Allies were fully aware of the existence of the Enigma machine and had already seen successful code-breaking efforts (by the Polish Cipher Bureau in July of 1939) until continued German technological advances rendered those efforts obsolete. It wasn’t until May 9th, 1941 that the Allies achieved their most substantial breakthrough with the British capture of U-110 along with codes and other intelligence materials.

One of the events that is allegedly covered (by the U-571 film) is the United States’ capture of the U-505 in 1944 (three years after U-110) which was towed to Bermuda. Following the war, the U-boat was towed to Portsmouth Navy Yard, New Hampshire where she sat until being transported to Chicago to be displayed as a museum ship. The U-505 is now preserved inside the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Also on display are two Enigma code machines.

In addition to the two machines in the Chicago MOSI, there are a handful in museum collections around the globe. Due to the scarcity of the devices, their notoriety and the impact of their capture had on the outcome of the war, Enigmas command incredible premiums when they surface on the market. As recent as 2011, a Christies’ listing yielded a sale with the winning bid in excess of $200,000.

This Enigma’s selling price was in excess of $35,000 (US) when it was listed at auction in March of 2013 (source: eBay image).

Most recently, the winning bid for an online auction listing (for a three-disk Enigma) seemed to reflect a more modest price as it sold for “only” $35,103. One has to wonder why, in only two years, would there be such a considerable price disparity (obviously factoring model, variant, condition, etc.) between the two transactions. Perhaps the current state of the economy is at play? Maybe the collector or museum with deep pockets was eliminated from the market with their purchase in 2011? Perhaps the $200k selling price was an anomaly and this recent auction reflects a more realistic value?

Either way, the Enigma will remain…well…just that…an enigma with regards to my own collection and the possibility of ever possessing one.

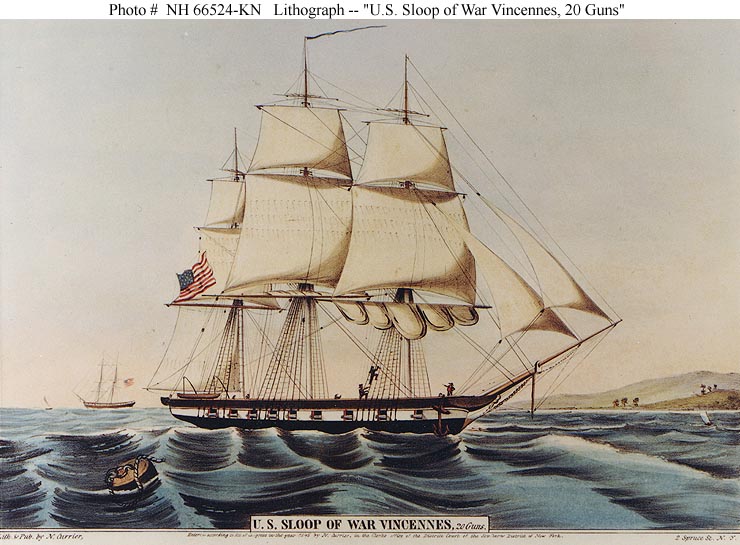

USS Vincennes Under the Microscope

Those who know me on a personal basis understand my affinity for a specific U.S. naval warship. Technically speaking, that interest lies with four combatant vessels, all of which were named to honor the site of a Revolutionary War battle (more accurately, a campaign) that ended the British assaults on the remote Western colonial front. That location in present-day Southwestern Indiana would later become the seat of the Northwest Territorial government in the town of Vincennes.

Colored lithograph published by N. Currier, 2 Spruce Street, New York City, 1845 (source: Naval Historical Center).

My connection to this ship’s name extends all the way back to the place of my birth which was also the location of the commencement of an extensive 1840 charting survey of Puget Sound (in Washington State). Locations and geographical features surrounding my home were named by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (commander of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842) and members of his team when the sloop of war, USS Vincennes (along with other ships of the expedition) was in the Sound. I can even cite some Baconesque connections with great, great, great-grandfather who served in the Ringgold Light Infantry (after he was discharged from his cavalry regiment following a disabling injury). The Ringgold name was inherited from Samuel Ringgold, Expedition-member Cadwalader’s older brother (yes, I realize that this is very convoluted).

My personal connection (to the ships named Vincennes) was solidly established when I was assigned to the pre-commissioning crew of the CG-49. During the first several months (leading toward the 1985 commissioning date), like many of my shipmates, I was exposed to the history of the ship’s namesake and established personal relationships with veterans of the WWII cruisers of the same name. Collecting items from “my” ship was purely functional in that I was proud to purchase t-shirts, lighters, ball caps and other items (from the ship’s store) that bore the name or the image of the ship’s crest. Many of the items I purchased in those days proudly remain in my collection while a few did manage to fade away.

I am constantly on the lookout for artifacts that are connected to these ships (the heavy cruiser: CA-44, the light cruiser: CL-64) and occasionally, some quality pieces (beyond the plethora of typical postal covers) surface on the market. Fortunately, I have been successful in obtaining a few of these items, though the competition has been fierce. The ones that got away were quite stunning.

William D. Brackenridge was the assistant botanist for the U.S. Exploring Expedition serving aboard the USS Vincennes from 1838-1842.

The infrequency of appearances of pieces from the two WWII cruisers pales in comparison to anything related to the 19th Century sloop-of-war. During the past decade of searching for anything related to the USS Vincennes, I have only seen one item connected to the three-masted warship. While searching a popular online auction site, a rather ordinary, non-military item showed up in the search results of one of my automated inquiries. The piece, a wood-cased field microscope from 1830-1840, bore an inscription that connected it to the assistant botanist of the United States Exploring Expedition, William Dunlop Brackenridge.

Admittedly, I am not in the least bit interested in a field microscope as militaria collector, but the prospect of owning such a magnificent piece that would have been a fundamentally important tool used during the United States first foray into exploration was an exhilarating thought. At its core, the goal of the (1838-1842) U.S. Ex. Ex. was to chart unknown waters, seek the existence of an Antarctic continent and discover and document unknown species of flora and fauna. Brackenridge’s field microscope would have been a heavily used item as he and his assistants would most-certainly examine the various characteristics of plant species at a microscopic level.

The box appears to be missing some of the securing hardware which would help to hold the lid closed (source: eBay image).

Authenticity and provenance is certainly a major concern when purchasing a piece like this and the listing made no mention of any materials or means to verify the claim. However, in searching for similar microscopes, there was sufficient comparative evidence to support the time-frame in which the Brackenridge instrument was made. The box and the engraving seems to be genuinely aged and appears to resemble what one would find from a 170 year old example.

The box for the field microscope is inscribed with “Property of W. D. Brackenridge U.S.S Vincennes 1840″(source: eBay image).

In my opinion, the investment was well-worth the risk and I was poised to make my maximum bid (invariably draining my discretionary savings) knowing that the closing price would exceed what I could ultimately afford. The auction closed with the winning bid ($810.58) exceeding my funds by a few hundred dollars, though I suspect that the winner had a far higher bid in place to guarantee victory.

I am a realist yet remain hopeful that I won’t have to wait another decade before another sloop-of-war piece comes to market.