Where does the time go? I know that my writing schedule has been severely impacted by home and work priorities (this column is nowhere near being a day job for me) and other facets of life routinely draw my attention away from my love of military history. However, my interest never truly wanes or strays very far from this passion and yet when I checked to see that my last posting was more than three months ago, I realized that I need to get back on the horse and get the creative juices stirred.

I can’t blame writer’s block or submit any grandiose excuses for not writing. I merely de-prioritized my militaria collecting during the 90-day time span. Though my acquisition pace has slowed during the last half-year, I only suggest that I’ve become hyper selective about what I add to the expanding pile. With the smattering of pieces coming through the door, I found myself asking the question, “what should I write about?”

Not wanting to overload the Veteran’s Collection with an overwhelming theme, I have been putting forth an effort to balance the various subjects. My best efforts aside, I find that my posts are skewed toward the Navy (where I served) with some of those topics focusing on a specific ship. Regardless, after a few moments of careful consideration, I decided that instead of talking about a new (to my collection) piece, I would spend some time with something that eluded me a few years ago (the subject just happens to be in a few of my wheelhouses). Missing out on this piece has haunted me since the online auction bidding surpassed my meager budget.

Without going into detail as to what fuels my interests (read my About page for those details), I’ll jump right into today’s topic.

I can bet that half of those who read this column (all four of you) are familiar with the widely popular PBS television production, Antiques Roadshow and have viewed episodes where 19th century maritime folk art objects have been viewed and appraised. One of the most popular types of that particular folk art is scrimshawed marine mammal bones (or teeth/tusks). Needless to say that along with popularity (and scarcity) of these pieces comes an array of reproductions and outright fakes onto the market. Applying the caution of a mariner skirting the shoal waters, one needs to be very knowledgeable before navigating into these waters.

The ship design in the center is clearly that of an 1820s United States Navy sloop of war (source: eBay image).

When this item was listed in an online auction, I was shocked that it lasted without being taken down by the host as genuine scrimshaw violates their established policies that forbid the sale of items made from protected animals. In reading the seller’s description, I noted that it was being sold as a piece that was manufactured from man-made materials rather than from a whale bone or tooth. However, in examining the photos of the piece, it was clearly NOT sourced from synthetics, though I couldn’t be certain without a hands-on inspection. Hoping to get clarification from the seller, I resorted to asking specific questions only to be rebuffed with a message that reiterated the details in the listing’s description.

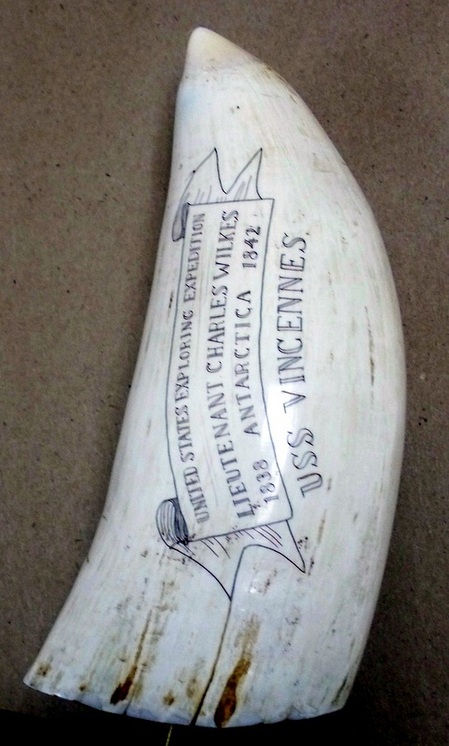

The inscription reads, “United States Exploring Expedition, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, 1838 | Antarctica | 1842. USS Vincennes” (source: eBay image).

The subject of the scrimshaw artwork is what drew me to the piece from the beginning. The illustrations on either side of the “whale tooth” were made to commemorate the United States very first foray into global exploration. The U.S. Exploring Expedition was led by the US Navy’s polarizing figure (of that era), LT Charles Wilkes from 1838-1842 and consisted of men from several biological and geological scientific disciplines along with illustrators, geographical surveyors and naval officers and men aboard six US Navy vessels – the flagship being the sloop of war, USS Vincennes.

On one side of the tooth is a rather elaborate design of the three-masted sloop (a port-side view) that is centered among an array of flags with an eagle perched above an American-themed shield holding arrows and an olive branch which is very reminiscent of 19th century designs. On the reverse is an unrolled scroll that appears to be a banner with the US Ex. Ex, Wilkes’ name, the dates and “Antarctica” emblazoned across. Immediately beneath the scroll is the name of the expedition’s flagship, “USS Vincennes.”

I grappled with deciding to bid on the object. There was no definitive manner in which to determine the authenticity or if it was, in fact, a mocked up piece of plastic. I was left to weigh all of the evidence and draw conclusions (aside from the fact that the seller stated that it wasn’t the real thing which could easily be that person’s subverting of the online auction site’s rules).

An example of an 19th Century whale’s tooth scrimshaw depicting the USS Brooklyn (source: dukeriley.info)

Showing a vintage whale’s tooth scrimshaw mounted to a cork base. Note the similar themes (to the USS Vincennes tooth) and the odd number of stripes on the shield (source: Wikimedia).

The cons

- The tooth is very bright for an early 19th century piece. Most scrimshawed items tend to yellow with time. After 170 years, the bone/tooth material should be much darker.

- Taking a look at the artwork design, what gave me reason to pause is that the artist departed from the widely used American themes within his design. The eagle’s shield is lacking the correct number of stars and stripes (shown are three and 11, respectively).

- The wooden base (which appears to be of dark walnut) that the tooth is mounted to seems to be fairly modern; almost new, conditionally.

This early 19th century flag depicts the three-starred shield and 9 stripes yet the eagle faces his right shoulder (source: NAVA).

The pros

- As someone who, for the last two decades, has been searching for anything pertaining to any of the US Navy warships that bore the same name, this is the only scrimshaw that I have encountered that had any reference to the ship or the expedition. Uniqueness is definitely a plus in that if someone was going to bother manufacturing fakes of this nature, there would, most-likely be multiple examples appearing on the market.

- The cons that I listed above can be explained. The artist may not be as detail-oriented when it comes to the thirteen stars and stripes. However, the direction that the eagle’s head faces is accurate for the time (facing its left shoulder). The illustration of the ship is very accurate to that of the 1820s U.S. sloop of war (designed by Samuel Humphreys) which leads me to believe that the artwork is correct to the period.

- The base could have been merely a replacement or an addition by a subsequent owner.

- The piece may have been stored in a cool, dark location for most of its existence, which could possibly account for the lack of typical aging effects.

The walnut base appears to be a fairly recent addition as it shows no signs of aging (source: eBay image).

After several days of careful consideration, I decided that it was worth a nominal investment risk and configured my bid snipe program accordingly. Within a few hours of the auction close, the bidding (from multiple parties) surpassed my maximum and I watched this beautiful piece of scrimshaw slip into someone else’s hands for several hundred dollars above my limit. It seems that other collectors had arrived at the same conclusion that I had and the benefit of owning such a nice piece far exceeded the risk that it might not be authentic.

For me, this whale tooth was not to be.