Author Archives: VetCollector

Yardlong Photography and the Military: Family Military History Discovery in Less than a Yard

Because I am known within my family and circle of friends as the military-history person, I am on the receiving end of artifacts from those who know about my interests. From the moment that I was gifted with my maternal grandfather’s WWII navy uniforms and decorations (which can be seen in this post) and my grand uncle’s Third Reich war souvenirs, my appreciation for military history was ignited.

Over the years, I have either received or been approached to determine my interest in becoming the steward of historical family military items which have included, uniforms, medals and decorations, weapons (along with artillery rounds and small arms ammunition), flags, documents and other historical pieces. Some of the most special items that I have inherited have been photography (albums and individual photos). With the last box of items that were part of two family estates (my paternal grandparents and a step-relative), I received a nearly two-foot long, vintage panoramic photograph (known as a yardlong photo due to their length: these images can be nearly thee feet in length) of a U.S. Navy crew, professionally positioned and posed pier-side in front of their destroyer.

Finding this framed yardlong photo was a pleasant surprise. It took me a second or two to spot the lettering on the life-rings to know that this was my uncles’ ship. Moments later, I found them both, posed with their shipmates.

For the first half of the 20th Century, a common practice within the military was to capture, in photographs, an entire company, regiment, even battalion of soldiers. The same holds true with the compliment of naval vessels with divisions, departments or even the full crew (obviously, size of the ship and on-duty personnel dictate who is present in a photo). The photographs were taken with cameras that allow the lens to be pivoted or panned from side to side in order to span the entire width of the subject, exposing a very large piece of film. As with the negative, the resulting images were elongated and fairly detailed (most often, these were contact prints, the same size as the negative). However the extremities of the photographs were slightly distorted or lacking in crisp lines due to the chromatic aberration that is almost unavoidable. For the most part, the elongated images are quite detailed and almost without exception, faces are recognizable when the military units were captured within these yardlong photographs. There are still photographers creating panoramic images using vintage cameras and film.

- While visiting the USAF Airman Heritage Museum at Lackland AFB this past summer, I snapped some photos of this 1947 yardlong of the Air Training Command formation of the USAF insignia.

- This image shows the how the command used different uniforms and headgear to form the details of the insignia.

- Moving in closer to the photo, one can see the facial details of the airmen. The caption reads, “Indoctrination Division, Air Training Command, Lackland Air Base, San Antonio, Texas July 19, 1947.

The photograph that I received was in an old frame, backed with corrugated cardboard and pressed against the glass pane. As I inspected the image, I noticed the ship in the background behind the crew that was posed in their dress white uniforms. Noting the blue flaps and cuffs on the enlisted jumpers, I knew that the photo was taken in the 1930s. My eyes were drawn to the two life-rings that were held by sailors on each end of the image, displaying the name of the ship; USS Smith and the hull number, 378. From researching my paternal grandmother’s siblings, I discovered that both of her brothers had served in the U.S. Navy and were both plankowners of the Mahan-class destroyer, USS Smith (DD-378). Dating the image will take a little bit of work (there are no indications of when it was taken – not in the photographer’s marks on either corner nor written on the back). However, I do know when the ship was commissioned, when my uncles reported aboard and departed the ship. Discernible in the image on my uncles’ uniforms are some indications of rank. I can tell that the older brother (who enlisted in 1932) is a petty officer (he reported aboard as a Seaman 1/c) and the younger brother was still a seaman (I can’t see the cuffs of his uniform to determine the number of white piping stripes present) as noted by the blue cord on his right shoulder. I should be able to narrow down the period once I can go through the massive service records to locate dates of rank. However, my initial assessment is that the photo might have been captured near the time of commissioning or, perhaps to commemorate a change of commanding officers.

This yardlong image (a scan and a reproduction print) was sent to me by the son a of a veteran who served aboard the USS Vincennes (CL-64) during WWII.

This image was shot using a panoramic camera though it technically isn’t a yardlong photograph. The crew of the USS Vincennes (CA-44) is posed on the ship’s fantail, after 8″ turret and superstructure which is a nod to how many naval crew photos were posed in the late 19th Century.

Being an archivist for my ship and the recipient of some fantastic artifacts, I have been contacted by folks seeking to provide me with images to preserve within my photo archive. A few years ago, a gentleman emailed requesting to send to me a copy of a yardlong photograph that his father, a WWII navy veteran, owned from his time in service. The image was of the second cruiser (USS Vincennes) that was named for the city in Southwestern Indiana. The Cleveland-class light cruiser, hull number 64, had been laid down as the USS Flint but was changed during construction following the loss of the heavy cruiser during the Battle of Savo Island on August 8-9, 1942. The light cruiser was completed and commissioned on January 21, 1944 and served gallantly through WWII and was decommissioned in September of 1946. The man who contacted me had the ship’s photo scanned at a high resolution and sent the image file to me (on a thumb-drive along with a full-size print).

I wish I could have landed this photo of the USS Tacoma (CL-20) crew from 1920, four years before her demise on Blanquilla Reef, Vera Cruz, Mexico.

I am not a collector of yardlong photography but when the images are contextual to the areas that I do collect, I am happy to be able to acquire them. Receiving the image of the Smith and finding my grandmother’s brothers in the photograph motivated me to promptly hang it with my other family military history. In scanning the image for this article, I am reminded that I need to have it properly framed with archival materials to allow it to be preserved for generations to come.

Lumbering Along: Collecting C.E.F. Forestry Militaria

Inside a World War I trench showing the lumber shoring and the mud at floor. Duckboards at the bottom of the trench were intended to keep the soldiers’ feet out of the mud.

As a collector of militaria, I tend to fixate my thoughts on those pieces that pertain to combat or combat personnel, such as their uniforms and weaponry. With my specific area of interest—those in my family and ancestry who served in uniform in the armed forces—collecting items to recreate representations for these people has been relatively simple. My passion for history and knowledge of the United States military provides me with a leg up in the pursuit of knowledge and the nuances of the required research. As I pursue certain branches of my family tree, I am required to depart from this American-centric comfort zone as I head toward the land of the unknown: the Canadian and British military forces.

An example of a WWI Forestry Corps recruiting poster. Note the maple leaf emblem at the bottom of the poster, which is a close resemblance to the Forestry Corps collar devices in this article.

While conducting some scant research on a few relatives, I discovered that one of them, a Scot, served with the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment of Foot (which would later become the Black Watch) in the Americas during the War of 1812, as I mentioned in my piece, The Obscure War – Collecting the War of 1812. This ancestor, as well as his father (who also served in the same Scottish regiment), fought for what I would deem as the “enemy.” Once I got past that distinction, I was able to continue researching, setting aside any biases.

In researching more immediate family members along the same British family lines (see my previous post, I am an American Veteran with Canadian Military Heritage), I discovered that my great, great-grandfather answered his nation’s call to serve against Imperial Germany in what would be known as the War to End All Wars. At his “advanced” age of 47 and a recent widower, my ancestor could have elected to abstain from service (the Military Service Act, 1917 required service of men aged 18-41), yet he felt compelled to serve in some capacity. Like many Canadians who would otherwise have been ineligible for military duty due to age or physical limitations, and who served in other support-based, non-combatant, units, my great, great-grandfather joined the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (C.E.F.) Forestry Battalion.

With the insatiable demand for lumber to be utilized at the war front (for trench walls and shoring, duckboards, crates, containers and building construction), the British government called upon the experienced woodsmen of North America to begin to harvest the seemingly unending forests of Canada. Desiring expediency in the supply chain between the lumbermen and the front, combined with the demand to utilize the invaluable cargo space aboard the merchant vessels for other needs, the military leaders determined that by bringing the Forestry Corps troops to Europe to harvest timber in the forests of the UK and France would better serve the needs of the front line troops.

Forestry Corps troops ply their skills on Scottish timber, 1917 (source: Heritage Society Grand Falls-Windsor, Newfoundland).

Between 1916 and the signing of the Armistice, some 31,000 men served with the C.E.F. Forestry Corps in Canada and Europe. During that period, the Forestry Corps produced nearly 814,000,000 feet board measure of sawn wood plus 1,114,000 tons of other wood products. Though he probably never picked up a weapon (some units were close enough to the front and were required to be prepared to be used as reserve troops), my great, great grandfather served in an invaluable capacity risking life and limb for the war effort.

As with all of my collecting efforts, I am continuously seeking to document and locate artifacts that can be assembled to form representative displays for the many veterans in my family’s history. With regard to my great, great grandfather, I have only begun to scratch the surface in researching the uniforms of the Forestry Corps and what he might have worn along with any decorations he might have earned.

- I located this pair of C.E.F. Forestry Corps collar devices after a rather lengthy search. Their maple leaf and beaver-clad design belie the wearer’s role in the Expeditionary Force (source: eBay image).

- These 230th Forestry Corps Devices are incomplete as the one on the left is missing the cotter retention pin, which wasn’t a deal-breaker for my display (source: eBay image).

A few years ago, I managed to locate a pair of collar devices that are specific to his unit, the 230th Forestry Battalion. Being that my focus has been with U.S. militaria, I’ve gained an appreciation for the beauty of the Canadian and British uniform appointments. In examining the devices, one can quickly see the Canadian heritage in the maple leaf design. Along with the Forestry Corps word-mark, there is a beaver on the crest to punctuate the principal function of the unit. Superimposed across the front is the battalion designation, clearly identifying to which military unit the wearer belongs to.

Putting the devices together, they are a start for what could be a nice display.

Not too long after locating the collar devices, an auction for the matching hat device was listed and I was the subsequent highest bidder. With three pieces, I started watching for other items that would display well in a small shadow box of items representing my great-great grandfather’s service. Searching for such hard to find items as Canadian Forestry Corps pieces requires patience. I am not sure exactly how far I will go in the pursuit of assembling this Forestry Corps display as the pieces are sparse and difficult to find when compared to U.S. pieces of the same era. It might be quite costly to put together the even most minimalistic grouping of items which may force me to quit with what I have today.

Like my other ongoing projects, this one could last the span of several years. More so than funds, I have the time to wait for the right pieces!

See also:

I am an American Veteran with Canadian Military Heritage

Interested in European Military Headgear?

One of the most exciting aspects of militaria collecting for me is when I can locate an item that can be connected to one of my family members’ military service. To date, I have predominantly made those connections with my ancestors who served in the United States Armed Forces. However, when I started searching for relevant militaria pieces (that would be relevant to my Canadian or British veteran ancestors), I discovered that if I had deep enough pockets, there would have been an opportunity to obtain something that could be associated with my 4th great-grandfather who served with the legendary 42nd Highland Regiment of Foot, The Black Watch.

With the research that I’ve conducted during the last several years, I’ve been focusing on those of my ancestors with military service. I’ve been following each branch of the tree, tracing back through each generation, some of which first reached the colonial shores in the late 1600s from Western Europe. Without boring you with the details, I have been successful in locating ancestors who served and fought in almost every war since the establishment of the colonies, including the French and Indian War.

As a veteran of the US Navy, my interest has been centered on those of my ancestors who wore the uniform of the United States. What I didn’t count on was finding veterans who fought for what my American ancestors would have called “the enemy.” One ancestor in particular was a member of one of the elite British units (which is still in existence) and fought against the forces of the US during the War of 1812. I discovered that still another of my American ancestors was taken prisoner by the British and actually met the enemy ancestor (I know, this sounds confusing).

During one of my subsequent militaria searches, I discovered an online auction house that had a listing for foreign military headgear that were some of the most beautifully pristine pieces I have ever seen. Not being educated in foreign militaria, I was caught up in the aesthetic aspects of each piece while I was almost completely ignorant as to authenticity, time period of use, or even the military history of the piece. But one lot in particular caught my attention.

This feather bonnet and glengarry cap of the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment of Foot is in pristine condition. It, along with dozens of other foreign military headgear pieces will be available at auction in early September (source: Rock Island Auction Company).

Prominently displayed as part of the group was an Officer’s Feather Bonnet and Glengarry Cap that was from 42nd Highland Regiment of Foot, The Black Watch, the unit which dates back to the early 18th century. Both headpieces featured ornate badges with the unit number prominently emblazoned at the center of the design. The condition of the hats were so spectacular that they appeared to be recent manufacture, however the quality of the items spoke to their age.

As I read the auction description, disappointment soon set in as I learned that the cap dated to 1885 and the bonnet was from the turn of the 20th century, probably from 1900. Any disappointment that I may have felt in learning of the relative recency of the pieces was assuaged by the reality that the lot probably sold for a price that is unrealistic for my budget (I didn’t bother following it through the auction close). It is okay to dream every once in a while, isn’t it?

Before I can start investing in anything from the 18th and 19th centuries, I need to spend a lot of time and resources solidifying my research on my ancestors.

I also need to start playing the lottery.

The Obscure War – Collecting the War of 1812

One of my hobbies – truth be told, it is more than just a hobby for me – is genealogy research. Specifically, I am interested in uncovering facts and details pertaining to those of my ancestors who served in combat or just in uniform for this country. As with any research project, each piece of verifiable data opens the door for new, deeper research. One thing I haven’t been able to do is to find a stopping point once that occurs.

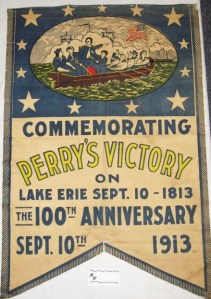

This banner depicts Commodore Perry in a long boat with enlisted sailors. Banner was produced as part of the Centennial celebration of the War of 1812 (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

Due to the recency of that time period, researching veterans who served in the twentieth century may seem to be an easy task when one considers the sheer volume of paperwork that can be created for or associated with an individual service member. If one has the time and resources available, it can be relatively easy to obtain all the records connecting a soldier, sailor, airman or marine to every aspect of their service during World War II or Korea. However, this becomes increasingly difficult as you seek details for those who served in earlier times.

Booms in militaria markets occur around significant anniversaries which propel history enthusiasts into seeking artifacts and objects from these events. On April 2, 2017, the United States began to mark the centennial of her entry into WW1 (the date is the anniversary of President Wilson’s request to Congress for a formal declaration of war against Germany) which has ignited an interest in WWI militaria by existing and new militaria seekers, alike resulting in a significant spike in prices. The renewed interest is a repeat of another of the United States’ conflicts that occurred just a few years ago.

During 2012, several states and the U.S. Navy initiated commemorating the bicentennial of the War of 1812 (formally declared by Congress on June 18, 1812) and the year-long recognition of this monumental conflict between the United States and Great Britain. This war has seemingly been a mere footnote when taught in American schools, exceedingly overshadowed by the War for Independence or the War between the States, and very little documentation is available for research when compared to other more popular conflicts.

- Wooden box carved from the keel of the brig Siren (Syren), by C.H. Holst in 1855. The Syren was one of the first brigs built for the U.S Navy in 1803 at Philadelphia by Nathaniel Hutton. The Syren participated in the Barbary War, and the War of 1812. The ship changed her name to Siren in 1810. (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

- Wooden box carved from the keel of the brig Siren (Syren), by C.H. Holst in 1855. The Syren was one of the first brigs built for the U.S Navy in 1803 at Philadelphia by Nathaniel Hutton. The Syren participated in the Barbary War, and the War of 1812. The ship changed her name to Siren in 1810 (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

My ancestral history has confirmed that several lines in my family are early settlers of what became the United States. So far, I have been able to locate documentation verifying that three of my ancestors fought in support of the struggle for Independence. Several generations downstream from them shows an even more significant amount of family taking up arms during the Civil War. The documentation that is available in print and online is incredible when it comes to researching either of these two wars. But what about the conflicts in between – the War of 1812 in particular?

- Walking cane made from ivory and wood. The wood used to make this cane was salvaged from the USS Lawrence flag ship of Commodore Perry in 1840. The ship had been scuttled at the end of the war in Misery Bay Presque Isle PA (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

- A close-up of the USS Lawrence walking cane’s inscription plate (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

- This sword was presented to Lt. Thomas Holdup Stevens by the city of Charleston for his conduct during the Battle of Lake Erie on the 10th of September 1813. Stevens commanded the sloop Trippe and engaged in battle with the Queen Charlotte. The Trippe also assisted the Scorpion in pursuing and capturing two enemy vessels (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

- A close-up of the handle, grip and hilt of LT Thomas Holdup Stevens’ Sword (source: Collection of Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command).

By chance, I was able to locate two veterans (family members) who fought in this 32-month long war with England. The strange thing about it is that one fought for the “enemy” and the other for the United States. Even more strange was that they met on the field of battle with the American being taken captive and subsequently guarded by the British soldier. At some point, the two became more than cordial enemies and the American POW’s escape was benefited by that friendship. Years later, the two veterans would meet (after the British veteran immigrated to North America) and the one-time adversaries would become neighbors. The American veteran would ultimately marry the former Brit’s daughter, forever linking the two families.

One of the pistols used by William Henry Harrison during his service in the War of 1812.

While researching the War of 1812 can be difficult for genealogists, collecting authentic militaria of the conflict poses an even greater challenge. Very little remains in existence and, of that, even less is in private hands making it next to impossible for individual collectors to obtain without paying exorbitant prices or being taken by unscrupulous sellers (or both).

To say that uniforms from the period are scarce is putting it very mildly. The ravages of time exact their toll on the natural fibers of the cloth (wool, cotton) and the suppleness of leather, making anything that survived to present day an extremely delicate item. Hardware such as buttons and buckles are more likely to be available and while less expensive than a tunic or uniform, they will still be somewhat pricey.

I have resigned myself to the idea that owning any militaria item from the first 100 years of our nation’s existence is out of the question choosing instead to marvel at the collections that are available within the confines of museums.