Author Archives: VetCollector

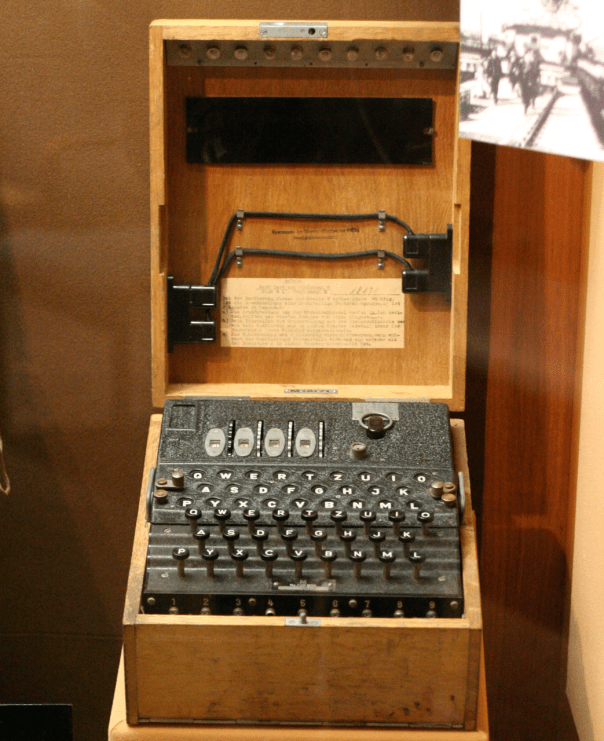

The Enigmatic pursuit of the Third Reich Encryption Machine

History is continuously subjected to revision as stories are told and retold. Researchers and historical experts are seemingly discovering previously hidden facts or secrets that shed new light on events. With the new revelations, previous facts surrounding historical events are skewed or changed causing a re-shaping of timelines and ultimately public perception. Hollywood however, seems bent on taking a different tack with regards to revising history in order to reshape producers’, directors’ and actors’ bank accounts.

This scene shows the disguised American sub (“S-33”) meeting with the U-571 in a rouse to obtain the Enigma code machine (source: Universal Pictures).

In April of 2000, Universal Pictures released a highly successful historical-fiction movie depicting the U.S. Navy’s successful capture of a Kriegsmarine u-boat during World War II. The premise of the film was centered on seizing the keystone encryption device (often referred to as Germany’s “secret weapon”), the Enigma encode/decoding machine along with the codes. While director Jonathan Mostow (who also co-wrote the screenplay) navigates around the historical truths by conveniently mentioning that the story is a compilation of actual events rather than being based on a true story. While this may have worked for American audiences, Great Britain’s Prime Minister (at the time of the film’s release), Tony Blair agreed with discussion (about the film) in Parliament that the story was an affront to the British sailors who gave their lives in the actual retrieval of the Enigma device during the war.

Rather than embarking on a mission to demonstrate the challenges created by Hollywood’s propensity of altering reality (albeit for entertainment purposes), I want to focus more on the capture of the machine and codes and what that meant for achieving an Allied victory over the Axis powers during World War II.

Prior to the United States’ entry into WWII on December 8, 1941, Europe had already been gripped with conflict for twenty-five months. Though it was a highly protected secret, the Allies were fully aware of the existence of the Enigma machine and had already seen successful code-breaking efforts (by the Polish Cipher Bureau in July of 1939) until continued German technological advances rendered those efforts obsolete. It wasn’t until May 9th, 1941 that the Allies achieved their most substantial breakthrough with the British capture of U-110 along with codes and other intelligence materials.

One of the events that is allegedly covered (by the U-571 film) is the United States’ capture of the U-505 in 1944 (three years after U-110) which was towed to Bermuda. Following the war, the U-boat was towed to Portsmouth Navy Yard, New Hampshire where she sat until being transported to Chicago to be displayed as a museum ship. The U-505 is now preserved inside the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Also on display are two Enigma code machines.

In addition to the two machines in the Chicago MOSI, there are a handful in museum collections around the globe. Due to the scarcity of the devices, their notoriety and the impact of their capture had on the outcome of the war, Enigmas command incredible premiums when they surface on the market. As recent as 2011, a Christies’ listing yielded a sale with the winning bid in excess of $200,000.

This Enigma’s selling price was in excess of $35,000 (US) when it was listed at auction in March of 2013 (source: eBay image).

Most recently, the winning bid for an online auction listing (for a three-disk Enigma) seemed to reflect a more modest price as it sold for “only” $35,103. One has to wonder why, in only two years, would there be such a considerable price disparity (obviously factoring model, variant, condition, etc.) between the two transactions. Perhaps the current state of the economy is at play? Maybe the collector or museum with deep pockets was eliminated from the market with their purchase in 2011? Perhaps the $200k selling price was an anomaly and this recent auction reflects a more realistic value?

Either way, the Enigma will remain…well…just that…an enigma with regards to my own collection and the possibility of ever possessing one.

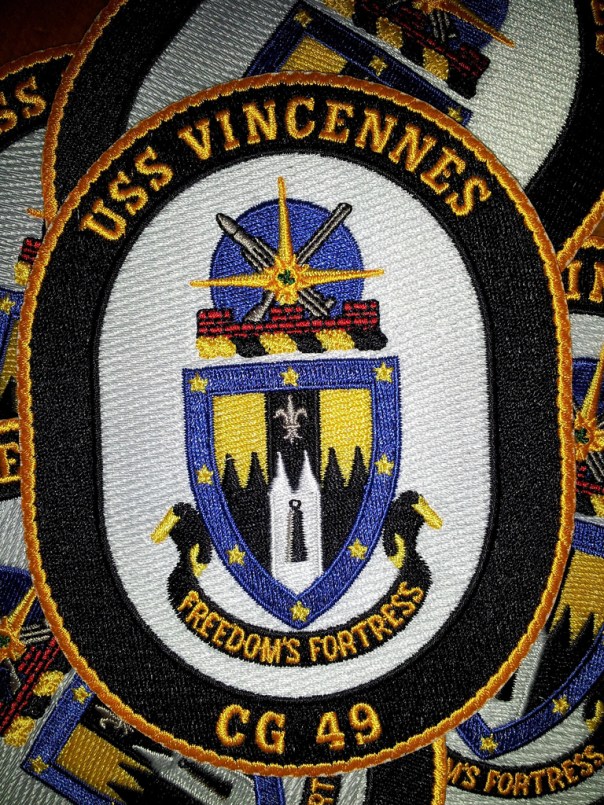

USS Vincennes Under the Microscope

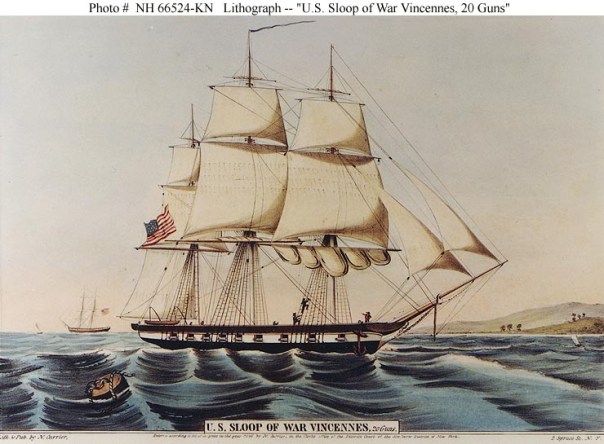

Those who know me on a personal basis understand my affinity for a specific U.S. naval warship. Technically speaking, that interest lies with four combatant vessels, all of which were named to honor the site of a Revolutionary War battle (more accurately, a campaign) that ended the British assaults on the remote Western colonial front. That location in present-day Southwestern Indiana would later become the seat of the Northwest Territorial government in the town of Vincennes.

Colored lithograph published by N. Currier, 2 Spruce Street, New York City, 1845 (source: Naval Historical Center).

My connection to this ship’s name extends all the way back to the place of my birth which was also the location of the commencement of an extensive 1840 charting survey of Puget Sound (in Washington State). Locations and geographical features surrounding my home were named by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (commander of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842) and members of his team when the sloop of war, USS Vincennes (along with other ships of the expedition) was in the Sound. I can even cite some Baconesque connections with great, great, great-grandfather who served in the Ringgold Light Infantry (after he was discharged from his cavalry regiment following a disabling injury). The Ringgold name was inherited from Samuel Ringgold, Expedition-member Cadwalader’s older brother (yes, I realize that this is very convoluted).

My personal connection (to the ships named Vincennes) was solidly established when I was assigned to the pre-commissioning crew of the CG-49. During the first several months (leading toward the 1985 commissioning date), like many of my shipmates, I was exposed to the history of the ship’s namesake and established personal relationships with veterans of the WWII cruisers of the same name. Collecting items from “my” ship was purely functional in that I was proud to purchase t-shirts, lighters, ball caps and other items (from the ship’s store) that bore the name or the image of the ship’s crest. Many of the items I purchased in those days proudly remain in my collection while a few did manage to fade away.

I am constantly on the lookout for artifacts that are connected to these ships (the heavy cruiser: CA-44, the light cruiser: CL-64) and occasionally, some quality pieces (beyond the plethora of typical postal covers) surface on the market. Fortunately, I have been successful in obtaining a few of these items, though the competition has been fierce. The ones that got away were quite stunning.

William D. Brackenridge was the assistant botanist for the U.S. Exploring Expedition serving aboard the USS Vincennes from 1838-1842.

The infrequency of appearances of pieces from the two WWII cruisers pales in comparison to anything related to the 19th Century sloop-of-war. During the past decade of searching for anything related to the USS Vincennes, I have only seen one item connected to the three-masted warship. While searching a popular online auction site, a rather ordinary, non-military item showed up in the search results of one of my automated inquiries. The piece, a wood-cased field microscope from 1830-1840, bore an inscription that connected it to the assistant botanist of the United States Exploring Expedition, William Dunlop Brackenridge.

Admittedly, I am not in the least bit interested in a field microscope as militaria collector, but the prospect of owning such a magnificent piece that would have been a fundamentally important tool used during the United States first foray into exploration was an exhilarating thought. At its core, the goal of the (1838-1842) U.S. Ex. Ex. was to chart unknown waters, seek the existence of an Antarctic continent and discover and document unknown species of flora and fauna. Brackenridge’s field microscope would have been a heavily used item as he and his assistants would most-certainly examine the various characteristics of plant species at a microscopic level.

The box appears to be missing some of the securing hardware which would help to hold the lid closed (source: eBay image).

Authenticity and provenance is certainly a major concern when purchasing a piece like this and the listing made no mention of any materials or means to verify the claim. However, in searching for similar microscopes, there was sufficient comparative evidence to support the time-frame in which the Brackenridge instrument was made. The box and the engraving seems to be genuinely aged and appears to resemble what one would find from a 170 year old example.

The box for the field microscope is inscribed with “Property of W. D. Brackenridge U.S.S Vincennes 1840″(source: eBay image).

In my opinion, the investment was well-worth the risk and I was poised to make my maximum bid (invariably draining my discretionary savings) knowing that the closing price would exceed what I could ultimately afford. The auction closed with the winning bid ($810.58) exceeding my funds by a few hundred dollars, though I suspect that the winner had a far higher bid in place to guarantee victory.

I am a realist yet remain hopeful that I won’t have to wait another decade before another sloop-of-war piece comes to market.

Ancestral Flag: A “Guidon” my Family History

Housed at the US Army Heritage Education Center (located in Carlisle, PA), this image shows one of the actual lances carried by 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry troops.

Years ago, I embarked on a project to document most (if not all) the members of my family’s ancestry who served in the United States armed forces. Researching genealogy can be quite a daunting task when pursuing such a specific theme within confines of a family history. The difficulty in that task is compounded when the there is little or no documentation available to begin with.

I began my research with the names that I knew on my list – my father, grandfather (only one served), uncles, grand uncles and so on. Merely working backwards two generations, I accounted for six veterans (five with combat experience). The third generation up is where I began to experience challenges (some parts of the family emigrated from Canada or the United Kingdom which adds another complexity layer to the research effort), but was able to persevere, discovering several more U.S. service members.

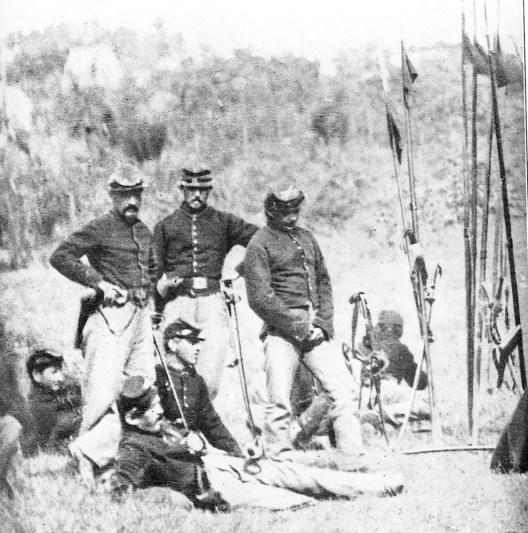

It was at the fourth generation (removed from me) that I discovered one veteran in particular that had really captured my attention. My 3-times great-grandfather was a veteran of the American Civil War (ACW). I took several notes of his vital information and continued searching. I found that two of his grandfathers and at least one great-grandfather were veterans of the Revolutionary War. With this information, I established a stopping point and began to focus on ferreting out as much data as I could find. I decided to hone in on the Civil War veteran and began exhausting all of the online resources.

After receiving two packets of information following a National Archives request (and several weeks of waiting) I began to piece together what my ancestor did during his time in service. Like thousands of young men across the Union, my great, great, great-grandfather, Jarius Heilig, volunteered (September, 1861) to serve alongside his (Reading, PA) neighbors and relatives, enlisting into the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (70th Pennsylvania Volunteers) – a unit formed by Colonel Richard Henry Rush (son of Richard Rush who was President Madison’s Attorney General and grandson of Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence), classmate and friend of General George McClellan.

One interesting fact about the 6th Penna is that their primary weapon. the lance (rather than the standard U.S. cavalry-issued carbine rifle), was suggested by McClellan, harkening to the once-feared European dragoons and cavalry units. The weapon is described as:

“The Austrian pattern was adopted. It was nine feet long, with an eleven inch, three edged blade; the staff was Norway fir, about one and a quarter inches in diameter, with ferrule and counterpoise at the heel, and a scarlet swallow-tailed pennon, the whole weighing nearly five pounds.”

Though injured (by a horse-kick, of all things) at the end of 1862, Heilig had seen his share of combat serving entirely with “F” company until his February 1863 discharge (due to disability), with action in the following battles and skirmishes:

-

Skirmish, Garlick’s Landing, Pamunkey River, VA (June 13, 1862)

-

Seven Days Battles, VA (June 25-July 1, 1862)

-

Battles, Gaines Mill, Cold Harbor, Chickahominy, VA (June 27, 1862)

-

Battle, Glendale, Frazier’s Farm, Charles City Crossroads, New Market Crossroads, Willis Church, VA (June 30, 1862)

-

Battle, Malvern Hill, Crew’s Farm, VA (July 1, 1862)

-

Skirmishes, Falls Church, VA (Sept. 2-4, 1862)

-

Skirmish, South Mountain, MD (Sept. 13, 1862)

-

Skirmish, Jefferson, MD (Sept. 13, 1862)

-

Action, Sharpsburg, Shepherdstown, and Blackford’s Ford (Boteler’s Ford) and Williamsport, MD (Sept. 19, 1862)

-

Actions, Bloomfield and Upperville, VA (Nov. 2-3, 1862)

Research resources are quite abundant for this unit (which I am still pouring through) and it has been the subject of a handful of books that were the product of painstakingly thorough historical investigation.

What does this have to do with militaria collecting, you might be asking? Part of my quest in producing a historical narrative of my familial military service is to provide visual and tangible references. To illustrate history, words are only part of the equation in connecting the audience to the story. To see, smell and touch a piece of history provides an invaluable accompaniment to the narrative.

I have given considerable thought to my approach in gathering items to assemble a group of artifacts as a “re-creation” of things my great-grandfather might have kept over the years. Visual appeal, authenticity, believability and cost were all factors guiding me as I purchase various pieces for the collection. My goal with the group is to arrange it into an aesthetically pleasing display that I can then hang on my home office wall (along with the displays I have already created).

Collecting artifacts from the American Civil War is not a task that can easily be easily accomplished on a shoestring budget (such as my own). Seemingly everything is expensive from weapons (rifles, pistols and edged weapons) down to ordinary uniform buttons seen on literally millions of soldiers’ uniforms. The high prices and the popularity of the Civil War’s historical popularity (which is maintained by pop-culture with films like Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln) can have detrimental effects on the market as unscrupulous counterfeiters work tirelessly to cash in.

Adding to my challenge is the fact that there were far fewer cavalry soldiers who served during the war. Even more challenging is that my ancestor served with a state volunteer cavalry regiment, many of which had extremely unusual uniform appointments and accouterments requiring even more research and discernment as to what my 3x-great grandfather would have been outfitted with.

These factors (combined with my own lack of experience) limited my focus to keep the pursuit as simplistic and affordable as possible while focusing on the more common ACW pieces for the display.

Since I embarked on this mission, I have acquired several pieces – a mixture of genuine and reproduction (recommended by a collector colleague) – that will display nicely together. From hat devices to corporal’s stripes (repro) to veteran’s group medals (GAR – Grand Army of the Republic – an ACW vets’ organization my ancestor was a lifelong member of). In addition, I’ve collected some small arms projectiles (from weapons Heilig would have carried) excavated from battlefields where my great-grandfather fought.

I am constantly on the lookout for pieces that would display well or that might be interesting additions to my militaria collection that could be directly tied to my ancestor’s unit. When a cavalry guidon flag (directly connected to the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry) was listed at online auction, my heart raced as I eagerly poured over the photos of the tattered and worn swallow-tailed cloth.

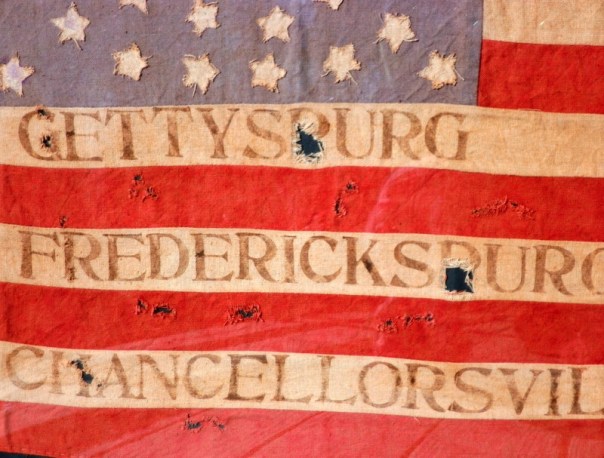

As was the custom of the Civil War, the major battles and engagements in which the unit participated were printed directly onto the stripes on the fly of the flag (source: eBay image).

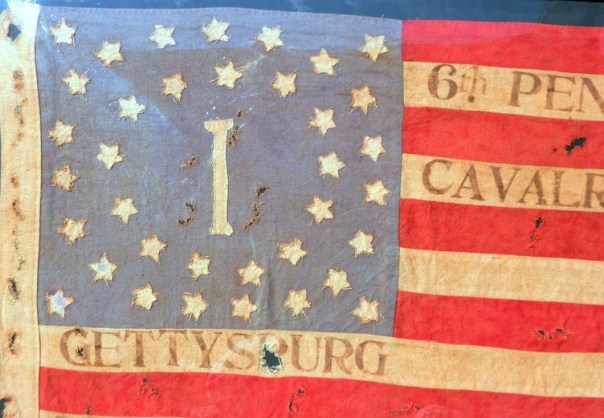

Lost in the detailed images of the flag, I was amazed to see the faded relic nicely preserved in a frame behind glass. Bearing marks of the unit and the major battles printed directly on the red and white stripes, this flag appeared to be a true relic of the past. The the “I” designator in the blue canton (encircled by the white stars of the states) indicated that this was the guidon from I company (my great-grandfather served in company “F”). Everything about this flag excited me…until I read the description. The flag was a recreation of the original (which is permanently preserved and displayed at the Pennsylvania state house), right down to the synthesized aging (at least the seller was being honest about the piece).

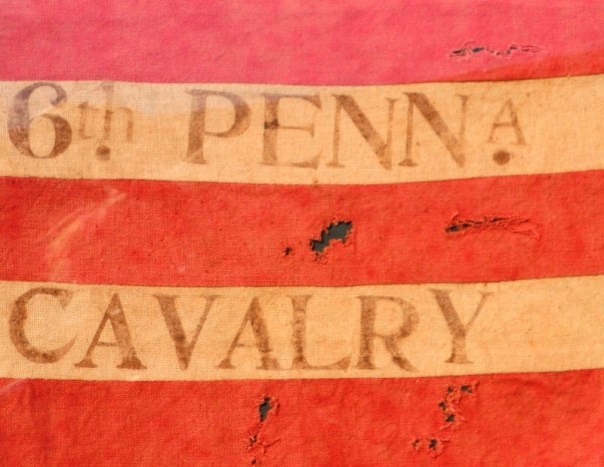

Aside from the tell-tale swallow-tail design of the flag, the printed unit name indicates that this flag was from a cavalry regiment – specifically, the 6th Pennsylvania (source: eBay image).

The letter “I” in the center of the blue canton represents the associated company within the 6th Pennsylvania that used this guidon (source: eBay image).

Had the price of the auction been realistic, (the starting bid was $1,000), I would have been interested in pursuing it as a realistic accompaniment to the display I am assembling.

Recreation or Reorder: Are These Patches Reproductions?

Collecting patches is a significant and one of the oldest segments of the militaria hobby. So much so that they established an organization (in the late 1930s), the American Society of Military Insignia Collectors (ASMIC), to better facilitate the exchange of the patches and metal insignia from American military uniforms.

Prior to World War I, U.S. armed forces were only adorned with rank insignia (chevron patches on sleeves for enlisted, collar devices and epaulettes for officers). During the Great War, units began affixing cloth insignia to their shoulders to provide visual indication of the unit to which they were assigned. This practice quickly spread as the war began winding down late in 1918 and became widely adopted, not only in the U.S. Army, but also the Marine Corps and some Naval personnel.

See:

In World War II, the expansion of incorporating insignia to identify aircraft squadrons and other smaller units (versus Army regiments or divisions). These “logos” were caricatures that embodied general traits of the unit, their mission or even their founding leadership. Aircraft squadron insignia from WWII, naval squadrons in particular, are some of the rarest and most sought-after patches by collectors.

This flannel VF-111 Sundowners patch resembles that of an original WWII version (of VF-11), though it seems to be a modern representation.

See:

By the 1980s, unit insignia had become quite commonplace across all units within the US armed forces branches. In the Navy, as each new ship was placed into service, accompanying them was an officially designed and approved unit crest that bore visual representations of the ship’s name. Subsequently, the ships’ stores (where the crew members buy personal supplies, snacks and ship-branded merchandise) would offer, for sale, fully-embroidered patches of the crest.

When a ship is decommissioned (put out of service), the logos and subsequent merchandise cease to be available (other than in secondary markets). Nostalgic veterans and collectors not wanting to wait for one or two of the ship’s patches to become available in online auctions are left with scant few options. This was a situation that I recently had the joy of resolving for my former shipmates who were more than two decades removed from serving aboard our ship, the cruiser USS Vincennes.

This terrible patch lacks the detail of the crest. Everything is wrong with this example from the coloring to the design elements and lettering. It is just awful.

In the past few years, an Asian-made (poor) representation of the patch was being sold infrequently in online auctions. This patch a terrible facsimile of the original as it lacked all the detail of the ship’s crest. The seller had that audacity to charge more than $10 (plus shipping) for this poor quality example. A few of my shipmates, desperate to fill a void in their ship memorabilia collection, ponied up the funds and buying the pathetic patches.

Recognizing an opportunity to remedy this issue, I went through a lengthy process of locating the original manufacturer and soliciting bids based upon the original patch design. Today, I was happy to report to my shipmates that the patches would be in their hands within a few days. The shipment of authentic ship crest insignia had arrived.

Some of you might be asking, “Is this really militaria if you’re just having it made?” I can attest that though these are newly manufactured, the patches are no different from those made (by the same manufacturer, by the way) two and a half decades ago.

Militaria Collecting: It Isn’t Just Fatigues and Helmets

Why Collect Militaria?

I try to resist talking to people outside my sphere of militaria collecting acquaintances and friends for the simple reason that I choose to avoid the typical unrehearsed (body language) responses when they learn this particular interest of mine. You might have experienced it – the glazed, vacant stare – uninterested people seem to look way past you as you cautiously respond to someone seeking to learn something about you.

Many non-collectors envision scenes from military surplus stores when they hear militaria collectors speak about their interests and collections. (image source: Freedommilitarysurplus.com).

The perception is that militaria collectors are interested in a bunch of junk that can be found for pennies-on-the-dollar at a mildew-laden military surplus store. They assume that we are gobsmacked by olive-drab army fatigues, rusty canteens and other military cast-off items. You should see the eyes roll when I attempt to describe what truly inspires my collecting.

Militaria collecting represents an extensive and broad range of categories. For certain, there are elements such as uniforms, edged weapons, head-wear and medals/decorations at the hobby’s core. But there is incredible variety in this “genre.” Though my own collection pays homage to my veteran ancestors and relatives, I have dabbled in a few of these non-standard areas in militaria collecting. One in particular is the product of combining two passions sports (specifically baseball) and military history. I wouldn’t consider myself a hard core collector in this area, but I have been fortunate enough to land some great pieces that align these two interests. Other than my other focus area (naval history) which I have covered extensively, military sports, namely baseball, has been the subject of many postings in the past several years in writing about this passion:

Baseball Uniforms

- Stars, Stripes and Diamonds: Photographs of America’s Pastime in Uniform

- The Corps on the Diamond: US Marines Baseball Uniforms

Ephemera

Autographs

Military Football

Collecting militaria can pose some financial challenges when faced with stiff competition for rare or exceptional items. This is something I routinely face as with my special interest in items pertaining to a specific U.S. Navy warship (actually four of them) that was named for a city in Indiana. When items associated with this ship turn up in online auction listings, the competition can get rather fierce, pushing the bidding price out of my range of affordability. There are times when one of the pieces does manage to slip past my competitors allowing my maximum bid to be sufficient in securing the prize. These are rare occurrences that when they do happen, I am elated to the point of becoming borderline-addicted to collecting.

While this particular uniform group (of a WWII radioman 2/c submariner) is on display at a museum, I know of several collectors who have their collections displayed in similar, well-executed arrangements.

The point of militaria collecting is that it provides for a hands-on connection with history that transcends what is talked or written about in print. It provides those who are interested with a method to comprehend historic events or people while transforming what is read in books or portrayed on screen into (nearly) living history.

In future posts you will, no doubt, observe trends that belie my interests and what I tend to focus my collecting on. However, I will also attempt to provide you with informative posts in order to share the knowledge I’ve gained from a vast network of collectors, historians, museum curators and several other knowledgeable people in order to assist you in making wise decisions with your acquisitions.