Blog Archives

Researching After You Buy – Sometimes it is the Better Option

I’ve said it so many times in the past: it is paramount to making wise purchases that collectors research an item prior to handing over hard-earned finances to make a purchase. However, there are occasions within militaria collecting where the collector is stumped by what he or she might be looking at, yet still feel compelled to pull the trigger on a deal to acquire it.

Recently, a very dear friend and fellow collector presented me one of his most recent acquisitions and wanted to get my input as to the markings and what they might indicate. He was stumped by some of the heraldry and details but there were other engraved elements that showed the piece to be from World War I.

The dates of 1914, 15, 16 and 17 automatically rule out this matchbox as being a U.S. trench art piece.

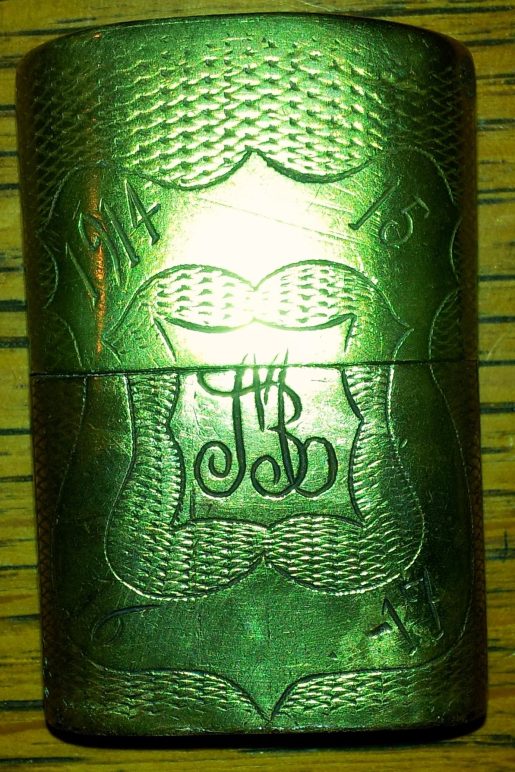

I spent several minutes examining what appeared to be a trench art matchbox. Clearly, the item shown is constructed from brass and was handmade. The brass plates were rolled out and soldered together to form an oblong can-shape with another piece cut and soldered into place at the top. A piece of wood was shaped and fastened to comprise the case’s bottom, and adhered with some sort of clear glue or shellac. Judging from the length of the box, the brass was an unrolled and flattened small arms casings, a very common resource used in trench art making.

What does the crescent and “winged Z” indicate? The hand-tooling is quite ornate and aesthetically pleasing. I’d say that this was a solid score for my friend.

On one side, the maker tooled a pattern and left a smooth shield motif with what appears to be a monogram of the initials, “MB.” At the surrounding corners of the shield are “1914”,” 15”, “16” and “17” which clearly indicates the first few years of World War I.

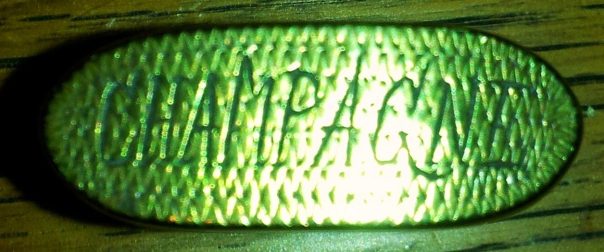

Etched into the opposing side of the matchbox is what appears to be a crescent or “C” with the opening pointed upward. Inside the crescent are two wings – one, at the bottom, pointing to the left with the top one pointing to the right. Connecting the two wing tips is a heavy line running diagonally, right to left from the top to the bottom. All three pieces appear to form the letter “Z.” Superimposed over the diagonal line is a small numeral two. Over the top of this “winged Z” is appears the year, “1917.” To the top right is a star with radiant beams extending outward to all directions providing a backdrop design. The top panel is etched simply etched with “Champagne”, surrounded by tooled pattern.

The matchbox top has “Champagne” engraved. To me, this clearly indicates that the owner spent a good portion of WWI serving in these battles.

I knew that the piece was from WWI and was potentially French or British in origin (it could even be German) due to the dates of the piece, as the U.S. didn’t enter the war until 1917. Could the crescent indicate Arabic or Islamic participation? Could it be connected to the French Foreign Legion? Does “Champagne” refer to the battles that were fought in 1914, 1915, 1916 and 1917?

Due to the sheer beauty of this piece, it has proven to be a very wise investment my friend made (at least in my opinion) regardless of his lack of certainty about it. This matchbox will be a fun and interesting research project. Perhaps one of you recognizes the emblems or has any ideas? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Lumbering Along: Collecting C.E.F. Forestry Militaria

Inside a World War I trench showing the lumber shoring and the mud at floor. Duckboards at the bottom of the trench were intended to keep the soldiers’ feet out of the mud.

As a collector of militaria, I tend to fixate my thoughts on those pieces that pertain to combat or combat personnel, such as their uniforms and weaponry. With my specific area of interest—those in my family and ancestry who served in uniform in the armed forces—collecting items to recreate representations for these people has been relatively simple. My passion for history and knowledge of the United States military provides me with a leg up in the pursuit of knowledge and the nuances of the required research. As I pursue certain branches of my family tree, I am required to depart from this American-centric comfort zone as I head toward the land of the unknown: the Canadian and British military forces.

An example of a WWI Forestry Corps recruiting poster. Note the maple leaf emblem at the bottom of the poster, which is a close resemblance to the Forestry Corps collar devices in this article.

While conducting some scant research on a few relatives, I discovered that one of them, a Scot, served with the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment of Foot (which would later become the Black Watch) in the Americas during the War of 1812, as I mentioned in my piece, The Obscure War – Collecting the War of 1812. This ancestor, as well as his father (who also served in the same Scottish regiment), fought for what I would deem as the “enemy.” Once I got past that distinction, I was able to continue researching, setting aside any biases.

In researching more immediate family members along the same British family lines (see my previous post, I am an American Veteran with Canadian Military Heritage), I discovered that my great, great-grandfather answered his nation’s call to serve against Imperial Germany in what would be known as the War to End All Wars. At his “advanced” age of 47 and a recent widower, my ancestor could have elected to abstain from service (the Military Service Act, 1917 required service of men aged 18-41), yet he felt compelled to serve in some capacity. Like many Canadians who would otherwise have been ineligible for military duty due to age or physical limitations, and who served in other support-based, non-combatant, units, my great, great-grandfather joined the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (C.E.F.) Forestry Battalion.

With the insatiable demand for lumber to be utilized at the war front (for trench walls and shoring, duckboards, crates, containers and building construction), the British government called upon the experienced woodsmen of North America to begin to harvest the seemingly unending forests of Canada. Desiring expediency in the supply chain between the lumbermen and the front, combined with the demand to utilize the invaluable cargo space aboard the merchant vessels for other needs, the military leaders determined that by bringing the Forestry Corps troops to Europe to harvest timber in the forests of the UK and France would better serve the needs of the front line troops.

Forestry Corps troops ply their skills on Scottish timber, 1917 (source: Heritage Society Grand Falls-Windsor, Newfoundland).

Between 1916 and the signing of the Armistice, some 31,000 men served with the C.E.F. Forestry Corps in Canada and Europe. During that period, the Forestry Corps produced nearly 814,000,000 feet board measure of sawn wood plus 1,114,000 tons of other wood products. Though he probably never picked up a weapon (some units were close enough to the front and were required to be prepared to be used as reserve troops), my great, great grandfather served in an invaluable capacity risking life and limb for the war effort.

As with all of my collecting efforts, I am continuously seeking to document and locate artifacts that can be assembled to form representative displays for the many veterans in my family’s history. With regard to my great, great grandfather, I have only begun to scratch the surface in researching the uniforms of the Forestry Corps and what he might have worn along with any decorations he might have earned.

- I located this pair of C.E.F. Forestry Corps collar devices after a rather lengthy search. Their maple leaf and beaver-clad design belie the wearer’s role in the Expeditionary Force (source: eBay image).

- These 230th Forestry Corps Devices are incomplete as the one on the left is missing the cotter retention pin, which wasn’t a deal-breaker for my display (source: eBay image).

A few years ago, I managed to locate a pair of collar devices that are specific to his unit, the 230th Forestry Battalion. Being that my focus has been with U.S. militaria, I’ve gained an appreciation for the beauty of the Canadian and British uniform appointments. In examining the devices, one can quickly see the Canadian heritage in the maple leaf design. Along with the Forestry Corps word-mark, there is a beaver on the crest to punctuate the principal function of the unit. Superimposed across the front is the battalion designation, clearly identifying to which military unit the wearer belongs to.

Putting the devices together, they are a start for what could be a nice display.

Not too long after locating the collar devices, an auction for the matching hat device was listed and I was the subsequent highest bidder. With three pieces, I started watching for other items that would display well in a small shadow box of items representing my great-great grandfather’s service. Searching for such hard to find items as Canadian Forestry Corps pieces requires patience. I am not sure exactly how far I will go in the pursuit of assembling this Forestry Corps display as the pieces are sparse and difficult to find when compared to U.S. pieces of the same era. It might be quite costly to put together the even most minimalistic grouping of items which may force me to quit with what I have today.

Like my other ongoing projects, this one could last the span of several years. More so than funds, I have the time to wait for the right pieces!

See also:

I am an American Veteran with Canadian Military Heritage

Consistency through Change – The U.S. Army Uniform

This uniform, though an immediate post-Civil War-issue, is clearly that of a sergeant in the U.S. Cavalry as noted by the gold chevrons (hand-tinted in the photo).

Over the weekend leading up to Independence Day, I had been inspired by my family military service research project, which had me neck-deep in the American Civil War, which caused me to drag out a few DVDs for the sheer joy of watching history portrayed on the screen. Since the Fourth of July was coming up, I wanted to be sure to view director Ronald Maxwell’s 1993 film Gettysburg, on or near the anniversary of the battle, which took place on July 1-3, 1863.

I had watched these films (including Gods and Generals and Glory) countless times in the past, but this weekend, I employed more scrutiny while looking at the uniforms and other details. Paying particular attention to the fabrics of the uniforms, I was observing the variations for the different functions (such as artillerymen, cavalrymen, and infantry) while noting how the field commanders could observe from vantage points where these regiments were positioned, making any needed adjustments to counter the opponents’ movements or alignments. For those commanders, visual observations from afar were imperative and the uniforms (and regimental colors/flags) were mandatory to facilitate good decision making.

The tactics employed for the majority of the Civil War were largely carryovers from previous conflicts and had not kept pace with the advancement of the weaponry. Armies were still arranged in battle lines facing off with the enemy at very close range (the blue of the Union and the gray of the Confederacy), before the commands were given to open fire with the rifles and side arms. The projectile technology and barrel rifling present in the almost all of the infantry firearms meant that a significantly higher percentage of the bullets would strike the targets. In prior conflicts where smooth-bore muskets and round-ball projectiles were the norm, hitting the target was met with far less success.

The uniforms of the Civil War had also seen some advancement as they departed from the highly stylized affairs of the Revolution to a more functional design. In the years following the war, uniform designs saw some minor alterations through the Indian Wars and into the Spanish American War. By World War I, concealment and camouflaging the troops started to become a consideration of military leadership. Gone were the colorful fabrics, exchanged for olive drab (OD) green. By World War II, camo patterns began to emerge in combat uniforms for the army and marines, though they wouldn’t be fully available for all combat uniforms until the late 1970s.

Though these uniforms have a classy appearance, they were designed for and used in combat. Their OD green color was the precursor to camouflage.

This World War II-era USMC combat uniform top was made between 1942 and 1944. Note the reversible camo pattern can be seen inside the collar (source: GIJive).

For collectors, these pattern camouflage combat uniforms are some of the most highly sought items due to their scarcity and aesthetics. The units who wore the camo in WWII through the Viet Nam War tended to be more elite or highly specialized as their function dictated even better concealment than was afforded with the OD uniforms worn by regular troops.

Fast-forward to the present-day armed forces, where camouflage is now commonplace among all branches. The Navy, in 2007-2008, was the last to employ camo, a combination of varying shades of blue, for their utility uniforms citing the concealment benefits (of shipboard dirt and grime) the pattern affords sailors. All of the services have adopted the digital or pixellated camo that is either a direct-use or derivative of the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) first employed (by the U.S.) with the Marine Corps when it debuted in 2002. Since then, collectors have been scouring the thrift and surplus shops, seeking to gather every digital camo uniform style along with like-patterned field gear and equipment.

The first of the U.S. Armed Forces to employ digital camouflage, the USMC was able to demonstrate successful concealment of their ranks in all combat theaters. Shown are the two variations, “Desert” on the left and “Woodland” on the right.

After a very limited testing cycle and what appeared to be a rush to get their own digital camo pattern, the U.S. Army rolled out their ACU or Army Combat Uniform with troops that were deploying to Iraq in 2005. With nearly $5 billion (yes, that is a “B”) in outfitting their troops with uniforms, the army brass announced this week that they are abandoning the ACU for a different pattern citing poor concealment performance and ineffectiveness across all combat environments. With the news of the change, the army has decided upon the replacement pattern, known as MultiCam, which has already been in use exclusively in the Afghanistan theater.

After a very limited testing cycle and what appeared to be a rush to get their own digital camo pattern, the U.S. Army rolled out their ACU or Army Combat Uniform with troops that were deploying to Iraq in 2005. With nearly $5 billion (yes, that is a “B”) in outfitting their troops with uniforms, the army brass announced this week that they are abandoning the ACU for a different pattern citing poor concealment performance and ineffectiveness across all combat environments. With the news of the change, the army has decided upon the replacement pattern, known as MultiCam, which has already been in use exclusively in the Afghanistan theater.

For collectors of MultiCam, this could be both a boon (making the items abundantly available) and a detractor (the limited pattern was more difficult to obtain which tended to drive the prices up with the significant demand). For those who pursue ACU, it could take decades for prices to start climbing which means that stockpiling these uniforms could be a waste of time and resources. Only time will tell.

Since the Civil War, the U.S. Army uniform has one very consistent aspect that soldiers and collectors alike can hang their hat upon…change.

Sound Timing and Patience Pays Off

I am a sucker for U.S. naval history. There, I said it. I love it all from John Paul Jones and the USS Ranger to the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), the lead ship in the newest class of aircraft carriers, I can’t get enough. My tendencies and preferences seem to take me to more contextual aspects of naval history – anything to do with the geographical region of my birth holds my interests (unless, of course it is connected to the ships or commands where I served).

I seek out items that can be associated with ships named for geographic locations (city names, place names, etcetera), pieces that can be connected to the local naval installations or anything that originates with local naval figures, such as the Rear Admiral Robert Copeland group in this earlier post. To date, the majority of these items have been vintage photographs…until yesterday.

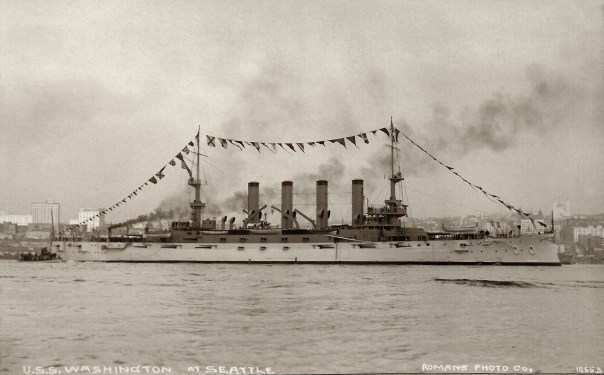

Prior to her reclassification, the (then) USS Washington (ACR-11) rests at anchor near her future namesake, Seattle, WA (author’s collections).

While searching online, I stumbled across a listing that contained a piece of history that made my jaw drop. To see the price was so much lower than it should have been made me giddier than a kid on Christmas morning. I placed my watch on the item and planned observe it for a few days to see if any bids were placed. A few days later, with no one bidding (that I knew of) I configured my bid snipe and hoped that all would work out.

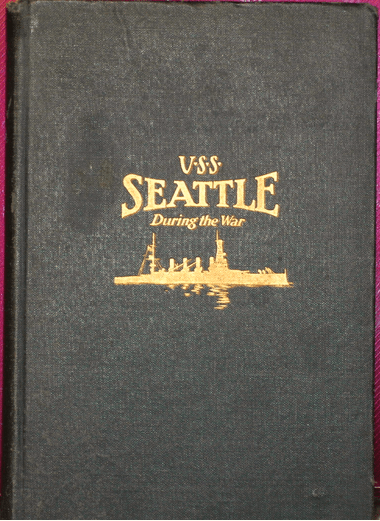

Judging from the auction listing photo, the cover of my new vintage cruise book is in nearly pristine condition (source: eBay image).

Around the time of the auction close, I was out and about when I received an email that my sniped bid was the winner and that no other parties had bid against me, leaving the closing price the minimum amount. The item, a World War I cruise book from the USS Seattle (an armored cruiser of the Tennessee class) that was placed into commission in 1906, documents the ship’s WWI service during the war, serving as a convoy escort as she provided merchant vessels protection from German U-boats during trans-Atlantic crossings to the United Kingdom.

- The inside end papers is inscribed with what appears to be the previous owner’s name – who was a coxswain aboard the ship. I will be researching the sailor’s name to see what I can learn about him (source: eBay image).

- Inside the pages of the book, this photo shows the USS Seattle in her “dazzle” camouflage paint scheme (source: eBay image).

As cruise books were produced in small numbers (for the crew), they are quite rare typically driving the prices close to, and sometimes surpassing, $500. Like most vintage books, condition is a contributing factor in the value. My USS Seattle book was available at a fraction of these prices making it affordable when it would normally have been well out of my budget.

Good things come to those who wait…and who check at the right time. For me, the waiting continued right up until the time that I tore into the package moments after it was delivered by the letter carrier (yes, I can behave as a child, still).

I am an American Veteran with Canadian Military Heritage

I’ve been revisiting my family tree research, spurred on by catching up on watching episodes of The Learning Channel’s Who Do You Think You Are? (WDYTYA) The show follows a pretty simplistic theme of tracing some Hollywood notable’s ancestral history as they have been suddenly overcome with desire to know where they came from. There is always some sort of misplaced desire for self-validation as they seek to identify with the very real struggles that someone in their family tree endured centuries ago. In watching them I often find the humor as the celebrity emotionally aligns with a nine or ten times great grandparent as if that person were an active part of their life. Where the humor in this originates is that one must consider exactly how many great grandparents one has at this particular point in our ancestry.

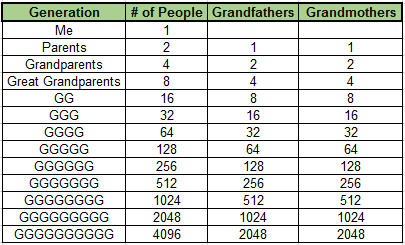

My 3x great grandfather (one of sixteen such 3x great grandfathers) served with the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry during the American Civil War) and like the Hollywood celebrities on WDYTYA, I have researched him extensively and I do identify with him. But consider that there are 15 other 3x great grandfathers along with eight 2x greats, four greats and two grandfathers. That means that five generations above me encompass 28 grandfathers including the lone Civil War veteran that I thoroughly researched. If viewed this prospective with another one of the great grandfathers (whom I researched and found to have served during the American Revolution), he would be one of 64 5x great grandfathers (for a total of 254 total grandfathers at this generation-level). This can get confusing to grasp without a visual:

When folks refer to their 7th great grandfather, what does that mean? Did they have more than one? The answer is that everyone has 256 7th great grandfathers. It is simple math, folks!

There are a few other pieces that I have for the display that I am assembling, including a section of vintage ribbon for the service medal. The shoulder tabs are a more recent acquisition as is the CFC hat badge (bottom left) that my 2x great grandfather wore prior to being assigned to the 230th. The two smaller insignia flanking the medal were worn on the uniform collar. The pin on the lower right was a veteran’s organization pin.

I have been gathering artifacts together to create representations of some of my ancestors with military service. I have been sporadically researching as many relatives as I can locate to document a historical narrative of service by members of my family. This is a daunting task considering how many direct ancestors I have and I have been also including some uncles and cousins as I uncover them. One of my 2x great grandfathers (one of 8 such great grandfathers) was a British citizen who emigrated to Victoria, British Columbia with his wife and ten children a few years following the turn of the twentieth century. By the time the Great War broke out in Europe in 1914, he was a 45-year-old carpenter and home builder. When he was drafted into the Forestry Corps of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in June of 1916, he was 47 and a widower. He served in Europe for the duration of the war harvesting timber for use in the war effort, plying his carpentry skills in some fashion being far too old for combat duty.

Having a Canadian veteran ancestor (one of two – I wrote about the other one, previously) posed some challenges in researching his service as nearly every aspect of research is different from what I am familiar with (with American military records). Learning the terminology and the unit structure was difficult but even more challenging was deciphering my GG grandfather’s service records let alone locating details as to what his uniform insignia and devices would have been. Thanks to a few helpful CEF sites and forums, I was able to piece together some of the principle elements in order to assemble a shadow box at some point in the future.

This is a simple, yet tasteful display of a veteran of the 230th Canadian Forestry Corps from WWI. This soldier was in the same unit as my 2x great grandfather.

As any Canadian militaria collector could tell you, locating pieces from individual regiments/units of the Forestry Corps can be daunting. When I started on this path a few years ago, the prices were higher than those of American units by as much as three times. Collar and cap devices and badges were can reach prices beyond $40-50 (collar) and $70-100 (for caps badges). Not that ever intended to purchase actual uniforms pieces (tunic, cap, hat, etc.), I still maintained a watchful eye just to see what might show up for sale. Today, my eyes were enlarged and mouth left agape when something appeared in my automated search for such items.

Listed yesterday on eBay was a 1917-dated British trench hat that is in impeccable condition, complete with the badge of my 2x great-grandfather’s unit. Everything about this century-old cap seems to be in an incredible state – the hat’s shape, the leather sweatband – all of it. But then I saw the opening bid amount – $750.00 (in USD) – and immediately, my jaw struck my desktop beneath me! In the “People who viewed this item also viewed” section were British head covers (one trench hat and two visor caps) of comparable condition but with devices from other, non-Forestry units with prices that ranged from $500-700, depending upon the unit insignia. The hat from my ancestor’s unit topped the range of prices. Being in possession of the cap device, I wouldn’t need to pursue such an expensive purchase (I don’t need the hat for the display that I am assembling) so I will simply watch to see if the hat does end up finding a new home and take note of the selling price.

- This hat differs from the peak cap in that the top is slouched down over the sides and the bill is soft and stitched like a baseball cap. The 230th Canadian Forestry Corps device is centered over the leather chinstrap (eBay image).

- Showing the hat’s right side and the top of the visor (eBay image).

- The close up of the CFC badge – the insignia incorporates crossed pikes superimposed over a maple leaf with a long crosscut saw with a beaver (eBay image).

- The chinstrap button detail is impressive (eBay image).

- The high-level view of the hat’s underside (eBay image).

- These markings appear to be the maker’s mark, the hat’s size and the date of manufacture (eBay image).

- I am unfamiliar with these markings. I am sure that the experienced collectors and historians could easily provide some insight as to their meaning (eBay image).

- On the sweatband, the soldier’s initials and service number are hand-inscribed and provide an easy path for researching the original owner’s service (eBay image).

With just one of my maternal 2x great grandfathers with military service (albeit, British-Canadian) and none of my paternal 2x great grandfathers, I don’t have any more military artifacts left to gather for this particular generation (unless I am able to discover new facts for others). The preceding and following generations reveal that I have a lot of research effort in store for me not to mention what lies ahead for me within my wife’s equally extensive family military history.

See Also:

Lumbering Along: Collecting C.E.F. Forestry Militaria