I am kicking off a three-part series this week to focus on a hot-button militaria collector topic : re-purposing militaria artifacts for monetary gain. While the discussion can be category agnostic (meaning that it can be applied to virtually all areas of collecting rather than just militaria), I am focusing on this from the area of military memorabilia.

A desert camouflage bracelet for veterans from the VA with crisis support information imprinted on the inside surface.

Wrist bands. They are typically made from a rubbery, silicone-like substance and come in a range of colors from bright and flashy to muted and subdued with some even in camouflage patterns. They have messages embossed (actually molded into the material) that are intended to call attention to various causes and are used to market a company’s brand.

A trendy fashion statement made popular by Lance Armstrong’s LiveStrong charity, you have seen these wrist bands worn by everyone from celebrities, to colleagues, neighbors and even family members over the past half decade. You have probably worn or are wearing one at this very moment. I am sure that there are collectors who focus their attention on them.

In the true spirit of capitalism (which I enthusiastically subscribe to), a Navy veteran found a niche market and created a business called Bands for Arms (B4A) that manufactured and sold their own version – an evolutionary step, if you will – of the message-laden wrist band. Their company website described their products as a way to honor veterans and to help families (and supporters of the U.S. military) feel connected to service members and veterans.

Bands for Arms’ operating model was essentially taking donated U.S. military uniforms (mostly from veterans or their families), dismantling them and constructing wrist bands from the materials that in some way represent the intended message or sentiments of the wearer. I am not disparaging this company or the products they sell as I do find the bands rather intriguing – some are very tastefully designed. And who could find fault with their support (50% of all proceeds) of organizations such as USO Japan, Project Lifting Spirits and the Marine Toys for Tots Foundation?

So what does this have to do with militaria collecting you ask?

Recently, a thread on a popular militaria discussion board alerted collectors to an activity where historic uniforms, worn by veterans who served this nation for the cause of freedom, were donated to B4A as part of a special project, resulting is a special product line. Detailed on the B4A site was how the uniforms had been donated to them by the National WWII Museum (in New Orleans, LA) to create the new line of bracelets known as The Historic Bracelet Collection and 50% of the sales proceeds from this product line would subsequently be donated back to the museum. While the finished product is very well-made, the end result is that the historic uniforms are gone, along with the connection to history associated with the veteran who wore it.

This screen capture shows bracelets were made from uniforms donated by the National World War II Museum. (Source: BandsforArms.com)

For the non-collector, this action may not be an issue. However, it is gut-wrenching for militaria collectors and historians, and has caused them to question the ethical practices of the museum and how they manage their artifacts. The unrest centers around the idea of a museum having donated uniforms for this purpose : intentionally destroying historic artifacts that had been entrusted to them with the promise that they would be preserved and displayed in that museum.

The militaria collectors I’ve associated with take the trust between donors and museums very seriously. If prospective donors no longer have the expectation of proper handling and care of their artifacts, why would they entrust them to any museum? Considering this trust, militaria collectors reacted to the idea that an entity as highly regarded as the National World War II Museum would remove these uniforms from their collection and send them out to be dismembered (and I use this term to emphasize the emotion surrounding this concept) to generate revenue in support of operational cost.

Displayed in this screen capture are two bracelets and the uniforms that were destroyed to make them. (Source: BandsforArms.com)

The militaria discussion board posts raised questions surrounding the proper handling of donated artifacts and the apparent disregard for the widely accepted, industry standard, museum deaccessioning processes. What opened the floodgates of animosity toward both entities were statements posted on the B4A sites (which includes their Facebook page) acknowledging the museum for the donated uniforms, which was the catalyst to the creation of the History Collection.

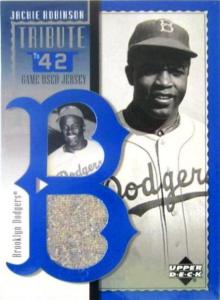

Frustrated collectors began posting their sentiments directly on the Facebook pages of both the National WWII museum and Bands for Arms, challenging the practice of dismantling historic artifacts (specifically, the WWII uniforms). B4A personnel responded by deleting any posts that called the B4A and National WWII Museum partnership into question.

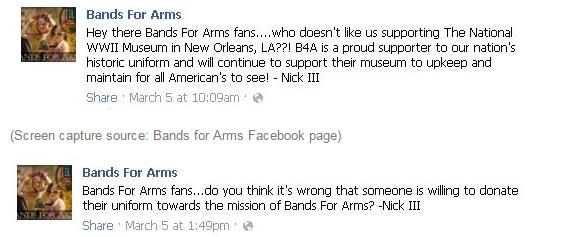

Bands for Arms personnel added comments to their Facebook page that appeared to mock the collectors with statements such as:

(Screen capture source: Bands for Arms Facebook page)

Over the span of a few days, B4A purged all evidence that referenced the uniform donation from the museum. The messaging on the (now defunct) B4A Historic Collection page had been carefully re-worded to describe the transaction more vaguely, between the ambiguously identified source of the uniform donations.

In stark contrast, the folks managing the Museum’s Facebook page began to directly address the collectors’ challenges openly while also requesting offline dialogue in order to fully explain the details of the transaction. A few of the responses demonstrate their positive actions:

- “We have been working to make sure all parties have the correct information and we are always available to respond to questions or concerns about the Museum.”

- “I would be happy to put you in touch with our registrar who can answer any questions you may have and share the details of our collections policy.”

Several collectors (at least one of which is a museum curator himself) did contact the museum directly and I know that a few had phone conversations with the staffer at the museum who was at the center of the transaction with Bands for Arms. The museum staffer also provided an e-mail response to inquiries regarding the issue:

“Thank you for your recent online inquiry regarding how the Museum cares for artifacts. I’d like to address your concern about a small number of items given to the Bands for Arms organization, but first want to explain our collections process. As you will see, we take very seriously our responsibility for handling artifacts in a professional and proper way.

Items donated to the Museum are considered for two major collections. The first is our Permanent Collection, which contains items that are rare and have a strong historical connection. The Museum always tries to link a military service member’s personal war experience to items donated by the individual or by family members.

The second major collection of the Museum is our Education Collection, which is used by several departments at the Museum for teaching activities. These activities include Living History Corps presentations, where presenters wear genuine World War II uniforms and gear for Museum visitors and students. Other selected items travel off-site under staff supervision for use with students and other interested groups. Educational uses do not preserve the life of the item long-term, but are instrumental in teaching World War II history.

Items that are dropped off at the Museum that do not meet the criteria for either the Permanent or Education Collection are typically returned to the donor. However, some donors do not wish to have items returned to them and the Museum makes these items available to other museums that may be able to use them. These items typically do not relate to the WWII period and have not been accepted into the Museum’s Permanent or Education collection.

When it has not been possible to return items to their original owner and no other institution is found to care for the items, we have utilized various methods to find another place for these pieces, including donation to local charities or other organizations. In 2010, after we were unable to return them to their owner and could not find another museum home for them, five uniform pieces—none from the WWII era—were given to Bands for Arms. These items did not qualify for inclusion in our collection. They are also the only items the Museum has provided to this organization. My personal connection is that I assist Bands for Arms in determining historical dates of uniforms they receive, a role that we play with many inquiring parties.

We currently house more than 140,000 items in our collection. While many items in the collection — including but not limited to Allied and Axis uniforms, weaponry, vehicles, medals, diaries, letters, artwork, photographs and other mementos — are on exhibit, the majority are kept safely in the Museum’s professional storage vault to be used for research and future exhibitions, or are being restored to their original condition.

The artifacts, documents, and personal accounts in the Museum’s Permanent and Education Collections are extremely important to the Museum’s mission of interpreting the American experience in WWII for current and future generations. In addition to carefully preserving these items, the Museum is embarking on a project to provide greater public access by improving our cataloguing and broadening our digitization of these items.”

Clearly, the museum is being responsive and professionally addressing the concerns head on, and I applaud them for these actions. As a novice historian, I still struggle with the destruction of the artifact, but I do understand the position the museum was in with regards to unwanted (at least by other museums or the donors) uniforms.

I know that the community of collectors are also satisfied with the museum’s responsiveness and willingness to be open about how they manage their collection. We are all hopeful that in the future, they will seek other avenues of artifact deaccession, avoiding destruction or disposal in order to continue to preserve our nation’s military history.

Shown here on an older Facebook post on the Bands for Arms page, references to the uniform donation by the National World War II Museum. These posts were subsequently removed.

What was difficult about the event was that Bands for Arms began a denial and suppression campaign when confronted by collectors who took issue with the uniform destruction. Instead of taking an above-board position by addressing the collectors’ concerns head on, they demonstrated a lack of maturity (and do not perceive this as an attack on B4A as I am not saying they behaved like children) that comes from having seasoned professionals managing external communications and messaging. I am betting that the leadership at B4A will use this event as a learning opportunity and will take note of the mistakes and missteps striving to not repeat them.

I’d also like to note that collectors do not take issue with B4A’s business model as they agree that veterans and family members may certainly do whatever they desire with their personal property. The folks at Bands for Arms do manufacture tasteful products and paying tribute to veterans while funding noteworthy veteran charities is quite admirable.

With the dust settling and the discussion posts winding down, is this the end of the debate? Do bracelets made from veterans’ uniforms truly honor them? As a collector, I have my own thoughts on this topic which will be the subject of the following segments in this series of posts.