Category Archives: Ephemera and Photographs

Bataan/Corregidor POWs – Looking Back 75 Years

Five months. Depending upon your perspective, this span of time may seem to be a brief moment or a lifetime. If you are anticipating a well-planned vacation, you count the days down with excitement. If you are completing a career and your retirement date is approaching, you might have some anxiety about the significant change in life that you are facing. For the men on Corregidor in May of 1942, it was the culmination of a long-fought battle that was about to come to an end.

The Japanese had planned simultaneous, coordinated attacks on United States military bases in an effort to subjugate American resistance to their dominance in the Western Pacific. Seeking to seize control of natural resources throughout Asia and the South Pacific, the Empire of Japan had already been marching through China, and having invaded Manchuria in 1931, they continued with full-scale war in 1937 as they took Shanghai and Nanking, killing countless thousands during the initial days of hostilities. American sanctions and military forces, although not actively engaged, stood firmly in the Japanese path of dominance.

A copy of the transfer orders for the 5th Air Base Group, October 1941. My uncle’s father is listed here along with one other veteran who was with him throughout his entire stay as a guest of the Empire of Japan.

The father of my uncle (by marriage), enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1941 and was assigned to the Decontamination Unit of the 4th Chemical Company, one of 204 members of the 5th Air Base Group that had been transferred to the in Far East Air Force in the Philippines in late October. Like many other new privates, this man had enlisted to escape the tight grip of the Great Depression and massive unemployment, seeking steady pay while embracing a new life of service to his country. The Philippine Islands, though remote and thousands of miles away from the comforts of home, represented a certain measure of adventure. He was unaware what the next four years would bring.

On December 8, 1942, Japanese forces landed on Luzon in the Philippines as they kicked off what would become a lengthy campaign in an effort to gain control of the strategic location and to remove the threat of any resistance of their ever-expanding empire by the forces of the United States. Grossly under-prepared for war, the 150,000 troops (a combination of American and Philippine forces) were plunged into battle, defending against the onslaught of the 130,000 well-seasoned, battle-hardened enemy forces.

The American forces were almost immediately cut off from the promised supplies and reinforcements that would never be sent.

- 20th Air Force B-29s lined up (on Saipan) for post-surrender POW supply drop.

- An aerial photo (taken by 20th Air Force personnel) of one of the POW camps at Fukuoka.

- As they prepared to resupply them after the surrender of Japan, the 20th Air Force photographed and documented the locations of POW camps throughout Japan.

Over the course of the next five months, U.S. and Philippine forces fought a losing battle in an almost constant state of retreat as supplies wore thin and troops wore out. Exhausted, beat-up and starving, the defenders (of the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor) were done. Having suffered considerable losses (25,000 killed and 21,000 wounded), General Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright indicated surrender by lowering the Stars and Stripes and raising the white flag of surrender. More than 100,000 troops were now prisoners of war in the custody of the Imperial Japanese forces and would endure some of the most inhumane and brutal treatment every foisted upon POWs. My uncle’s father, a young private was now among the captured, on the march to an uncertain future.

An engraved mess kit from a Bataan veteran (photo source: Corregidor – Then and Now).

The five months of uncertainty and hopelessness that my uncle’s father experienced as a Bataan Defender since hostilities began would become years of daily struggles to survive in prison camps where beatings, starvation and executions were the new normal.

A POW letter to loved ones providing basic information of internment (photo source: Corregidor – Then and Now).

To say that Prisoner of War artifacts are a rarity is a gross understatement. POWs (captives of the Japanese) had to scrounge, steal and beg for basic necessities. Any personal possessions they might have had during the 80-mile forced march were taken once they arrived at makeshift camps. Those few captives who were crafty would manage to conceal small mementos, avoiding detection by the prison guards.

Aside from personal accounts of the atrocities that were told by liberated prisoners after the war, documentation proved helpful in war crime trials of the Japanese camp administrators. Prisoners ferreted away scarce paper and documented brutal acts and names of POWs who were killed or died of disease and starvation. Any of the items that were brought home by these men have tremendous significance as historical records and possess value well beyond a price tag.

May 6, 2017 marks the 75th anniversary of the surrender that launched a painful chapter in my uncle’s father’s life that remained with him for the rest of his years. Through my research, I have been able to determine that he was a POW at the Davao Penal Colony until it was closed in August of 1944. By the war’s end, he had been moved to Nagoya #5-B having made the trip to Japan aboard one of the infamous Hell Ships.

He never really talked about his experiences (at least with me). This man chose instead to let the past remain in its proper place. Unfortunately, I don’t know what might have become of any items he may have returned home with. My hope is that if they do exist, his POW artifacts are with his children or grandchildren, preserved in hopes that his experiences are not forgotten.

Bataan Prisoners of War References:

Finding the “Lady Lex,” One Piece at a Time

A few weeks ago, our nation honored the 75th anniversary of the sneak attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7th. In the past few years, we have marked significant anniversaries of victories from WWII, the War of 1812 and this year we will begin recognizing the centennial of the U.S.entrance into the Great War. For collectors, these occasions spur us to evaluate our own collections while attempting to be discerning of sellers’ listings who are also trying to capitalize on the sudden interest.

In May of this year, 75 years will have elapsed since the first significant clash between the opposing naval forces of Japan and the United States in the Coral Sea. Leading up to this battle, the Navy had suffered losses in The Philippines, Wake Island and Guam followed by the sinking of the USS Houston (in the battle of Sunda Strait) all of which were leaving the U.S. extremely vulnerable and nearly incapable of mounting a naval offensive.

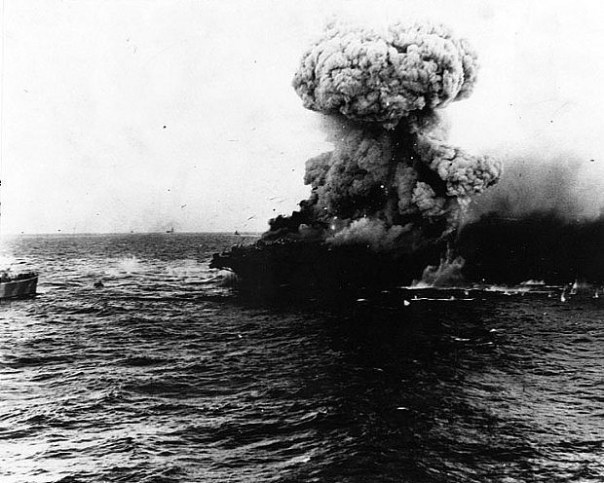

The Lady Lex is rocked by an enormous explosion during the Coral Sea battle, May 8, 1942 (Photo: Naval Historical Center).

USS Lexington (CV-2) provides electrical power to the City of Tacoma (WA) during a severe drought and subsequent electricity shortage – December 1929 – January 1930 (Photo: Tacoma Public Library).

Beginning with a joint effort between the US Army Air Force and the US Navy, the fight was taken to the Japanese home front with an B-25 air strike launched from the USS Hornet. But the direction of the war was seriously in doubt and Navy brass knew that inevitably, a direct naval engagement with the Japanese fleet were very near on the horizon.

Navy code-breakers had discovered the Imperial Japanese forces intended on taking Port Moresby in New Guinea and quickly dispatched Task Forces (TF) 11 and 17 to join up with TF 44 near the Solomon Islands and proceed West toward the Coral Sea. Over the course of May 3rd through 8th, the ensuing engagements between US and IJN forces resulted in substantial losses for both sides, including a carrier from each navy.

For the U.S. Navy, that carrier was the USS Lexington, CV-2. Though not the first purpose-built aircraft carrier (that distinction goes to the USS Ranger CV-4), Lexington was the first to be originally commissioned as a flat top. The Langley (CV-1) had a previous life as a collier, the USS Jupiter, for seven years from 1913 to 1920. The “Lady Lex”, as she would come to be known, laid down as a battle cruiser but was reconfigured during construction and was commissioned in 1927 as the US Navy’s second carrier, CV-2.

The result of the Coral Sea Battle was that the Navy was left with just two operational carrier: Hornet and Enterprise, as the Yorktown also suffered substantial damage in the battle requiring repairs. Less than a month later, the tables would be turned on Japan with the major American victory at Midway.

- A postal cover of the USS Lexington (Photo: Navsource.org).

- A leather squadron patch from the Early Knights of Bombing Two (VB-2) from the Lexington (photo: Brian’s WWII Surplus& Antiques Store)

- This SBD-2 Dauntless aircraft was recovered from a lake where it sat since 1945. While it was not a veteran of the Coral Sea battle, it did fly from the decks of the Lexington during the early months of 1942 (photo: National Naval Aviation Museum)

- This plotting board was used by Lieutenant (junior grade) Joseph Smith during the Battle of the Coral Sea when, while on a scouting mission from the carrier Lexington (CV 2), he spotted Japanese aircraft carriers and their escorts (photo: Naval Aviation Museum).

- A sailor’s leather-bound USS Lexington CV-2 Photo album (photo: eBay).

The loss was not only felt by her crew and navy strategists, but also by communities, such as Tacoma, Washington. For 31 days during winter drought conditions, the Lexington was sent to aid the city’s citizens by generating power ’round the clock, helping to keep their homes lit and warm. Many of those beneficiaries of the electrical power assistance were devastated by the news of her loss.

Today, few artifacts remain from the Lady Lex. Militaria collectors would be hard-pressed to obtain anything specific to the ship, instead having to settle for obtaining USS Lexington veterans’ personal effects or uniform items, surviving ephemera, philatelics, or vintage photographs. For many naval collectors, the hunt for anything from this historic ship can very rewarding. Some artifacts can be found by happenstance as was the case with this Curtiss SB2C Hell Diver, recently pulled from the Lower Otay Reservoir near San Diego, discovered by a fisherman who observed the plane’s outline on his fish-finder.

Armed with patience and time, collectors could assemble a nice group of artifacts to pay proper respect to the Lady Lex and the men who served aboard this historic ship.

UPDATE March 5, 2018: Paul Allen’s Undersea Exploration team that has been searching and discovering the wrecks of the Pacific War, finding such infamous sunken vessels as the USS Indianapolis and the lost ships from the Battle of Savo Island (USS Vincennes, Astoria and HMAS Canberra), announced today that they have located and filmed the wreck of the USS Lexington (CV-2) at the bottom of the Coral Sea in nearly two-miles of depth.

A Thousand Words? Pictures Are Worth so Much More!

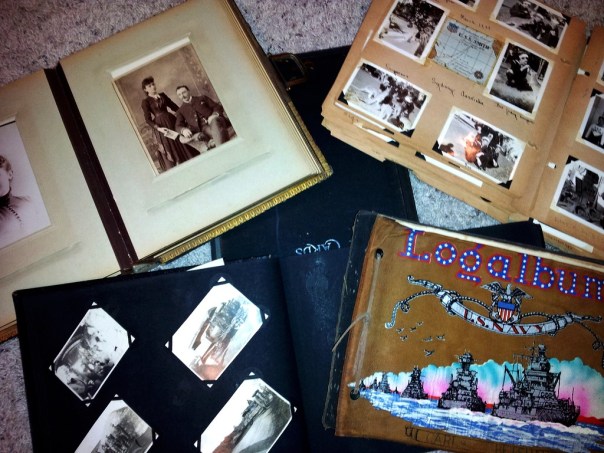

As my family members have passed over the past several years, I have managed to acquire a number of antique photo albums and collections of photos of (or by) my family members that nobody else wanted. Most of the images’ subjects were of family gatherings, portraits or nondescript events and contained a lot of unknown faces of people long since gone. As the only person in the family who “seems to be interested” in this sort of history, I have become the default recipient.

Here is a sampling of vintage photo albums I’ve inherited.

My Hidden Treasure

With all the activities and family functions occurring in my busy life, those albums received a rapid once-over (to see if I could discern any of the faces) and then were shelved to gather dust as they had done with their previous owners. Years later, I began to piece together a narrative of my relatives’ military service (a project you will hear about over the course of my blog posts). I have since returned to those albums only to discover a small treasure of military-related images that are serving to illustrate my narrative project. As an added bonus, they are providing me with an invaluable visual reference as I am reconstructing uniform displays to honor these veterans.

Photographs Can Unlock the Secrets

Similarly, militaria collectors strike gold when they can obtain photo of a veteran in uniform that can help to provide authentication as part of the due diligence for a specific group they are investigating prior to an acquisition. A photo showing the veteran wearing a certain Shoulder Sleeve Insignia (SSI), ribbon configuration or even a specific uniform garment can be authenticated if there are visible traits (such as tears or repairs) within the image.

Photographs from GIs in a wartime theater of operations or in combat are fairly rare. Photography was outlawed by theater commanders (due to the obvious security risks if the film or photographs were captured) and space was at a premium as one had to pack their weapons, ammunition, rations and essential gear. So finding the room to safely carry a camera and film for months at a time was nearly impossible. Similarly, shipboard personnel were not allowed to keep cameras in their personal possessions. Knowing the determination of soldiers, airmen and sailors, rules were meant to be broken and, fortunately for collectors, personal cameras did get used and photos were made while flying under the censors’ radar.

If you have deep pockets and you don’t mind paying a premium for pickers to do the legwork, wartime photo albums can be purchased online (dealers, auction sites) for hundreds of dollars. Many times, this can be a veritable crap-shoot to actually find images that have significant military or historical value and aren’t simply photos of an unnamed soldier partying with pals in a no-name bar in an an unknown location. For militaria collectors at least, there is value in the image details.

As you obtain military-centric photos, take the time to fully examine what can be seen. Don’t get distracted by the principal subject – look for the difficult-to-see details. Purchase a loupe or magnifying glass to enable you discern the traits that can reveal valuable information about when or where the photo was snapped. What unit identifying marks can bee seen on the uniforms? Can you identify anything that would help you to determine the era of the uniforms being worn by the GIs?

My Own Success

In assembling a display for one of my relatives, I wanted to create an example of his World War I uniform because the first of his three wars was quite significant in shaping his character for his lifetime. Having already obtained his service records (which span his entire military career, concluding a few years after the Korean War), a book that was written about his WWI unit (published by a fellow unit member) and my uncle’s photo album which was filled with snapshots of his deployment to France, I figured I would be able create a decent uniform representation.

- In this image, you can’t quite make out the left shoulder insignia.

- A close-up of the left shoulder revealed the SSI of the 1st Army (artillery branch).

- This photo shows my uncle (on the left) in France with his First Class Gunner rank insignia.

- In the close-up, you can (almost) clearly make out the rank insignia of a First Class Gunner.

An overview of the uniform (and overseas cap) that I have recreated to represent my uncle’s WWI service. Note the artillery shell insignia on the right sleeve is that of a First Class Gunner.

In the various photo album images, I could see his right sleeve rank insignia as well as the overseas stripes on his left sleeve quite clearly. I could even make out his bronze collar service devices or “collar disks” in the photos (since I had his originals, they weren’t in question), but I had no idea of what unit insignia should go on his left shoulder. Not to be denied, I took the route of investigating his unit and the organizational hierarchy, trying to pinpoint the parent unit to which the 63rd Coastal Artillery Corps was assigned. Having located all of that data, I was still unsure of the SSI for the right shoulder.

Temporarily sidetracked from the uniform project, I returned to the photo album and scanned a few of the images (at the highest possible resolution) for use in my narrative. With one of the photos, I began to pay close attention to the left shoulder as I zoomed in tightly to repair 90 years worth of damage…and there it was! At the extreme magnification, I could clearly see the 1st Army patch (with the artillery bars inside the legs of the “A”) on my uncle’s left shoulder. I had missed it during the previous dozens of times that I viewed the photo.

An overview of the uniform (and overseas cap) that I have recreated to represent my uncle’s WWI service. Note the artillery shell insignia on the right sleeve is that of a First Class Gunner.

A close up of the SSI of the 1st Army (with the red and white bars of the artillery), my uncle’s collar disks, the honorable discharge chevron and his actual ribbons.

My research now complete, I obtained the correct vintage patches and affixed them to an un-named vintage WWI uniform jacket along with my uncle’s original ribbons and collar devices (disks) to complete this project. Now I have a fantastic and correct example of my uncle’s WWI uniform to display.

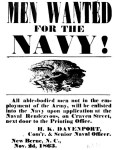

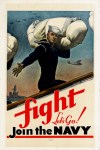

Drawing in Recruits: Posters and Broadsides

Tonight, as I was finishing up some research for one of my genealogy projects, I found myself clicking through a series of online auction listings of militaria that would look absolutely fantastic hanging on the walls of my “war room.” My mind began to wander with each page view, imagining the various patriotic renderings, designed to inspire the 1940s youth to rush to their local recruiter to almost single-handedly take on the powers of the Axis nations.

Originally created for Ladies Weekly in 1916, the iconic image of Uncle Sam was incorporated into what is probably the single, most popular recruiting poster that began its run during WWI (source: Library of Congress).

Rather than focusing on the raging war in Europe, this Charles Ruttan-designed poster demonstrates the career and travel opportunities.

Recruiting posters are some of the most collected items of militaria as their imagery conjures incredible emotional responses, such as intense national sentiment, inflamed hatred of the new-found enemy or a sense of call of duty. The colorful imagery of these posters inspires considerable interest from a wide range of collectors, in some cases driving prices well into four-digit realms.

Most Americans are familiar with the iconic imagery of Uncle Sam’s “I Want YOU for the U.S. Army” that was created and used in the poster by James Montgomery Flagg, making its first appearance in 1916, prior to the United States’ entry into World War I. While this poster is arguably the most recognizable recruiting poster, it was clearly not the first. Determining the first American use of recruiting posters, one need not look any further than the Revolutionary war with the use of broadsides, one of the most common media formats of the time.

The use of broadsides, some with a smattering of artwork, continued to be utilized well into (and beyond) the Civil War with both the Army and Navy seeking volunteers to fill their ranks. With the advancement of printing technology and the ability to incorporate full color, the artwork began to improve, adding a new twist to the posters, providing considerable visual appeal. By the turn of the twentieth century, well-known artists were commissioned to provide designs that would evoke the response to the geopolitical and military needs of the day.

- Known as a broadside, this poster mentioned that able-bodied men that were not headed for Army ranks would be enlisted into Naval service.

- This is a beautiful example of a Revolutionary War broadside is recruiting soldiers for service in General Washington’s Army for Liberties and Service in the United States (source: ConnecticutHistory.org).

Adding to the appeal for many non-militaria collectors is artist cache associated with many of the recruiting poster source illustrations. The military brought in the “big guns” of the advertising industry’s graphic design, tapping into the reservoir of well-known artists; if their names weren’t known, their stylings had permeated into pop culture by way of ephemera and other print media advertising. In addition to James Flagg, some of the most significant (i.e. most sought-after and most valuable) Navy recruiting posters were designed by notable artists such as:

- Howard Chandler Christy’s famous “Christy Girl” poster from World War I.

- This sailor extends his hand to would-be recruits encouraging them to climb aboard and join the fight. McClelland Barclay incorporated his advertising industry experience in graphic-design and style into these recruiting posters.

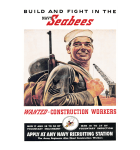

- The Naval Construction Battalion (CB or “Sea Bees”) was proposed in 1941 and established immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack. This poster (illustrated by John Falter) was used to attract journeymen construction tradesmen who would build all of the bases and airfields used to push the Japanese back to their homeland, one island at a time.

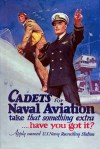

- Another McClelland Barclay poster showing a naval aviator climbing into his open-cockpit aircraft with a battleship mast and superstructure showing in the background.

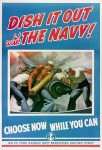

- These sailors rapidly load the naval gun as they are actively engaged in combat. This imagery (by McClelland Barclay) was designed to fan the flames of nationalism and nudge those seeking to avenge the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Sadly, with my limited budget and my unwillingness to horse-trade any of my collection, these posters are somewhat out of my reach. It goes without saying that condition and age along with desirability have direct impact on value and selling prices. Some of the most desirable posters of World War II can sell for as much as $1,500-$2,000. For the collector with deeper pockets, Civil War broadsides can be had for $4,500-$6,000 when they become available. I have yet to locate any of the recruiting ephemera from the Revolutionary War, so I wouldn’t begin to speculate the price ranges should a piece come to market.

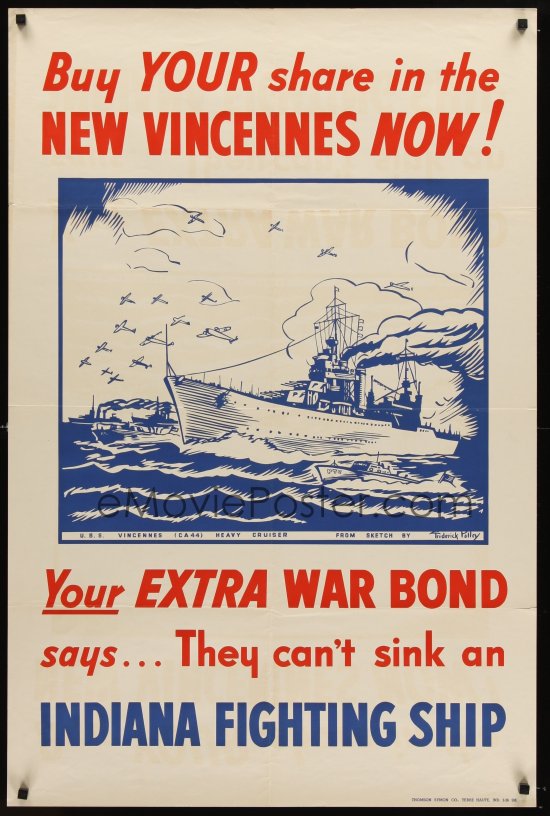

The citizens of a small Indiana town (Vincennes) raised enough money through a successful bond drive to meet the Secretary of the Navy’s financial requirement which resulted in the already under construction light cruiser (CL-64) to be named Vincennes.

Discouraged as I may be in my quest to secure one of these treasured prints, I may be better off seeking quality reproductions to adorn the vertical white-space of my war room. However, a few years ago I received a reproduced war-bond drive poster – the original was created to encourage Hoosiers to buy bonds to name a new cruiser to honor the (then) recently sunk USS Vincennes.

Note: All images not sourced are provided courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command

Calculated Risks: Bidding on Online Auctions that Contain Errors

Regardless of how much knowledge you may possess, making good decisions about purchasing something that is “collectible” can be a risky venture ending in disappointment and being taken by, at worst, con-artists or at best, a seller who is wholly ignorant of the item they are selling. Research and gut-instinct should always guide your purchases for militaria. Being armed with the concept that when something is too-good-to-be-true, it is best to avoid it. I recently fell victim to my own foolishness when I saw an online auction listing for an item that was entirely in keeping with what I collect.

I am very interested in some specific areas of American naval history and one of my collecting focus centers around a select-few ships and almost anything (or anyone) who might have been associated with them. One of those ships (really, four: all named to honor the Revolutionary War battle where American George Rogers Clark was victorious in Vincennes, IN), the heavy cruiser USS Vincennes (CA-44) is one in particular that I am constantly on the lookout for.

- The auction listing is innocuous; albeit accurate. However, the details are where this seller’s words are misleading and troublesome.

- Note in the description that the seller lists specifics about the book (nothing the title, author and edition). Sadly, this is a farse.

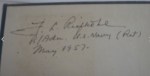

- There were two factors that led me to purchase this book: Admrial Riefkohl’s signaturem that it was in, what I consider to be one of the most accurate accounts of the Savo Island battle.

In early September (2016), a listing for an item that surfaced in one of my saved searches results, caught my attention on eBay. The auction description made mention of a book, Savo: The incredible Naval Debacle Off Guadalcanal, that happens to be one of the principle, reliable sources for countless subsequent publications discussing the August 8-9, 1942 battle in the waters surrounding Savo Island. Though I read this book (it was in our ship’s library) years ago, it is a book that I wanted to add to my collection but until this point, never found a copy that I wanted to purchase. What made this auction more enticing was that this book featured a notable autograph on the inside cover. In viewing the seller’s photos, I noted that the dust jacket was in rough shape but the book appeared to be in good condition (though the cover and binding were not displayed). There were no bids and the starting price was less than $9.00.

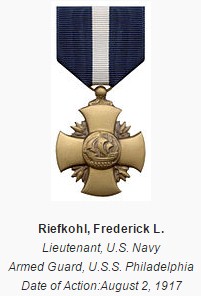

Riefkohl was awarded the Navy Cross medal for actions performed aboard the USS Philadelphia against German submarines during WWI convoy escort operations (see the test of the accompanying citation below).

I have been a collector of autographs and have obtained several directly from cultural icons (sports stars, actors, musicians) but my favorites are of notable military figures (recipients of the Medal of Honor [MOH] and other servicemen and women) who distinguished themselves in service to our country. The signature in this book featured a retired naval officer who was the recipient of the Navy’s highest honor, the Navy Cross (surpassed only by the MOH) and who played a significant role in the Battle of Savo Island as he was the commanding officer of the heavy cruiser, USS Vincennes (CA-44) and the senior officer present afloat (SOPA) for the allied group of ships charged with defending the northern approaches (to Savo and Tulagi islands). Frederick Lois Riefkohl (then a captain) commanded the northern group which consisted of four heavy cruisers; (including Vincennes) USS Quincy (CA-39), Astoria (CA-34) and HMAS Canberra (D33).

By all accounts, the Battle of Savo Island (as the engagement is known as) is thought to be one of the worst losses in U.S. naval history (perhaps second only to the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor) as within minutes of the opening salvos by the Japanese naval force, all four allied ships were left completely disabled and sinking (all would succumb to the damage and slip beneath the waves in the following hours). Though the loss was substantial, the Japanese turned away from their intended targets (the allied amphibious transport ships that were landing marines and supplies on Guadalcanal and Tulagi) missing a massive opportunity to stop the beginnings of the allied island-hopping campaign. The First Marine division was permanently entrenched on these islands, and would drive the Japanese from the Solomons in the coming months.

Captain Frederick Lois Riefkohl (shown here as a rear admiral).

Captain Riefkohl was promoted to Rear Admiral and retired from the Navy in 1947 having served for more than 36 years. He commanded both the USS Corry (DD-334) and the Vincennes and having served his country with distinction, the Savo Island loss somewhat marred his highly successful career.

As I inspected the book, there were a few aspects that gave me reason for pause. First, the seller described the book as “SAVO by Newcomb 1957 edition” which left me puzzled. Secondly, the Admiral included a date (“May 1957”) with his signature. Recalling that Newcomb’s book was published in 1961 ( See: Newcomb, Richard Fairchild. 1961. Savo. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.), I was a bit dismayed by the four-year discrepancy between the date of the autograph and (what the seller determined to be the) first edition published date. I wondered, “how did he determine this date and where did he find this information?” I noted that there was no photograph of the book’s title page accompanying the auction.

I decided to take a gamble that at worst, would result in me spending a small sum of money for an autograph that I wanted for my collection and at best was merely a fouled up listing by an uninformed seller. I pulled the trigger and my winning bid of $8.99 had the book en route (with free shipping, to boot)!

The dust jacket is in very rough shape with tears, creases, cracks, shelf wear and dog-ears. The cover art is fairly intense in conveying what took place in the battle.

The confirmation that I didn’t want; this book turned out to be”Death of a Navy” which isn’t worth investing time to read as it is known to be a rather erroneous work.

Nearly two weeks later, the package arrived. I reservedly opened the packaging and freed the book from the layers of plastic and bubble wrap. I inspected the ragged dust jacket and removed it to see the very clean cover which didn’t seem to match. I opened the book and viewed Riefkohl’s autograph which appeared to match the examples that I have seen previously. I turned to the title page and confirmed my suspicions. Death of a Navy by an obscure French author, Andrieu D’Albas (Captain, French Navy Reserve). “Death” is not worthy enough to be considered a footnote in the retelling of the Pacific Theater war as D’ Albas’ work is filled with errors. By 1957 (when this book was published), most of what was to be discovered (following the 1945 surrender) from the Japanese naval perspective was well publicized before the start of the Korean War. It is no wonder why Andrieu D’Albas published only one book.

- Death of a listing. This acquisition turned out to be a partial dud.

- Removing the dust jacket, the cover didn’t seem to match the dust jacket.

My worst-case scenario realized, I now (merely) have the autograph of a notable U.S. naval hero in my collection. While I could have gone with my gut feelings about the auction listing, having this autograph does offset my feelings of being misled (regardless of the seller’s intentions).

Admiral Riefkohl’s signature appears to be authentic leaving me semi satisfied in that I obtained a great autograph for my collection.

Riefkohl’s Navy Cross Citation:

The Navy Cross is awarded to Lieutenant Frederick L. Riefkohl, U.S. Navy, for distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commander of the Armed Guard of the U.S.S. Philadelphia, and in an engagement with an enemy submarine. On August 2, 1917, a periscope was sighted, and then a torpedo passed under the stern of the ship. A shot was fired, which struck close to the submarine, which then disappeared