Blog Archives

The Enigmatic pursuit of the Third Reich Encryption Machine

History is continuously subjected to revision as stories are told and retold. Researchers and historical experts are seemingly discovering previously hidden facts or secrets that shed new light on events. With the new revelations, previous facts surrounding historical events are skewed or changed causing a re-shaping of timelines and ultimately public perception. Hollywood however, seems bent on taking a different tack with regards to revising history in order to reshape producers’, directors’ and actors’ bank accounts.

This scene shows the disguised American sub (“S-33”) meeting with the U-571 in a rouse to obtain the Enigma code machine (source: Universal Pictures).

In April of 2000, Universal Pictures released a highly successful historical-fiction movie depicting the U.S. Navy’s successful capture of a Kriegsmarine u-boat during World War II. The premise of the film was centered on seizing the keystone encryption device (often referred to as Germany’s “secret weapon”), the Enigma encode/decoding machine along with the codes. While director Jonathan Mostow (who also co-wrote the screenplay) navigates around the historical truths by conveniently mentioning that the story is a compilation of actual events rather than being based on a true story. While this may have worked for American audiences, Great Britain’s Prime Minister (at the time of the film’s release), Tony Blair agreed with discussion (about the film) in Parliament that the story was an affront to the British sailors who gave their lives in the actual retrieval of the Enigma device during the war.

Rather than embarking on a mission to demonstrate the challenges created by Hollywood’s propensity of altering reality (albeit for entertainment purposes), I want to focus more on the capture of the machine and codes and what that meant for achieving an Allied victory over the Axis powers during World War II.

Prior to the United States’ entry into WWII on December 8, 1941, Europe had already been gripped with conflict for twenty-five months. Though it was a highly protected secret, the Allies were fully aware of the existence of the Enigma machine and had already seen successful code-breaking efforts (by the Polish Cipher Bureau in July of 1939) until continued German technological advances rendered those efforts obsolete. It wasn’t until May 9th, 1941 that the Allies achieved their most substantial breakthrough with the British capture of U-110 along with codes and other intelligence materials.

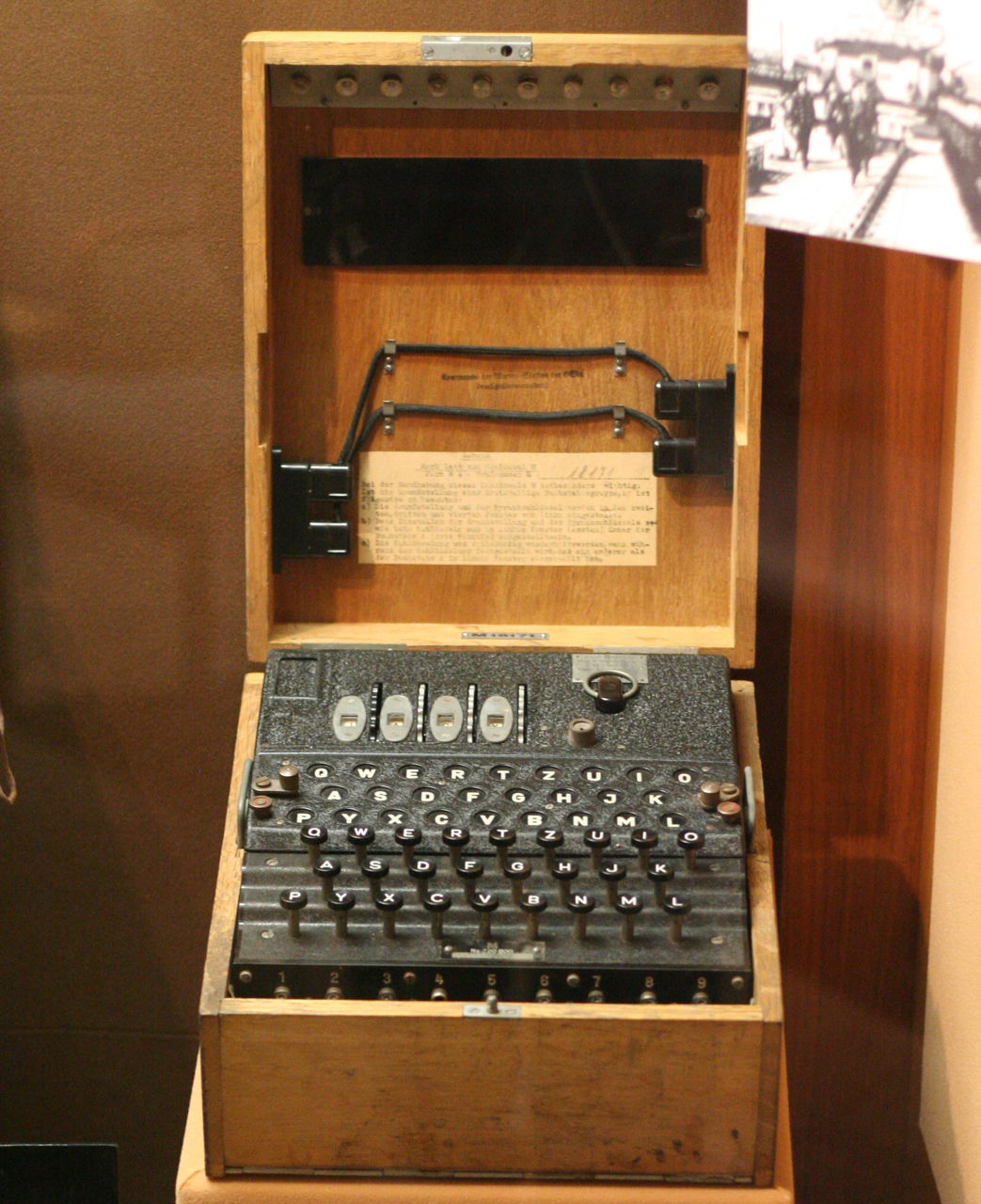

One of the events that is allegedly covered (by the U-571 film) is the United States’ capture of the U-505 in 1944 (three years after U-110) which was towed to Bermuda. Following the war, the U-boat was towed to Portsmouth Navy Yard, New Hampshire where she sat until being transported to Chicago to be displayed as a museum ship. The U-505 is now preserved inside the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Also on display are two Enigma code machines.

In addition to the two machines in the Chicago MOSI, there are a handful in museum collections around the globe. Due to the scarcity of the devices, their notoriety and the impact of their capture had on the outcome of the war, Enigmas command incredible premiums when they surface on the market. As recent as 2011, a Christies’ listing yielded a sale with the winning bid in excess of $200,000.

This Enigma’s selling price was in excess of $35,000 (US) when it was listed at auction in March of 2013 (source: eBay image).

Most recently, the winning bid for an online auction listing (for a three-disk Enigma) seemed to reflect a more modest price as it sold for “only” $35,103. One has to wonder why, in only two years, would there be such a considerable price disparity (obviously factoring model, variant, condition, etc.) between the two transactions. Perhaps the current state of the economy is at play? Maybe the collector or museum with deep pockets was eliminated from the market with their purchase in 2011? Perhaps the $200k selling price was an anomaly and this recent auction reflects a more realistic value?

Either way, the Enigma will remain…well…just that…an enigma with regards to my own collection and the possibility of ever possessing one.