Category Archives: World War I

Introductory Flight – Collecting Aviator Wings

From the top: Command Pilot, Senior Pilot and Pilot of the US Army Air Force. The naval aviator “wings of gold” are really set apart from its USAAF counterparts.

Since the early twentieth century, all of the branches armed forces of the United States have been bolstered by service men and women who are highly skilled, reaching the pinnacle of their specialized area of expertise. From aviators, to paratroopers, to submarine crew members and combat infantrymen, all are easily recognizable by the devices and pins affixed to their uniforms.

Since the advent of military flight and the employment of aviators in war-fighting aircraft, leadership within the ranks realized that there was a need to provide a uniform accouterments to set these special and unique servicemen apart from the rest of those in uniform.

During World War I, the Air Service (U.S. Army) began issuing qualified pilots a winged pin device to attach to the left breast of their uniform blouse. The device was constructed in silver-colored metal (mostly silver or sterling silver or embroidered in silver bullion thread) with two ornately feathered bird wings attached to either side of a shield, which had 13 stars in a field over 13 stripes. Superimposed over the shield were the letters, “U.S.” This wing design would remain in use throughout the Great War.

A nice example of a World War i balloon pilot’s single wing of the Army Air Service.

During the interwar period (1919-1941), the U.S. Army Air Corps wings were more standardized, dropping the U.S. lettering and simplifying the design. The shape of the shield became more standardized though it would vary depending upon the manufacturer. The Air Corps also began introducing varying degrees of the pins that signified the experience of the aviator. In addition to the existing pilot badge, the senior pilot (which added a five-point star above the shield) and command pilot (with a five-point star inside a wreath) badges were issued.

This stunning 8th Air Force 2nd Lieutenant’s uniform has a beautiful example of a silver bullion wing. In fact, all of the (typically metal) devices are made from silver bullion thread.

- World War II Army Pilot Wing Variants

- World War II Army Senior Pilot Wing Variants

- World War II Army Command Pilot Wing Variants

This display features WWII USMC ace, Major Bruce Porter’s decoration and medals with his naval aviator “wings of gold.”

The new naval aviation service also adopted a wing device for their aviators that incorporated a similar design (bird wings attached to a shield with stars and stripes) but with an anchor, arranged vertically, extending from behind the shield with the ring and stock above and the crown and flukes below. Most of these early wings were constructed in a gold metal (sometimes actual gold) or embroidered using gold bullion thread. The navy wings of gold remain virtually unchanged to present day, with variations occurring between various manufacturers.

With a little effort, new collectors can quickly educate themselves as to the nuances of the (World War II to present) coveted, yet relatively affordable, wings. Many of the naval (which include USMC flyers) and air corps/forces wings from WWII can be had for prices ranging from $50-$100 depending on the scarcity or abundance of the variant.

During World War II, women pilots were needed to ferry aircraft from the manufacturers to the troops, saving the experienced aviators for front-line combat. This beautiful WASP uniform features pilot wings.

Due to the incredible desirability and rarity of wings (i.e. extremely high dollar values) from the first World War, these pieces are some of the most copied and faked militaria items. Some of the examples are so well-made (in some cases, by skilled jewelers) that expert collectors have difficulty discerning them from the genuine artifacts. The best advice before acquiring a WWI piece is to consult an expert. Also, be sure that the seller is reputable and will offer a full refund if the item is determined to be a fake.

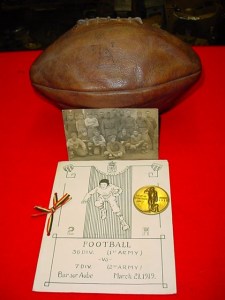

WWI Aero Trophies: Aviation Artifacts of Aero-Warriors

Archaeologists could agree that in some form or fashion, militaria collecting has been around seemingly since men have gone to war. Though the concept may not have been seen as collecting, at a base level, man has maintained combat-related artifacts to remind him of battles won or brothers-in-arms that were lost. Not only has man sought to remember his warring past, he has long maintained the spoils of war by removing specific items of his vanquished opponent’s body as it laid on the field of battle.

This illustration from Tut’s tomb shows the young pharaoh at war in his chariot (source: Araldo De Luca).

When some of the tombs of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs were opened and the contents were inspected and cataloged, among the gilded, religious and life-story items were weapons of war. Free from the worries and troubles of earth, anthropologists and Egyptologists surmised that the military pieces were objects that heralded the deceased king’s victories. Within the tomb of the most widely known pharaoh, King Tutankhamen (or “Tut”), among several depictions of him in combat, was his beautifully ornate chariot that would, more than likely, have been used in battle as documented throughout his burial treasure.

This section of fabric from an aircraft belonging to the famed Lafayette Escadrille (a squadron of American volunteers that flew for France during WWI) recently sold at auction (source: Cowan Auctions).

With the advancement of technology came the modern version of the chariot during World War I, the airplane. The warrior who battled from the seat of these modern machines, though differently equipped, had much in common with the brave Egyptian warriors of ancient times as they bravely piloted their flying machines into the center of the fray. In the quiet of the battle’s aftermath, these warriors would, if possible, descend from their winged chariots to survey their opponent’s wreckage, tearing or cutting strategic pieces of the fabric that contained specific identifying marks that helped to tell their story to both their squadron mates and to their leaders, providing quantifiable evidence of their success.

This section of cloth survives from an aircraft of the 1st Army Aero Pursuit Squadron and is preserved at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.

In many cases, these aerial opponents would extend honors that were reserved for their own fallen heroes, to their vanquished enemies. When Manfred von Richthofen, Rittmeister (Cavalry Captain) of the Luftstreitkräfte (Imperial German Army Air Service) was killed when his Fokker Dr1 was downed, members of the Royal Air Force took custody of his remains. To a casual observer viewing his funeral service, it would have appeared that a renowned British war hero was being laid to rest by the varying honors being rendered to this fallen adversary. However, the preservation of his aircraft was overlooked as souvenir hunters quickly rendered the nearly undamaged plane a shamble as they haphazardly dismantled it.

- A section of fabric from a German WWI aircraft with the letters ‘Fok’ could originate from a Fokker war plane. The colorful pattern was typical of the camouflage painting of the war (source: eBay image).

- Showing what was left of Richthofen’s heavily scavenged wrecked Dr 1.

- The elaborate funeral procession for Manfred von Richthofen.

Bestowing honor upon fallen adversaries was practice by the Allies’ opponents, the Germans. Quentin Roosevelt, son of the former president and colonel (from the Spanish-American War’s Rough Riders), was an aviator in the 95th Aero Squadron, flying pursuit aircraft such as the French-made Nieuport 28. After he was shot down during an engagement, his flight of twelve was jumped by seven German fighter planes. Roosevelt received two fatal bullet wounds to his head and his aircraft rolled over and spiraled to the ground. His subsequent funeral service was witnessed by a fellow American soldier, Captain James E. Gee (110th Infantry) who had earlier been taken prisoner:

“In a hollow square about the open grave were assembled approximately one thousand German soldiers, standing stiffly in regular lines. They were dressed in field gray uniforms, wore steel helmets, and carried rifles. Near the grave was a smashed plane, and beside it was a small group of officers, one of whom was speaking to the men. I did not pass close enough to hear what he was saying; we were prisoners and did have the privilege of lingering, even for such an occasion as this. At the time, I did not know who was being buried, but the guards informed me later. The funeral certainly was elaborate. I was told afterward by Germans that they paid Lieutenant Roosevelt such honor not only because he was a gallant aviator, who died fighting bravely against odds, but because he was the son of Colonel Roosevelt whom they esteemed as one of the greatest Americans.”

Collecting aviation artifacts from WWI is becoming increasingly difficult as nearly a century has elapsed since the armistice was signed. The soft materials that made up the uniforms and accouterments are under continuous attack from the ravages of time and every manner of decay brought on by insects and ultraviolet exposure. Museums in the last few decades have done amazing work at acquiring the best examples of surviving armament and other hardware to provide their audiences with incredible displays and depictions of the Great War. When the rarest pieces arrive in the marketplace, the heavy competition ensues driving the prices skyward.

In an older episode of the History Channel’s Pawn Stars (the “Stick to Your Guns” episode), a woman enters the shop with a rolled-up section of old fabric emblazoned with a hand-painted representation of an American flag. She tells the story of her American serviceman relative darting over to a recently wrecked plane to cut out the flag, saving it from the ensuing fire resulting from the crash.

This flag looks to have been cut from a WWI American aircraft. The jury is still out as to whose aircraft it was removed from (source: Pawn Stars screen grab).

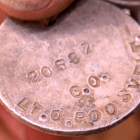

In providing the requested provenance, she presents a pair of World War I dog tags. One of the tags shows the information for her ancestor while the other contains the personal identification of Lieutenant Quentin Roosevelt. The Pawn Stars segment could easily lead viewers to draw the conclusion that the flag was removed from Roosevelt’s wreckage but that would be a considerable leap based upon the story of the retrieval and the burning aircraft. It would have been difficult for American to do so, considering that Roosevelt crashed behind enemy lines.

- Could this dogtag have come from Lt. Quentin Roosevelt? It was attached to another WWI tag belonging to the ancestor of the woman who brought in a hand-painted section of WWI airplane fabric to the Pawn Stars’ pawn shop (source: Pawn Stars screen grab).

- The reverse side of George Pyne’s dog tag shows that he was a member of the 36th Aero Squadron (source: Pawn Stars screen grab).

- WWI dog tag belonging to Private George W. Pyne – who is purported to have cut a section of aircraft fabric from a burning wreck – the fabric contains a hand-painted American flag (source: Pawn Stars screen grab).

Ultimately, the Pawn Stars folks purchased the flag (the price was well into four figures) despite the lack of connection to Roosevelt. In my opinion, they probably overpaid for the piece but considering that it was destined for Gold & Silver Pawn Shop owner Rick Harrison’s personal collection, it wasn’t too much of a reach.

A Thousand Words? Pictures Are Worth so Much More!

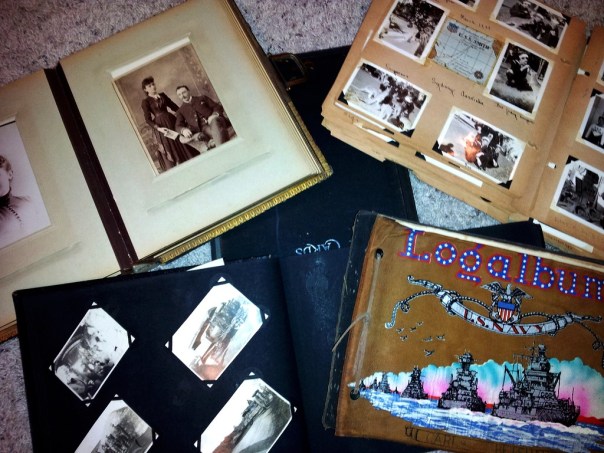

As my family members have passed over the past several years, I have managed to acquire a number of antique photo albums and collections of photos of (or by) my family members that nobody else wanted. Most of the images’ subjects were of family gatherings, portraits or nondescript events and contained a lot of unknown faces of people long since gone. As the only person in the family who “seems to be interested” in this sort of history, I have become the default recipient.

Here is a sampling of vintage photo albums I’ve inherited.

My Hidden Treasure

With all the activities and family functions occurring in my busy life, those albums received a rapid once-over (to see if I could discern any of the faces) and then were shelved to gather dust as they had done with their previous owners. Years later, I began to piece together a narrative of my relatives’ military service (a project you will hear about over the course of my blog posts). I have since returned to those albums only to discover a small treasure of military-related images that are serving to illustrate my narrative project. As an added bonus, they are providing me with an invaluable visual reference as I am reconstructing uniform displays to honor these veterans.

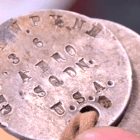

Photographs Can Unlock the Secrets

Similarly, militaria collectors strike gold when they can obtain photo of a veteran in uniform that can help to provide authentication as part of the due diligence for a specific group they are investigating prior to an acquisition. A photo showing the veteran wearing a certain Shoulder Sleeve Insignia (SSI), ribbon configuration or even a specific uniform garment can be authenticated if there are visible traits (such as tears or repairs) within the image.

Photographs from GIs in a wartime theater of operations or in combat are fairly rare. Photography was outlawed by theater commanders (due to the obvious security risks if the film or photographs were captured) and space was at a premium as one had to pack their weapons, ammunition, rations and essential gear. So finding the room to safely carry a camera and film for months at a time was nearly impossible. Similarly, shipboard personnel were not allowed to keep cameras in their personal possessions. Knowing the determination of soldiers, airmen and sailors, rules were meant to be broken and, fortunately for collectors, personal cameras did get used and photos were made while flying under the censors’ radar.

If you have deep pockets and you don’t mind paying a premium for pickers to do the legwork, wartime photo albums can be purchased online (dealers, auction sites) for hundreds of dollars. Many times, this can be a veritable crap-shoot to actually find images that have significant military or historical value and aren’t simply photos of an unnamed soldier partying with pals in a no-name bar in an an unknown location. For militaria collectors at least, there is value in the image details.

As you obtain military-centric photos, take the time to fully examine what can be seen. Don’t get distracted by the principal subject – look for the difficult-to-see details. Purchase a loupe or magnifying glass to enable you discern the traits that can reveal valuable information about when or where the photo was snapped. What unit identifying marks can bee seen on the uniforms? Can you identify anything that would help you to determine the era of the uniforms being worn by the GIs?

My Own Success

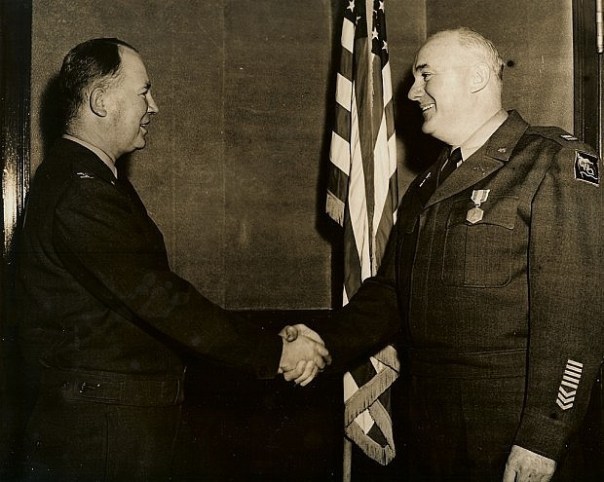

In assembling a display for one of my relatives, I wanted to create an example of his World War I uniform because the first of his three wars was quite significant in shaping his character for his lifetime. Having already obtained his service records (which span his entire military career, concluding a few years after the Korean War), a book that was written about his WWI unit (published by a fellow unit member) and my uncle’s photo album which was filled with snapshots of his deployment to France, I figured I would be able create a decent uniform representation.

- In this image, you can’t quite make out the left shoulder insignia.

- A close-up of the left shoulder revealed the SSI of the 1st Army (artillery branch).

- This photo shows my uncle (on the left) in France with his First Class Gunner rank insignia.

- In the close-up, you can (almost) clearly make out the rank insignia of a First Class Gunner.

An overview of the uniform (and overseas cap) that I have recreated to represent my uncle’s WWI service. Note the artillery shell insignia on the right sleeve is that of a First Class Gunner.

In the various photo album images, I could see his right sleeve rank insignia as well as the overseas stripes on his left sleeve quite clearly. I could even make out his bronze collar service devices or “collar disks” in the photos (since I had his originals, they weren’t in question), but I had no idea of what unit insignia should go on his left shoulder. Not to be denied, I took the route of investigating his unit and the organizational hierarchy, trying to pinpoint the parent unit to which the 63rd Coastal Artillery Corps was assigned. Having located all of that data, I was still unsure of the SSI for the right shoulder.

Temporarily sidetracked from the uniform project, I returned to the photo album and scanned a few of the images (at the highest possible resolution) for use in my narrative. With one of the photos, I began to pay close attention to the left shoulder as I zoomed in tightly to repair 90 years worth of damage…and there it was! At the extreme magnification, I could clearly see the 1st Army patch (with the artillery bars inside the legs of the “A”) on my uncle’s left shoulder. I had missed it during the previous dozens of times that I viewed the photo.

An overview of the uniform (and overseas cap) that I have recreated to represent my uncle’s WWI service. Note the artillery shell insignia on the right sleeve is that of a First Class Gunner.

A close up of the SSI of the 1st Army (with the red and white bars of the artillery), my uncle’s collar disks, the honorable discharge chevron and his actual ribbons.

My research now complete, I obtained the correct vintage patches and affixed them to an un-named vintage WWI uniform jacket along with my uncle’s original ribbons and collar devices (disks) to complete this project. Now I have a fantastic and correct example of my uncle’s WWI uniform to display.