Militaria Rewards – Researching the Veteran

One aspect of collecting militaria is the discovery that the item you’ve just purchased has a veteran’s name associated with it. Quite often, U.S. military-related pieces are marked with a soldier, airman, marine or sailor’s last name, initials and/or service number. In some cases, while not possessing a name, uniform items can have a laundry number inscribed in them. This information can provide the collector with a means of researching the veteran to determine where and when he or she served, as well as awards and decorations earned.

In one of my earlier posts, I described how collectors should buy the item as opposed to buying the story. With these named items, we have the potential to provide the actual story to accompany the item in order to explain where the particular item may have been used or worn. At the very least, the piece’s original ownership can be established.

For many collectors, the potential for owning an item that is named to a veteran who has significantly contributed to historically important military events or battles is akin to striking gold. To discover that the uniform you just purchased was worn by a Valor Award recipient (Medal of Honor, Navy Cross, Distinguished Service Cross, etc.) is exciting and very rewarding as they are relatively rare. Proving with iron-clad documentation that the name stenciled into your uniform is THE person who you believe them to be can be a challenge.

Researching a U.S. veteran can be difficult and time consuming, and you have to be committed to the end-goal if you are seeking definitive results. There can be considerable costs associated with research as well. These factors will lead many collectors to be content with an un-researched piece remaining in their collection.

Before you can begin the research of the veteran’s name, you need to determine several basics about it.

- What period is this piece from? Look at the construction. Pay attention to the details.

- How was it made?

- For WWII and earlier uniform pieces, determine what materials it was constructed from. Does the fabric or stitching glow during a black-light test?

If you can determine the veracity of the item for the suspected time frame, you can move on to researching the veteran’s name with a measure of confidence.

There are a few decent online research resources to conduct searches for your veteran’s name. Some sites, such as the National Archives (NARA), are free to use. However, they aren’t complete and just because the veteran’s name doesn’t appear in the results, it doesn’t mean that you’ve hit a dead end. Below are a few of the resources I use.

Individual Veterans Research

- National Archives Access to Archival Databases (AAD): http://aad.archives.gov

- Ancestry: http://www.ancestry.com (paid subscription only)

- Fold3: http://www.fold3.com (paid subscription only)

Branch and Unit History

- Air Force Historical Research Agency: http://www.afhra.af.mil

- Naval Historical and Heritage Command: http://www.history.navy.mil

- US Marine Corps History Division: http://www.tecom.usmc.mil/HD/

- US Army Center of Military History: http://www.history.army.mil

- Army Historical Foundation: http://www.armyhistory.org

- Defense Military Imagery: http://www.dodmedia.osd.mil

When it comes to researching an individual veteran, Ancestry.com is invaluable as they seem to have the most comprehensive amount of available data online. In order to obtain access to that data, you will need to pay for a subscription. The military-specific results found in Ancestry will provide you with some basic information such as draft cards, muster rolls (which contain service numbers) and pension records. These details can give you solid direction to take for submitting requests via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) for more detailed information from the National Archives such as:

- Separation Documents

- Service Records

- Medical Records

If a veteran’s name is more unique, researching can become easier. Surnames such as Smith, Jones or Johnson can be extremely difficult to pinpoint with research. Having a service number to associate with the veteran can truly help solidify your results, although there have been instances where the service number cannot be located within NARA. This could be the result of the 1973 fire where 16-18 million records were destroyed. Slowly, the records are being restored and there is a chance that with time, your veteran’s records may be available.

Two of my uniforms (that I have selected to demo in this post) are named. The first is a set of World War II dress blues for an Aviation Radioman 3/c that are tailor made (the sailor had them made especially for himself) with his name and initials embroidered into both the jumper top and the pants. The blues feature a side zipper and a very slim cut to make the uniform more form-fitting. Also in this tailored set are secret pockets to conceal money or identification from pickpockets or con artists. This jumper also features the aircraft gunner distinguishing mark and ruptured duck discharge patches (the ribbons and aircrew insignia pin were added by me for display purposes).

First up, Aviation Radioman Third Class (aerial gunner, aircrew), P.D.S. Leahy:

- The overall view: Leahy was a aerial gunner (the distinguishing mark on the right arm) and his rate was Aviation Radioman.

- Aviation Radioman 3/c P. Leahy uniform.

- This view clearly shows the custom-fitment of the zipper (to allow for a tighter fit while still affording the sailor to pull this on and off with relative ease. Also note the post-war ruptured duck on the right breast and the aircrew pin.

- The ribbons for this man show that he was a Pacific Theater sailor and spent time inside of an aircraft (as noted by his aircrew pin).

- Custom or tailored uniforms are often adorned with flair such as this anchor-inspired, colorful embroidery.

- Aviation Radioman 3/c P.D.S. Leahy is embroidered into this custom tailored service dress blue uniform jumper.

A search on Ancestry produced a single record that more than likely is the veteran that owned this uniform – the name Philip D. S. Leahy is very unique. Unfortunately, there isn’t any more information which means that I will have to take this information and turn to other resources to find out more about this sailor.

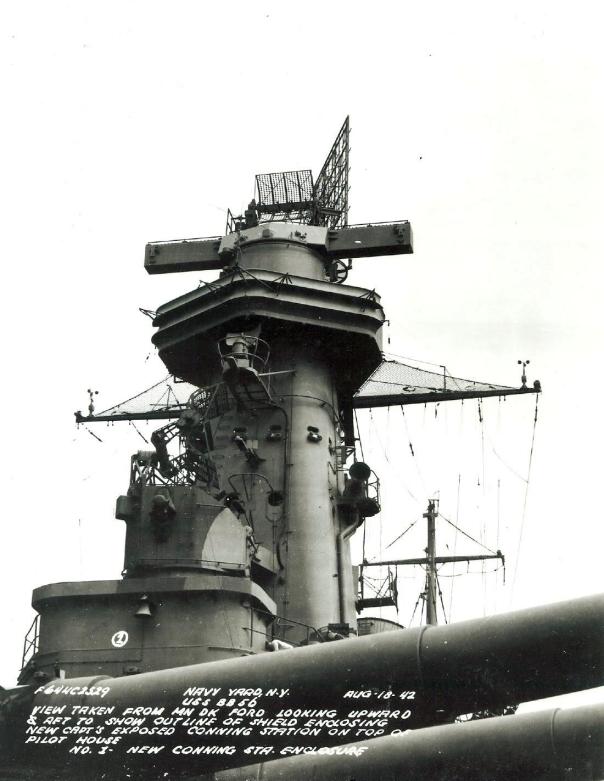

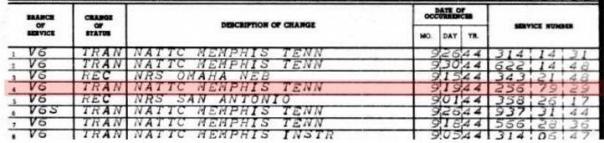

Ancestry Search – This muster sheet clearly shows Philip D S Leahy as a seaman second class being transferred from the Naval Training Center, Jacksonville, FL to the Naval Air Technical Training Command in Memphis, TN.

Ancestry Search – This muster sheet clearly shows Philip D S Leahy as a seaman second class being transferred from the Naval Training Center, Jacksonville, FL to the Naval Air Technical Training Command in Memphis, TN.

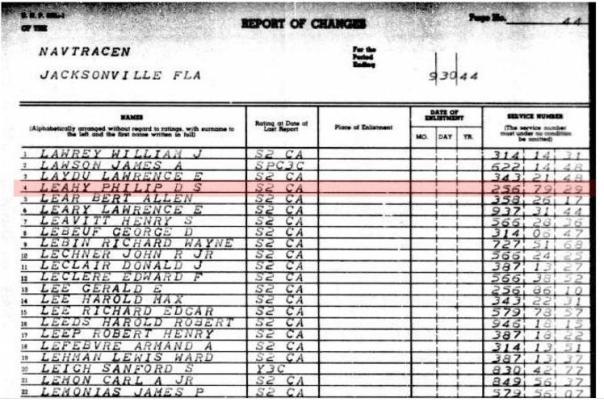

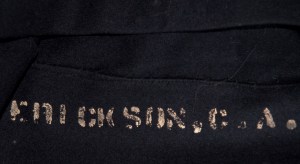

The next named WWII navy uniform, a Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class dress blue jumper, is named to a C. A. Erickson.

- My WWI-era Ship’s Cook, second class is stenciled with the name, “C. A. Erickson” inside and above the hem.

- Ship’s Cook/Baker, C. A. Erickson is clearly stenciled inside the dress blue uniform jumper.

- Three stripes on the cuff denote that this sailor advanced to seaman (and then onto petty officer second class).

- C. A. Erickson’s rating badge is trimmed like most of the sailors of the WWI era.

- The proper way to store a navy dress blue uniform is inside out and creased down the center. This gives the uniform a unique appearance and the flap lays with an intentional appearance with three equally distributed creases.

- Showing the underside of C. Erickson’s jumper flap.

After an exhaustive search in the navy muster rolls, I have come up empty handed. While there are several names that match or come close, none align with this uniform.

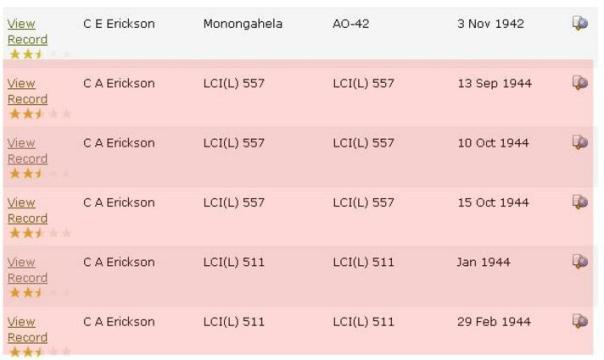

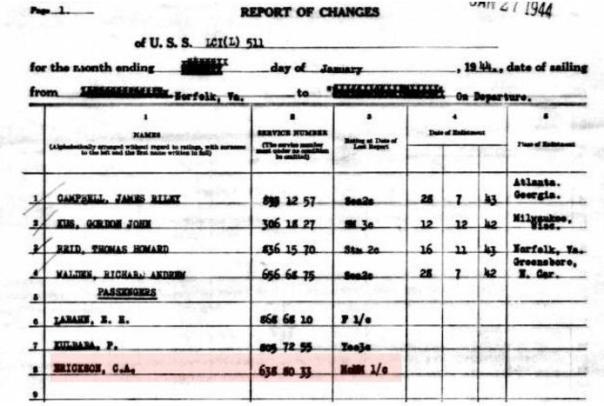

Searching through Ancestry I found the C.A. Erickson results and there were several records to choose from.

Again I will have to turn to other resources to see if I can find the name. I have less to go on than the first example.

In a future post, I will tackle the next level of researching veterans and submitting FOIA requests.

The Merits of Heart Collecting

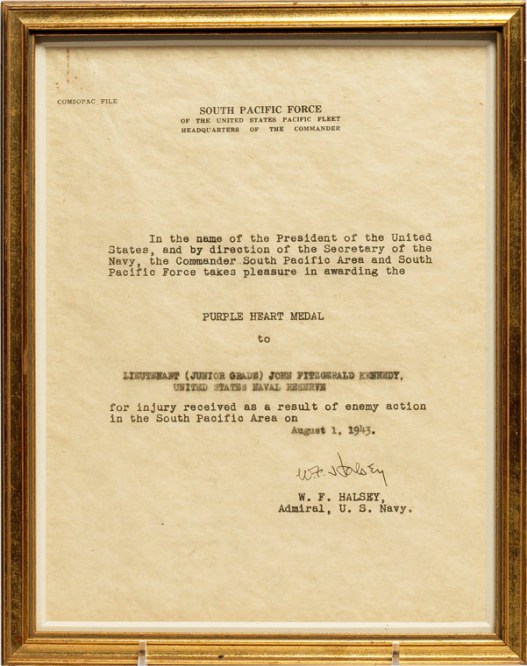

The Purple Heart Medal has been awarded since 1932 to veterans who were wounded or killed in action in WWI through the current conflicts. This image shows both the front and the reverse of the PHM which includes the inscription-relief, “For Military Merit” and the space beneath where it is traditionally engraved with the recipient’s name and rank.

One of the most sacred military medals created for service personnel of the United States military is one that can only be “earned” by receiving a wound inflicted by an enemy in combat. Since February 22, 1932 (the 200th anniversary of General George Washington’s birth), the Purple Heart Medal (PHM) has been awarded to members of the U.S. armed forces who sustained combat-related wounds (or were killed in action) on the field of battle, from World War I (retroactively by the veteran’s request) through the present conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Beautifully sculpted in a gold tear-drop shape with Washington’s bust profile superimposed in a heart-shaped field of purple, the Purple Heart is a highly sought after item for militaria collectors. The medal was a revival of a design of an award that was presented by General Washington in 1782 that was presented to three soldiers during the Revolutionary War as a Badge of Military Merit.

Collecting the medal can be offensive to laymen who can be repulsed by the idea of a collector who treasures something that is specific to the suffering or death of a service member. For me, I have somewhat mixed feelings about the concept.

Prior to departing for my first combat deployment, my father, a Viet Nam veteran, advised me to avoid seeking a Purple Heart as if he was directing one of his young charges back in 1969. Of course, I survived my deployment physically unscathed returning home without the bust of George on my chest.

Affectionately known as a “coffin case,” this presentation box is inscribed with the name of the medal in gold leaf.

When I encounter veterans who have been awarded the medal, I have a great deal of respect for them. Not because they were wounded, but that they offered themselves up voluntarily, knowing what the personal cost could be. For those who survive their wounds, the road to recovery can last months, years or a lifetime. World War II war correspondent Keith Wheeler described in horrific detail what that road looks like in his 1945 book, We Are The Wounded, telling of his own experience after being wounded (shot) on Iwo Jima. As a civilian, Wheeler was ineligible to receive the award, but he certainly earned it as what he endured paralleled that of the combat veterans who were medically treated alongside him.

For collectors, at least the ones I know, the medal is sacred. To them, the medal is a representation of the sacrifice made by the recipient denoting significance in personal military history. Over the years as family members and descendants (of those veterans) who have lost personal connection to that history, allow the military items to be sold. Many collectors have revealed that they’ve saved items from garbage cans and dumpsters as they were callously discarded.

This is a World War II Purple Heart Medal set complete with the ribbon and lapel device in the correct presentation case.

Most Purple Heart medals issued through the Viet Nam War are engraved with the recipient’s name affording collectors with the ability to research them and reconstruct the personal history. Several collectors create veteran dossiers for each of the PHMs in their collection displaying them alongside their collection at public Memorial and Veterans Day events, describing the price that was paid by each individual.

I have two PHMs in my collection. One of them is part of the medals that were awarded to my uncle who was wounded in World War I and again in World War II. He also served in the Korean War finishing his service in 1954. The other example is one that I acquired that is an un-engraved (and numbered on the edge) WWII-issue, complete set (including the ribbon and lapel devices) in the presentation cases.

Purple Heart Collections

Remembering (and Collecting) the USS Maine!

In the decades following the American Civil War, the United states was busy dealing with the reconstruction of the South, expansion into the Western states and territories, adding new stars to the blue canton of the national ensign (i.e. the addition of states to the Union), the influx of the destitute of Europe seeking to benefit from the Land of Opportunity and all the trefoils of a growing nation. Few Americans set their eyes upon the instability of governments beyond the borders and shores as the nation surpassed her first century of existence. Life, though fraught with the many diverse challenges of the time, was good.

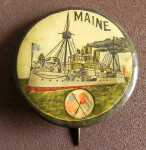

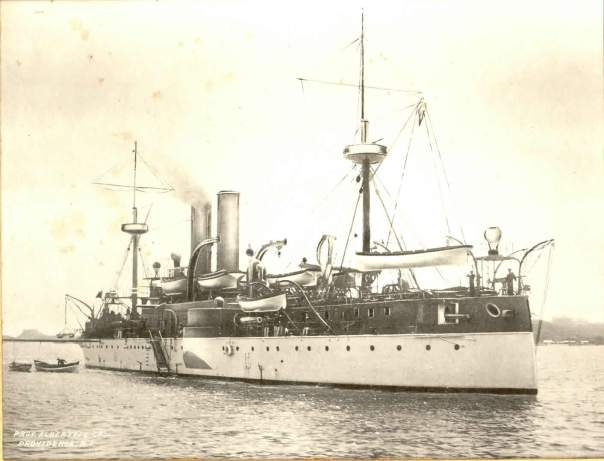

USS Maine ACR-1 – Havana Harbor, 1898

In the latter half of nineteenth century, the American navy commenced a dramatic technological transformation from wooden-hulled sailing sloops and frigates, followed by ironclads and paddle-wheels, to steel coal-fired steam warships. Naval gunnery was advancing and the U.S. leadership was following the advances being made by the British navy that had necessitated a radical departure from the ship design convention (of the time) in order to take full advantage of the new capabilities. The U.S. Navy, had been fully committed to the designs of the ironclad Monitor and many of the European navies adopted similar designs following the American’s success with them during the Civil War. With technology advancing at such a rapid pace and the need for a global naval reach, the Monitor was rendered obsolete, in favor of larger, more powerful ships with greater sailing range which would come to be known as pre-Dreadnoughts.

In the 1880s, the U.S. Navy began planning and designing their first pre-Dreadnought armored cruisers. By 1886, the Navy funded the first two ships of the new design, the lead ship, USS Maine and her (closely-related) sister, the USS Texas. The Maine’s keel was laid down on October 17, 1888 at the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard and wouldn’t be completed for nearly seven years. She was commissioned and placed into service on September 17, 1895 and following sea trials and fitting out, was assigned to the North Atlantic Squadron for service.

As the 1890s were drawing to a close, a spark in the tinderbox of the Cuban independence movement began to be fanned by U.S. financial influence. American capitalism and politics had been involved in Cuba for the past few decades investing heavily in the sugar cane and tobacco industries, driving economic transformation of the Spanish-owned island and fueling unrest among the citizens. American popular sentiment, led by a pro-liberation agenda that was propagandized throughout the newspapers of the day, was growing in favor of intervening against the Spanish government. In January of 1898, a pro-Spanish riot erupted in Havana which prompted the American Consul-General to request assistance to protect U.S. citizens and business interests.

Sailing into Havana Harbor at the end of January, the USS Maine provided a menacing reminder of the United States’ commitment to protect her interests. In addition, her presence could have appeared to the Spanish loyalists as a threat to their sovereignty. Perhaps the revolutionaries saw the ship as an opportunity to draw the United States into a conflict with Spain that could result in the ouster of their oppressive overseers. Regardless of the stance of the two opposing sides, the Maine’s presences added to the already increasing tension.

Aboard ship, the crew was going about settling down for the night on February 15, 1898. Twenty minutes before taps and lights out, the shipboard routines were winding down. Liberty boats had returned to the ship and had been secured for the night. Suddenly and without warning, a massive explosion rocked the forward part of the ship as 5.1 tons of gunpowder ignited. In a matter of seconds, the Maine was sitting on the bottom of the harbor and more than 260 of her crew (of 355 officers and men) were dead.

Galax leaf wreaths decorate the coffins containing the dead of the Maine on December 28, 1899.

Following a formal investigation and inquiry into the cause of the explosion, the cause was determined to be the result of a mine (though no supporting evidence existed). The slogan of the day, “To hell with Spain! Remember the Maine” could be found in print and plastered across buttons and pins as the American public began to rally to the cause. Following the publication of the findings, a media blitz of inflaming editorials and exaggerated facts ultimately led to an April 21, 1898 formal declaration of war against Spain.

- America fights back. This button demonstrates the angry sentiments of the day with, “Remember the Maine – Gosh Darn Yer” (source: eBay image).

- More subdued, the message is still clear with regards to the Maine’s sinking. Note the crossed American and Cuban flags (source: eBay image).

- USS Maine cast iron coin bank (source: eBay image).

- Several versions of this candy dish are readily available in antique shops and online auction listings. I have found several colors – clear, two shades of green, and cobalt blue (source: eBay image).

After resounding victories in Manila Bay (in the Philippines) and San Jaun Hill (Puerto Rico), the Spanish pursued peace with the United States by the middle of July, 1898. The peace treaties were signed in Paris on August 12, 1898, relinquishing all rights and claims to the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

With the guns now silent and the U.S. reverting to their isolationist stance, the rallying cry of “Remember the Maine” began to fade from the forefront of the U.S. populace. This was not so with Navy leadership who were still seeking definitive facts surrounding her sinking. In 1910, Navy engineers began constructing a cofferdam surrounding the shallow-water wreck of the ship. After the harbor waters receded from the wreck, investigators poured over every inch of the hulk. With no conclusive evidence uncovered and the bodies of the crewmen were removed for burial in the U.S. (at Arlington National Cemetery), the ship was refloated, towed out to sea and scuttled.

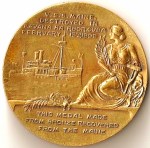

- This outstanding example of a USS Maine medallion commemorates the ship and the Pittsburgh, PA memorial that was dedicated in 1914. The inscription on the obverse reads, “U.S.S. Maine, Destroyed in Havana Harbor, Cuba, February 15th, 1898.This medal made from bronze recovered from the Maine.”

- The inscription on the medallion’s reverse reads, “Issued by the general committee of the fifteenth annual reunion of the army of the Philippines, Cuba and Porto Rico, in memory of our deceased comrades and the dedication of the Maine Memorial. Pittsburgh, PA | September 16th, 1914.”

- This rare pin calls for Americans to avenge the sinking of the Maine (source: eBay image).

- Remember the Maine Medallion obverse showing Admiral Dewey (source: eBay image).

- This tally (from the BB-10) recently recently sold for under $200 (source: eBay image).

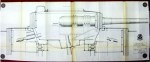

- USS Maine Turret Technical Drawing USS Maine turret technical drawing (source: eBay image).

Bell of the USS Maine, broken in half by the 1898 explosion, attached to the door of the memorial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Several pieces of the ship were removed at the time of the 1910-1912 investigation including munitions, guns, pieces of her superstructure and mast and other items that would serve as central components of memorials that were being constructed around the country. Commemorative medallions were cast from metal retrieved from her screws as Americans renewed their commitment to remember the Maine.

Four years following the devastating loss of the cruiser, the U.S. Navy commissioned the USS Maine (BB-10), the lead ship of three-ship class of battleships which also included the USS Missouri (BB-11) and USS Ohio (BB-12). The second USS Maine would proudly carry the name and legacy in Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet and through World War I. Her 18-year career ended with her May, 1920 decommissioning. The Maine name wouldn’t sail again until 1994 when the Navy launched the 16th Ohio-class Trident submarine, USS Maine (SSBN-741) which is currently homeported in Bangor, Washington.

More than 110 years later, the stricken USS Maine resonates with a minute segment of collectors. While very few items or artifacts originating from the ship surface within the marketplace, memorial pieces are readily available.

Inscription on the Havana USS Maine monument:

“El Pueblo De La Isla De Cuba Es Y De Derecho Debe Ser Libre E Independiente.” Resolucion con junta del Congreso de los Estados Unidos de Norteamerica De 19 de April De 1898.

“The people of the island of Cuba are and of right ought to be free and independent.” Congressional joint resolution with the United States of America from April 19, 1898.