Category Archives: Uniforms

The Militaria Collector’s Search for the White Whale

The hunt. The search. The quest for the prize. Seeking and finding the “Holy Grail.” We collectors tend to describe the pursuit of those elusive pieces that would fill a glaring void in our collection with some rather lofty terms or phrases.

We wear our collection objectives on our sleeves while pouring through every online auction listing, or burning through countless gallons of gasoline while making the rounds from one garage or yard sale to the next. Antiques store owners (whom we think are our friends) have our lists of objectives to be on the lookout for.

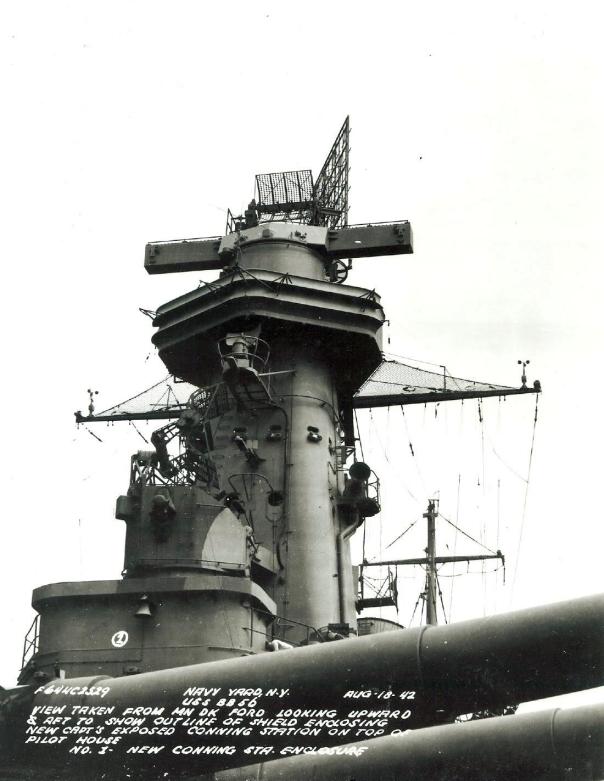

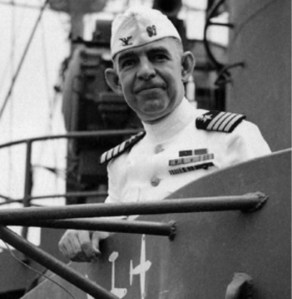

A close-up of the USS Astoria’s first commanding officer, Captain George C. Dyer, wearing his choker whites and the rare white garrison cover (source: Brent Jones Collection).

Militaria collectors (any collector, for that matter) thrive on the hunt and feed off the adrenaline rush that comes from achieving each victory as they locate and secure the piece that has seemingly evaded every search effort. Hearing that they’ve missed an opportunity by seconds due to some other collector beating them out only fuels their passion. Losing an auction because they tried to play conservatively with their bidding propels them through the twists, turns, hills and valleys of the emotional roller coaster.

Searching for militaria can be an exhausting endeavor. For the last two years, I’ve been searching for a piece and while I can’t say that I’ve been through these scenarios, I did manage to feel an amount of elation when I achieved success with my objective.

This shot shows Captain George C. Dyer departing the Astoria wearing his dress white uniform and the white garrison cover (source: Brent Jones Collection).

I’m not wanting to repeat myself (which I do quite often, considering all of my previous posts), but let me state that I do not consider myself any manner of expert on military history or militaria. I assert that I have a broad-based knowledge on a narrow scope of U.S. military history (20th century) with a primary focus on the U.S. Navy. So when I discovered an item that I had previously never knew existed, I was quite curious and subsequently needed to obtain it.

An acquaintance (who had contributed photos for my first book that I published in 2009) has a website that is the public face of his extensive and invaluable research on the USS Astoria naval warships. On this site, I noticed some new images that he had recently obtained and published showing the first commanding officer, Captain George C. Dyer, of the USS Astoria CL-90 turning over command of the ship and departing amidst his change of command ceremony.

Pictured here with an early WWII chief radioman’s eight-button, dress white uniform jacket, the (yellowing and aged) white garrison cover is a bit more distinguishable from a khaki variant.

For the ceremony, the ship’s crew is turned out in their summer white dress uniforms. All appeared to be normal until I spied the unusual uniform item – the commanding officer was wearing a garrison cover (hats in the Navy or Marine Corps are known as covers). Affectionately known as a (excuse the crass term) “piss cutter,” I knew that the garrison was available for use with the (aviator) green, khaki, (the short-lived) gray and the blue uniforms, but I had never seen a photo of this white variety. Garrison covers are not particularly stylish, but due to their lightweight and soft construction, they are considerably more comfortable than the traditional combination cover (visor caps) alternatives.

A Garrison Comparison: at the top is the white garrison (compared with a WWII khaki) demonstrating that, though it is yellowed, it is the rare white cap.

Plentiful and very readily available, the khaki versions are quite frequently listed or for sale at antiques stores and garage sales. The green, gray and blue garrisons are a little bit more rare yet turn up with some regularity. The white garrison is the great, white whale. Considering that it was not well-liked in the fleet during the war (when it was issued), it is now extremely rare for collectors seeking to possess all of the uniform options. The white garrison is truly the white whale among World War II navy uniform items.

Seeing this hat in the photos fueled my quest to obtain one for my collection. The very first one I had ever seen listed anywhere became available last week at auction. I placed my bid at the very last second and was awarded with the holy grail. Yesterday, the package arrived and was both elated and saddened as my quest was fulfilled.

No longer needing to hunt for this cover, I feel as though I have lost my way… a ship underway without steerage. What am I saying? I have plenty of collecting goals un-achieved!

Militaria Rewards – Researching the Veteran

One aspect of collecting militaria is the discovery that the item you’ve just purchased has a veteran’s name associated with it. Quite often, U.S. military-related pieces are marked with a soldier, airman, marine or sailor’s last name, initials and/or service number. In some cases, while not possessing a name, uniform items can have a laundry number inscribed in them. This information can provide the collector with a means of researching the veteran to determine where and when he or she served, as well as awards and decorations earned.

In one of my earlier posts, I described how collectors should buy the item as opposed to buying the story. With these named items, we have the potential to provide the actual story to accompany the item in order to explain where the particular item may have been used or worn. At the very least, the piece’s original ownership can be established.

For many collectors, the potential for owning an item that is named to a veteran who has significantly contributed to historically important military events or battles is akin to striking gold. To discover that the uniform you just purchased was worn by a Valor Award recipient (Medal of Honor, Navy Cross, Distinguished Service Cross, etc.) is exciting and very rewarding as they are relatively rare. Proving with iron-clad documentation that the name stenciled into your uniform is THE person who you believe them to be can be a challenge.

Researching a U.S. veteran can be difficult and time consuming, and you have to be committed to the end-goal if you are seeking definitive results. There can be considerable costs associated with research as well. These factors will lead many collectors to be content with an un-researched piece remaining in their collection.

Before you can begin the research of the veteran’s name, you need to determine several basics about it.

- What period is this piece from? Look at the construction. Pay attention to the details.

- How was it made?

- For WWII and earlier uniform pieces, determine what materials it was constructed from. Does the fabric or stitching glow during a black-light test?

If you can determine the veracity of the item for the suspected time frame, you can move on to researching the veteran’s name with a measure of confidence.

There are a few decent online research resources to conduct searches for your veteran’s name. Some sites, such as the National Archives (NARA), are free to use. However, they aren’t complete and just because the veteran’s name doesn’t appear in the results, it doesn’t mean that you’ve hit a dead end. Below are a few of the resources I use.

Individual Veterans Research

- National Archives Access to Archival Databases (AAD): http://aad.archives.gov

- Ancestry: http://www.ancestry.com (paid subscription only)

- Fold3: http://www.fold3.com (paid subscription only)

Branch and Unit History

- Air Force Historical Research Agency: http://www.afhra.af.mil

- Naval Historical and Heritage Command: http://www.history.navy.mil

- US Marine Corps History Division: http://www.tecom.usmc.mil/HD/

- US Army Center of Military History: http://www.history.army.mil

- Army Historical Foundation: http://www.armyhistory.org

- Defense Military Imagery: http://www.dodmedia.osd.mil

When it comes to researching an individual veteran, Ancestry.com is invaluable as they seem to have the most comprehensive amount of available data online. In order to obtain access to that data, you will need to pay for a subscription. The military-specific results found in Ancestry will provide you with some basic information such as draft cards, muster rolls (which contain service numbers) and pension records. These details can give you solid direction to take for submitting requests via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) for more detailed information from the National Archives such as:

- Separation Documents

- Service Records

- Medical Records

If a veteran’s name is more unique, researching can become easier. Surnames such as Smith, Jones or Johnson can be extremely difficult to pinpoint with research. Having a service number to associate with the veteran can truly help solidify your results, although there have been instances where the service number cannot be located within NARA. This could be the result of the 1973 fire where 16-18 million records were destroyed. Slowly, the records are being restored and there is a chance that with time, your veteran’s records may be available.

Two of my uniforms (that I have selected to demo in this post) are named. The first is a set of World War II dress blues for an Aviation Radioman 3/c that are tailor made (the sailor had them made especially for himself) with his name and initials embroidered into both the jumper top and the pants. The blues feature a side zipper and a very slim cut to make the uniform more form-fitting. Also in this tailored set are secret pockets to conceal money or identification from pickpockets or con artists. This jumper also features the aircraft gunner distinguishing mark and ruptured duck discharge patches (the ribbons and aircrew insignia pin were added by me for display purposes).

First up, Aviation Radioman Third Class (aerial gunner, aircrew), P.D.S. Leahy:

- The overall view: Leahy was a aerial gunner (the distinguishing mark on the right arm) and his rate was Aviation Radioman.

- Aviation Radioman 3/c P. Leahy uniform.

- This view clearly shows the custom-fitment of the zipper (to allow for a tighter fit while still affording the sailor to pull this on and off with relative ease. Also note the post-war ruptured duck on the right breast and the aircrew pin.

- The ribbons for this man show that he was a Pacific Theater sailor and spent time inside of an aircraft (as noted by his aircrew pin).

- Custom or tailored uniforms are often adorned with flair such as this anchor-inspired, colorful embroidery.

- Aviation Radioman 3/c P.D.S. Leahy is embroidered into this custom tailored service dress blue uniform jumper.

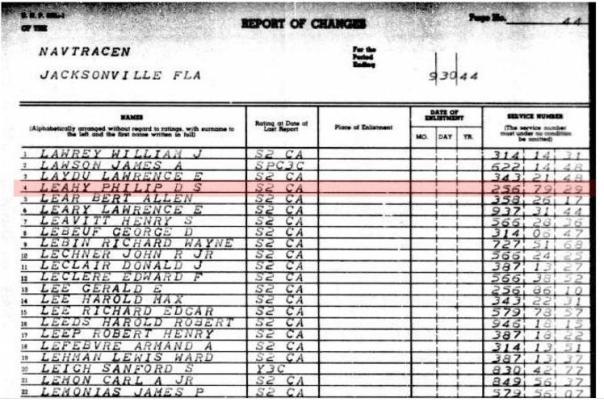

A search on Ancestry produced a single record that more than likely is the veteran that owned this uniform – the name Philip D. S. Leahy is very unique. Unfortunately, there isn’t any more information which means that I will have to take this information and turn to other resources to find out more about this sailor.

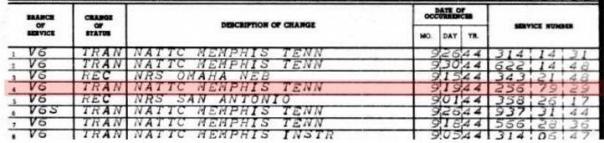

Ancestry Search – This muster sheet clearly shows Philip D S Leahy as a seaman second class being transferred from the Naval Training Center, Jacksonville, FL to the Naval Air Technical Training Command in Memphis, TN.

Ancestry Search – This muster sheet clearly shows Philip D S Leahy as a seaman second class being transferred from the Naval Training Center, Jacksonville, FL to the Naval Air Technical Training Command in Memphis, TN.

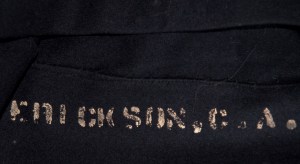

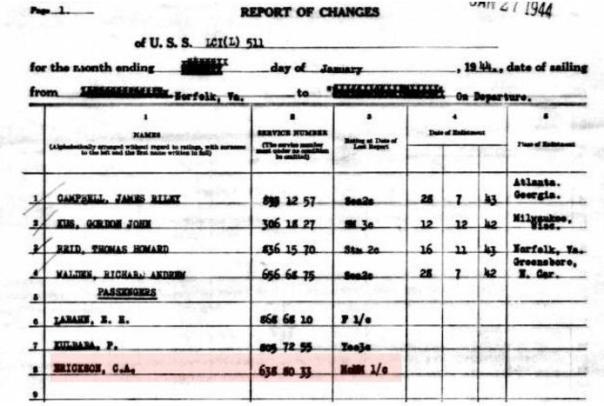

The next named WWII navy uniform, a Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class dress blue jumper, is named to a C. A. Erickson.

- My WWI-era Ship’s Cook, second class is stenciled with the name, “C. A. Erickson” inside and above the hem.

- Ship’s Cook/Baker, C. A. Erickson is clearly stenciled inside the dress blue uniform jumper.

- Three stripes on the cuff denote that this sailor advanced to seaman (and then onto petty officer second class).

- C. A. Erickson’s rating badge is trimmed like most of the sailors of the WWI era.

- The proper way to store a navy dress blue uniform is inside out and creased down the center. This gives the uniform a unique appearance and the flap lays with an intentional appearance with three equally distributed creases.

- Showing the underside of C. Erickson’s jumper flap.

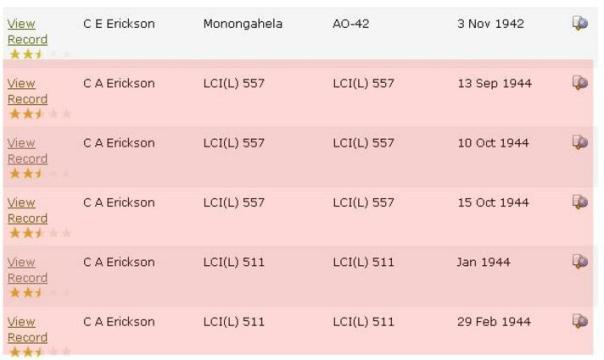

After an exhaustive search in the navy muster rolls, I have come up empty handed. While there are several names that match or come close, none align with this uniform.

Searching through Ancestry I found the C.A. Erickson results and there were several records to choose from.

Again I will have to turn to other resources to see if I can find the name. I have less to go on than the first example.

In a future post, I will tackle the next level of researching veterans and submitting FOIA requests.