Category Archives: World War II

USMC Patch Rarities and Scarcities – What to Look For

Admittedly, patch collecting has only been a dabbling affair for me. While I find this focus area quite intriguing and considerably broad, I still only give it contextual attention. What I mean by that is that I tend to acquire patches that are related or connected to something else I am already collecting. However, there are some exceptions that have lead me to dive a little deeper, assembling a little bit more of a complete collection of certain patches and shoulder sleeve insignia.

Being a veteran of the U.S. Navy, I find that I am more inclined toward navy and Marine Corps patches. Considering that Navy shoulder patches, predominantly seen during WWII, are limited to a handful of varieties, I have been slowly working to expand my collection with at least one example of each. Serious patch collectors know that each of these Navy patch types may have several variations in their design, embroidery, thread colors and backing materials, just to name a few. Rather than commit a lot of time and finances in the pursuit, I chose to simply fill the hole in the collection with one of the variations. My collecting of Marine Corps patches has followed the same path, but with the wider spectrum of patches, but building a complete group will require more time.

Time is something I have plenty of. World War II Marine Corps SSI run the gamut of availability and scarcity and unfortunately, more disposable cash is going to be required for me to fill the gaps in my collection as some USMC patches are downright scarce and highly sought-after. A few months ago, I introduced you to the basics of Devil Dog patches, providing you with a brief history and insight into the more common pieces. However, I didn’t begin to scratch the surface regarding those items that draw the attention of hardcore collectors and fakers alike.

One could essentially group Marine Corps patches into a few levels of availability or scarcity. I am hesitant to apply the term “rare” as sometimes it erroneously conveys to novice collectors a sense of exorbitant monetary value on an item. What this means is that while something might be hard to find, it doesn’t mean that there are lots of collectors are competing for the same item. However, in some instances with the hard-to-find USMC patches, rare and scarce can be interchangeable and the values can be cost-prohibitive for the majority of collectors. In my experience, I’ve categorized USMC patches by their use (i.e. unit type).

Divisions

These patches cover the WWII USMC divisions ranging from the First (1st) through the Sixth (6th) Marine Divisions (MarDiv). Besides the common patches, there are some hard-to-find examples, especially those created during the very early months of the war. The 1st MarDiv patches that were made in Australia (when the division was relieved and sent to Melbourne for R&R following the Guadalcanal operation of 1942-43). These patches are quite distinct featuring a unique backing material and unique embroidery. Of course there are a vast number of variations for each of the subsequent divisions to be on the lookout for.

- Marine Raider battalion patches are rare enough, but when they are Australian made (like this example), they command a premium when sold (source: USMF).

- 1st US Marine Division with Cape Glouseter tab (source: Snyder’s Treasures).

- One of the popular patch backing materials (for both collectors and moths) is wool as seen on this 2nd Marine Division patch (source: USMF).

- Variations play a significant role in determining value. This heart-shaped variant of the 2nd Marine Division is going to cost a collector a pretty penny (source: USMF).

Marine Air Wing (MAW)

For the purposes of organizing my collection, I have also grouped in the Marine Aircraft Fuselage patches as the units are connected. The MAW units are organized from the 1st through 4th and also include a headquarters group. Each unit has an associated patch design. The same structure applies to the Fuselage units and their patches (1st-4th and HQ). There are several variants of each patch design which can make a novice get cross-eyed wading through each one.

This assortment of patches includes examples of all four Marine Fuselage units along with the HQ patch (shown with the crown). The bottom SSI is from the 1st Marine Air Wing.

Raider Battalions

Perhaps the most widely sought patches originate from the elite Marine Raiders. These legendary units were the original Marine Special Forces units and employed highly skilled grunts who routinely operated behind enemy lines. The unit patch design is simplistic but conveys an ominous symbol superimposed onto a field of blue with five white stars. There are several variations of this patch with correlating price ranges – the upper end of which can break almost any collector’s bank.

- Marine Raider battalion patches are rare enough, but when they are Australian made (like this example), they command a premium when sold (source: USMF).

- This patch is frequently seen for sale online and is continuously attributed to a Marine Raider unit. Unfortunately, no such unit has ever been found to have existed. This patch is something of an anomaly and is more than likely a fantasy piece (source: Snyder’s Treasures).

Amphibious Corps

These patches employ a similar design to the Marine Raiders patch, borrowing the shape, color, five-star arrangement and the central white-bordered, red diamond field.

- This 1st Marine Amphibious Corps patch variant features gold-colored thread for the crossed cannons instead of the more common white thread (source: USMF).

- The half-track-line symbol in this patch is that of the 1st Marine Amphibious Corps – Tank Destroyer unit (source: Snyder’s Treasures).

Marine Defense Battalions

These battalions were responsible for providing protection of bases throughout the Pacific Theater and consisted of more specialized units including coastal gun and anti-aircraft batteries, a detection battery (searchlights and radar) and machine gun units. These patches would be characterized more as scarce rather than rare. Authentic examples are available but are nowhere near as common as the division patches. Expect to pay a bit of a premium for these patches.

- The 18th Defense Battalion SSI design bears more resemblence to that of a Marine Fuselage Wing patch rather than the other Defense Battalion patches (source: Snyder’s Treasures).

- Though quite subtle in design, the 51st Defense Battalion patch easily conveys their mission. This is a rare bullion example (Source: USMF).

- This patch is in keeping with the other designs associated with Marine Defense battalions. This example is from the 52nd Defense Battalion (source: Snyder’s Treasures).

Fleet Marine Forces Pacific (FMFPAC)

Nine patch designs align with the eight units (anti-aircraft artillery, artillery battalions, bomb disposal companies, dog platoons, DUKW companies, engineer battalions, supply and tractor battalions) along with a headquarters unit, and pose an interesting challenge for collectors. Along with the embroidery and backing variations, there are some color alternatives (white emblems instead of gold) which pose some challenges for collectors locating them all.

Showing the patch fronts of four of the Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific; V Amphibious Corps (with the alligator); also displayed is the “Londonderry” patch of the ” Irish Marines’ of the 1st Provisional Marine Battalion.

Among these patches are four examples of the FMF PAC units. The example in the bottom row (with the star) is a more rare white-thread example of the FMF PAC Supply unit. The two patches flanking the FMF PAC Supply SSI are the 5th Amphibious Corps (at left) and Marine Detachment Londonderry patch.

Marine Detachment

These detachment patches are some of the most desirable USMC patches, the Londonderry and Ship’s Detachment patches being a bit more affordable than the more rare (and unique) Iceland patch.

- One of my favorite USMC patch designs is that of the 13th Marine Defense Battalion with the “FMF” superimposed over the seahorse (Source: USMF).

- The 1st Marine Brigade (Iceland) patch is distinct and lacks any of the more common WWII USMC patch traits with its all black field and the polar bear perched upon the ice (Source: USMF).

Aviation Squadrons

Perhaps the most widely sought after and diverse patches stem from USMC aviation squadrons. These patch designs could include variations that range from Disney crafted in painted-leather to embroidered fabric. Each squadron could have many renditions dependent upon how long the squadron was active and based upon where they were located. Squadrons could have their patches made in theater by resident artisans (including squadron personnel) or by domestic manufacturers. Specific designs could vary based upon available materials or leadership changes. As the WWII veterans’ personal artifact groups continue to arrive on the market, collectors still discover new variations of squadron insignia that were previously unknown, making authentication a challenge even for the most experienced patch enthusiast.

- This could be one of the rarest designs of patches for any service branch incorporate bullion thread as seen in this USMC VMD squadron patch (source: USMF).

- Perhaps the pinnicle of USMC aviation squadron patch collecting, the “Blacksheep” of VMF-214 is the most replicated and one of the rarest (source: eBay image).

Education about these patches is key. I cannot emphasize enough that research prior to making any purchases of rare patches is highly recommended. One of the best resources is the U.S. Militaria Forum; specifically, What are the Rarest WWII USMC Patches for detailed insight as shared by the most experienced collectors and militaria historians.

US Marine Corps Uniform: Shoulder Sleeve Insignia Introduction

- The progression of the uniforms of the USMC from 1741 to 1859 (source: USMC)

- Current dress uniforms of the USMC (source: USMC).

As one views any iteration of the current Marine Corps uniform, it will be observed that they are somewhat simple in their design and appointments, paying homage to their traditions and legacy. While the present-day US Marine Corps uniforms may appear to be vastly different from those worn by colonial marines, they carry a significant amount of features and the overall theme from the originals.

- The WWI-vintage SSI of the 11th Marine Regiment of the 5th Marine Brigade (Source: Hayes Otoupalik).

- Here is a pristine example of a WWI Marine uniform with the 11th Marine Regiment, 5TH Marine Brigade patch.

As war waged in Europe in the early twentieth century, the United States was virtually unprepared to take on any combat activities due to the isolationists’ vehement opposition to the seemingly continuous strife of the monarchies of the old countries. The unpreparedness of the US military became apparent as they began to train and outfit the troops. The leadership had to scramble to buy materials to produce the uniforms required to equip nearly 4 million troops.

The Army had been in a period of transition from the uniform patterns used during the Spanish American War, and evolved through a handful of designs prior to arriving at three patterns used during WWI. The Marines, having been even less prepared, had to rely on the the Army for outfitting, for a number of reasons that included unifying all of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (AEF) and the need to consolidate production due to time and resource constraints.

As the AEF began landing in Europe, there was little distinction between the branches of U.S. forces, largely leaving them to all look indistinguishable from each other. The Marines, seeking to set their uniforms apart from those of the Army, began to appoint their jackets with buttons and collar discs while adding the eagle, globe and anchor devices to the overseas cap.

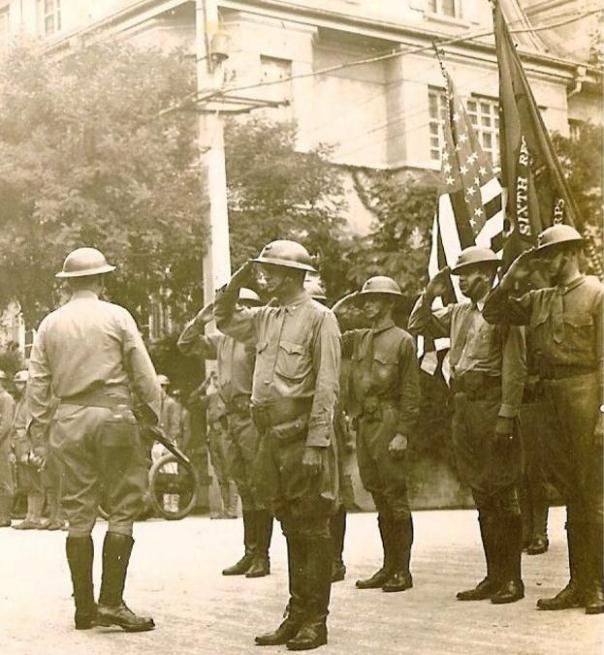

Late in the war, the Marines began applying shoulder sleeve insignia to the left shoulders of their jacket sleeves. With the 6th Marine Regiment being placed under the Army’s 2nd Infantry Division, the design of the Marine SSI bears similarities to the 2ID patch, incorporating the Indian head symbol. The rarer USMC shoulder patch of WWI is that of the 11th Marine Regiment (part of the 5th Marine Brigade) which bears the Roman numeral “V” superimposed over a black EGA. In the years following WWI, the Marine Corps uniforms returned to their original configurations, removing the unit identifiers.

You can clearly see that these interwar-period China Marines lack any SSI (Source: Chinamarine.org).

This Australian-made First Marine Division patch was created for the battle-hardened veterans of Guadalcanal while on R&R in Melbourne Australia (source: Flying Tiger Antiques).

Following combat on Guadalcanal, Marines of the 1st Marine Division were en route to Australia for R&R. It was thought that the Marines would again be wearing army uniforms, like they did during the Great War. Seeking to set the Marines apart from the army troops, discussion among the division leadership began taking place about a solution.

“They sat in facing bucket seats, between the litter of packs, seabags, typewriters, briefcases — the kinds of things that staff officers would necessarily bring out of battle.

General Vandegrift (division commander, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift) had begun to be a little bored with the monotony of the long plane ride. “Twining (then-Lieutenant Colonel Merrill B. Twining),” he said, “what are you doing?”

“An idea I have for a shoulder patch,” said Twining. “The stars are the Southern Cross.”

Vandegrift looked at it for a moment, scribbled something on it, and handed it back to Twining, who saw the word, “Approved,” with the initials, “A.A.V.”

They had been on the ride from Guadalcanal to Brisbane. Because the first few days in Australia were hectic, Twining did nothing else about the patch until one morning he was called into Vandegrift’s office.

“Well, Twining, where’s your patch?” Vandegrift asked to the discomfort of Twining.

“I bought a box of watercolors,” Twining says in recalling the incident, “and turned in with malaria. I made six sketches, each with a different color scheme. In a couple of days I went back to the General with my finished drawings. He studied them only a minute or so and then approved the one that is now the Division patch.” *

- These are the Marine Divisions (1-6). Shown are two versions of the 2nd MarDiv. Three of these patches are wool felt.

- Showing the patch fronts of four of the Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific; V Amphibious Corps (with the alligator); also displayed is the “Londonderry” patch of the ” Irish Marines’ of the 1st Provisional Marine Battalion.

- Marine Air Wing Patch variants. One of these is a felt patch.

- The backs of the patches can help shed light on whether they are authentic.

- Showing the backs of the FMF and other patches.

- Showing the backs of the FMF and other patches.

As the war wore on, other Marine Corps units began to design and implement shoulder sleeve insignia, sourcing from many manufacturers resulting in multiple patch variations for each unit identifier. In March of 1943, Marine Corps leadership made shoulder insignia officially supported, approving them for wear on dress uniforms.

Shortly after the end of the war, the Marine Corps struggled to maintain their existence while their ranks contracted from six divisions and five air wings (and several ancillary battalions) down to three divisions and wings. The need for the shoulder insignia had passed and so they were eliminated on January 1, 1948. No SSI has been (officially) worn on a Marine Corps uniform since that time. As with Army SSI, collecting each version of each unit patch can be a fun yet painfully lengthy process. As with any aspect of collecting, the rarer the patch, the larger the dent will be in your budget.

In preparing to move into collecting USMC SSI, I recommend that you start off simple. Pursue the common patches while keeping your eyes open and setting aside funds for the rarities. It is advisable that you obtain trusted publications to learn how to distinguish between the variants and the faked patches.

Available Resources:

- Complete Guide to United States Marine Corps Medals, badges and Insignia: World War II to Present

- Shoulder Sleeve Insignia of the U.S. Armed Forces 1941-1945

*McMillan, George. The Old Breed : A History of the First Marine Division in World War II. Washington: Zenger Pub. Co, 1979.

A Legacy: Vincennes Wardroom Silver

More than three months into The War, the United States was reeling from suffering substantial and demoralizing losses at Pearl Harbor and again in the Sunda Strait (with the loss of the USS Houston CA-30). The U.S. was in dire need of stopping the bleeding and gaining a moral victory in order to build momentum for what was to become a nearly half-decade long war.

These cased, broken champagne bottles were used to christen the cruisers named for the City of Vincennes, IN. The top bottle helped to name the CA-44 and the bottom, CL-64. Both are preserved at the city’s council chambers archive.

When the keel of the (then, future) USS Vincennes (CA-44) was laid, she was the pride of the small, Southwestern Indiana town of the same name. The citizens embraced her and her future crew, adopting the men who would serve aboard her as their own sons. When she was christened (launched), the daughter (Miss Harriet Virginia Kimmell) of the city’s mayor broke the ceremonial bottle of champagne on her bow, officially naming the heavy cruiser. More than two years later when the ship was commissioned and placed into service (February 24, 1937), the citizens raised funds to purchase and present a gift, a silver tea and coffee service, to the officers of the ship.

With the outbreak of war and the peacetime navy morphing to address the combat needs, USS Vincennes transferred from her home fleet duties within the Atlantic Ocean to augment the Pacific fleet following the losses suffered in the opening days and weeks of the war. As part of readying the ship for service against the Japanese, the Vincennes paid a visit to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, in San Francisco Bay for additional combat upgrades. In conjunction with the changes being made to the ship, the compliment of officers and men was being increased and with space being a premium and the probability of combat engagement with the enemy being almost certain, the silver service and other items were removed from the ship and placed into storage for the duration of the war.

The USS Vincennes’ sterling silver tea and coffee service is on display in the City of Vincennes, Indiana in the council chambers archive.

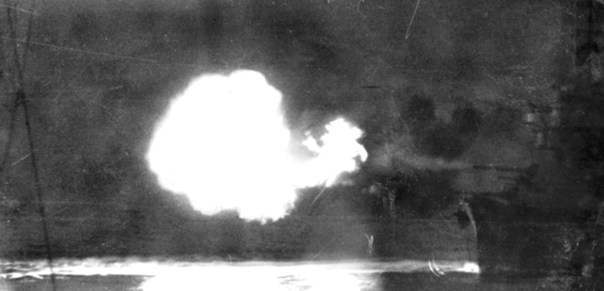

Soon afterward, the Vincennes would take part in some of the most pivotal actions in an effort to stem the Japanese Eastward expansion beginning with the Doolittle Raid, (aiding in the aftermath of) the battle of Coral Sea, the Battle of Midway and the US Marines’ first offensive, Guadalcanal. On the evening of the 2nd night of the landings, the Vincennes would sustain hundreds of Japanese naval gunfire hits and being pierced by the enemy’s Long Lance torpedoes, leaving a blazing, sinking inferno.

The 8″ main battery of the heavy cruiser, USS Vincennes (CA-44) commence firing at enemy positions on Guadalcanal; early morning, August 7, 1942.

Five decades later, the surviving veterans of the lost cruiser would be instrumental in ensuring that the name of their beloved lost ship would be carried to sea aboard a modern cruiser of the Ticonderoga class. At her commissioning in 1985, the city of Vincennes would once again gift the preserved silver service to their newest ship, the USS Vincennes (CG-49) to be used by the officers and visiting dignitaries and guests throughout her twenty-year life.

Upon her decommissioning in 2005, the silver service was returned to the city where it is now displayed and cared for. Perhaps one day, another ship will bear the name Vincennes and the set will serve the officers of a new generation of the adopted sons and daughters of the southwest Indiana city.

Naval Coverings of WWII – Navy Hats

My military collecting focuses almost entirely on documenting my family’s service with both a narrative and visual materials. One of the products of my research will ultimately be a hardbound, four-color book complete with original photographs of these veterans and displays of their uniforms and artifacts. You’ll have to take my word that this is a lengthy undertaking, considering that most of my subjects are long-deceased, requiring interaction with the National Archives and a lot of lag time waiting for the requested service records and materials.

As I began assembling a representative group portraying my uncle’s service in the United States Navy, I soon realized that I would have to collect several uniforms as he went from an Apprentice Seaman to a Chief Warrant Officer during his thirty years of service. For this article, I am going to cover one aspect of the assembled group : headwear.

My uncle enlisted in 1932 and remained on active duty throughout World War II. By 1941, he had advanced to first class petty officer radioman. His specialty was in intelligence and he had been with Joe Rochefort, having attended the Navy’s highly secretive and fledgling cryptologic school in the 1930s. He was meritoriously promoted to chief petty officer (CPO) for his efforts supporting the commander of Task Force 16 during the Battle of Midway. In 1944, he was promoted again to Radio Electrician, Warrant Officer (grade W-1).

Possessing that information, I knew that I had to collect some chief petty officer uniforms as well as some difficult to find warrant officer items. To complete those sets, headgear could pose a significant challenge. I first had to determine what a W-1 (the Navy discontinued this rank at the war’s end) would wear as I had personally never seen the uniform. I referred to some reference material that provided some basic information, but not the specifics regarding all of the hat components for this grade. I could select either (or both) a combination or garrison cap.

With a khaki jacket in my possession and the appropriate epaulettes (shoulder boards) that are affixed to the jacket’s shoulders, I knew that I wanted to have at the very minimum, a garrison cover. Current Chief Warrant Officers’ garrison cover devices include the naval officer’s crest on one side and the rank bar on the opposing side. The rank bar devices did not exist yet during the war (instituted in the 1950s) so I was at a loss for what they wore. I contacted some navy uniform experts who informed me that the W-1 would wear only their specialty devices (in this case, the radioman insignia). During WWII, these devices are mirrored, meaning that they both “point” forward yet look the same from either side. Current devices are not mirrored – Chief Radio Electricians wear two of the same device – one is upside down.

I located a vintage set of the devices and pinned them to the WWII-vintage Navy khaki garrison cap that I had previously obtained. The hat was now complete.

WWII-Era U.S. Navy Radio Electrician Warrant Officer’s Garrison Cap.

I turned my attention to the combination cover (some erroneously call the Navy caps “visor caps”) which is a hat with a visor that may be simply altered to match the uniform by replacing the cover with the appropriate color/material cover. Chiefs and officers could feasibly own a single hat frame (the sweatband/frame/visor) and simply change from white to blue or khaki (also grey or green) to align with the uniform of the day. I wanted to create a combination cap to go with this uniform as it looks classy.

I located a standard officer’s dress blue cover with the wide gold chin strap and the line officer’s crest. I already had a nice example of this cap so I decided that this would be a good base to create the warrant hat. Any alterations I made could easily be reversed to return it to its original state. I also kept the original owner’s name placard in the holder inside the hat. I found an original W-1 hat band and a 24k large hat insignia as well as the unique ½-inch gold chin strap (all vintage components). I disassembled the hat and replaced the appropriate parts with the newly acquired components.

WWII U.S. Navy Warrant Officer’s (W-1) Combination Cover

One last cover I focused on was the CPO hat. Examining numerous period-photographs, I locked onto the hat that I wanted to acquire or assemble. Through the assistance of a friend, I was directed to an early WWII CPO combination cap with a grey cover that was well-enjoyed by a family of moths. The sterling silver hat device was outstanding as was the remainder of the hat. I purchased the hat and obtained a set of covers (blue, white and khaki) to accompany the three CPO uniforms (all chief radioman). Now I could display each chief uniform with using a single combination cover.

World War II-Era U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer Combination Cover.

The remaining uniform left to tackle (for this relative, at least)? A dress blue or white jumper with neckerchief and white hat.